Lunar meteorites

Everything you need to know

What is a meteorite?

A meteorite is a rock that was formed elsewhere in the solar system, was orbiting the sun or a planet for a long time, was eventually captured by Earth’s gravitational field, and fell to Earth as a solid object. A meteoroid is what we call the rock while it is in orbit and before it is decelerated by the Earth’s atmosphere. A meteor is the visible streak of light that occurs as the rock passes through the atmosphere and exterior of the rock is heated to incandescence. Most (99%) recovered meteorites are pieces of asteroids. A few rare meteorites come from the moon (0.7%) or Mars (0.5%).

What is a lunar meteorite?

Lunar meteorites, sometimes called lunaites, are meteorites from Earth’s moon. In other words, they are rocks found on Earth that were ejected from the moon by impacts of asteroidal meteoroids or possibly comets.

How did lunar meteorites get here?

Because the moon has no atmosphere to stop them, meteoroids strike the moon every day. Meteoroids strike the moon at very high velocities, 12-40 km/s (27,000-90,000 mph). Lunar escape velocity averages 2.38 km/s (1.48 miles per second), only a few times the muzzle velocity of a common rifle (0.7-1.0 km/s). Any rock on the lunar surface that is accelerated to lunar escape velocity or greater by the impact of a meteoroid will leave the moon’s gravitational influence. Most rocks ejected from the moon become captured by the gravitational field of either the earth or the sun and go into orbit around those bodies. Over a period of a few years to tens of thousands of years, those orbiting the earth eventually fall to Earth. Those in orbit around the sun may also eventually strike the earth up to a few tens of millions of years after they were launched from the moon.

Words that confuse people

|

How do we know that they are meteorites?

On a broken or sawn face, all lunar meteorites look like some kinds of Earth rocks, even to an experienced meteorite collector or scientist. We can often tell that they came from space, however, because many lunar meteorites have fusion crusts from the melting of the exterior that occurs during their passage through Earth’s atmosphere. On meteorites found in hot deserts, the fusion crusts sometimes have weathered away. As explained in more detail below, however, all meteorites contain certain isotopes (nuclides) that can only be produced by reactions with penetrating cosmic rays while outside Earth’s atmosphere. The presence of cosmogenic nuclides is the ultimate test of whether or not a rock is a meteorite. All lunar meteorites that have been tested show evidence of cosmic-ray exposure.

How many lunar meteorites are there?

At this writing (December 31, 2023), 649 lunar meteorites are recognized. Other rocks that have not yet been classified or described in the scientific literature but which may be lunar meteorites are being sold by reputable dealers. The complication is that some to many of these stones are paired, that is, two or more of the stones are different fragments of a single meteoroid that made the Moon-Earth trip. When confirmed or strongly suspected cases of pairing are considered, the number of actual lunar meteoroids reduces to less than half the number of named stones. Pairing has not yet been established or rejected for the many recently found meteorites, so the actual number is not known with certainty. In the List, known or strongly suspected paired stones are presented on a single line separated by slashes. In most cases, the stones were found close together because a meteoroid broke apart upon encountering the Earth’s atmosphere, hitting the ground or ice, or while traveling within the ice in Antarctica. In the other cases, all from northern Africa, we do not know for sure where the meteorites were found so we cannot establish pairing by find-location proximity. The six LaPaz Icefield stones from Antarctica all have fusion crusts and the broken edges that do not fit together, thus the LAP meteoroid likely broke apart in the atmosphere. They were found on the ice along a linear trend a few kilometers long. Among the ~75 named lunar meteorite stones from Oman, there are 16, each with different names, that all appear to be pieces of a single meteorite.

Pairing and namingAlthough it is confusing, meteorite scientists refer to all found pieces of a landed meteoroid as a single meteorite, ideally with a single name. Thus, Allende refers to hundreds of fragments of a single 2-ton meteoroid that broke apart over Mexico in 1969. All the pieces are paired stones of a fall and they are all called Allende. Thousands of fragments of Sikhote-Alin have been found. With finds (meteorites not observed to fall) different stones are often given different names because they are found at different times by different people. If later studies show two stones to be paired, then one of the names is officially discarded. With the Antarctic and hot-desert meteorites, however, all the stones are originally given different names because so many meteorites are found in a small area. This problem leads to the awkward combination names like Yamato 82192/82193/86032 when one is referring to “the meteorite,” in the accepted sense, as opposed to the individual stones. If the 16 stones of the Dhofar 303 clan of lunar meteorite had been found in the U.S., for example, they would likely all have been given the same name. |

For several reasons we know that the lunar meteorites derive from many different impacts on the moon. The textural and compositional variety spans, and in some ways exceeds, that of rocks collected on the six Apollo landing missions, so the meteorites must come from many locations. More importantly, it is possible to determine how long ago a rock left the Moon using cosmic-ray exposure ages. Small rocks on the surface of the Moon and in orbit around the sun or earth are exposed to cosmic rays. The cosmic rays are so energetic that they cause nuclear reactions in the meteoroids that change one nuclide (isotope) into another. Some of those nuclides produced are radioactive. As soon as they fall to Earth, production stops because the Earth’s atmosphere absorbs nearly all cosmic rays. The cosmic radionuclides in the meteorite decay on Earth with no further production. The most well-known such isotope is 14C (carbon 14), which is produced from oxygen atoms in the meteoroid. Other important radionuclides produced by cosmic-ray exposure are 10Be, 26Al, 36Cl, 39Ar and 41Ca. Because the various radionuclides all have different half-lives it is often possible to tell how long a rock was exposed on or near the surface of the moon, how long it took to travel to Earth, and how long ago it fell. For example, cosmic-ray exposure data for Kalahari 008/009 suggest that the meteorite left the moon at most a few hundred years ago. At the other extreme, Dhofar 025 took 13-20 million years to get here from the moon (Nishiizumi and Caffee, 2001). Because there is a wide range in the Earth-Moon transit times, we know that many impacts on the moon were required to launch all the lunar meteorites.

The lunar meteorites represent fewer impact sites on the moon than the number of meteorites. There are persuasive arguments (cosmic-ray exposure ages, chemical and mineral compositions) that the “YAMM” meteorites found in Antarctica, Yamato 793169, Asuka 881757, MIL 05035, and MET 01210 are source-cratered paired or launch paired, that is, the four meteorites were ejected from the moon as separate rocks by a single impact, the rocks traveled to Earth separately, and that they fell to Earth at different places at different times (Warren, 1994; Arai et al., 2005; Zeigler et al., 2007). [August 2021: Ramlat Fasad 532 from Oman may be another launch pair of the YAMM meteorites.] Other likely cases of launch pairing are (1) the “YQEN” meteorites, Yamato 793274/981031, QUE 94281, EET 87521/96008 (Arai and Warren, 1999, Korotev et al., 2003), NWA 4884 (Korotev et al., 2009), and the NWA 7611 clan (Korotev and Irving, 2021) and (2) the “NNL” meteorites, NWA 032/479, NWA 4734/10597, NWA 8632, and the 6 LAP stones (Zeigler et al., 2005; Korotev and Zeigler, 2014; Korotev and Irving, 2021). Almost certainly, some to many other launch pairings occur among the numerous feldspathic lunar meteorites from hot deserts that have not been studied.

Does it take a big impact to launch a lunar meteoroid?

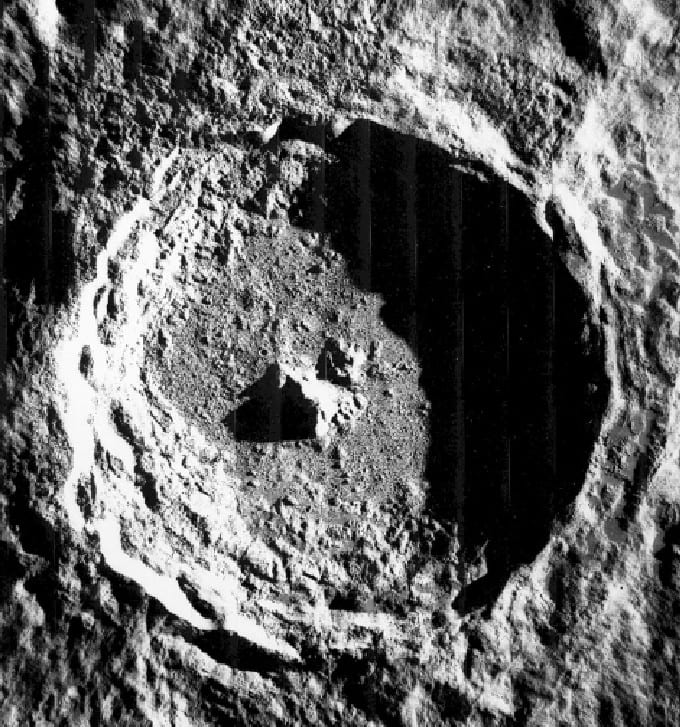

Vogt et al. (1991) estimated that the frequency of impacts on the moon large enough to eject lunar meteorites is greater than 5 per million years. On the basis of impact probability and the known size distribution of lunar craters, Paul Warren (1994) made a persuasive case that lunar meteorites come from relatively small craters — those of only a few kilometers in diameter. The main thrust of his argument is that all the lunar meteorites were blasted off the moon in the last ~20 million years (most in the last few hundred thousand years) and that there have not been enough “big” impacts on the moon in that time to account for all the different lunar meteorites. As new lunar meteorites are found each year, Warren’s argument becomes more valid. James Head (2001) calculates on a theoretical basis that impacts causing craters as small as 450 m (about a quarter of a mile) in diameter can launch lunar meteorites.

More recently, Basilevsky et al. (2010) argue on the basis of the known number of lunar meteorites and the frequency of impacts on the moon that “a significant part of the lunar meteorite source craters are not larger than a few hundreds of meters in diameter.” (That is big if it happens in your backyard, but it is not so big for the whole moon.) If lunar meteorites come from such small craters, it is especially difficult to locate the actual source crater of any particular lunar meteorite.

Vladimir Shuvalov and Natalia Artemieva of the Institute for Dynamics of Geospheres in Moscow reach the following conclusion on the basis of numerical impact modeling: “An interesting consequence may be connected with 83-km-diameter crater Tycho. ~100 Myr ago [the terrestrial Cretaceous Period], the crater was created by 6-7 km-diameter projectile in an oblique (30-45°) impact. This impact event delivered 25–100 km3 of lunar material to the Earth, i.e., our planet was uniformly covered by ‘Tycho’ meteorites with average density 0.1-0.3 kg/m2 (assuming 30% losses in the atmosphere). These massive deposits may be found in proper stratigraphic layers similar to the Ordovician meteorites.”

Prediction 19 years before the first lunar meteorite was recognized“The occurrence of secondary craters in the rays extending as much as 500 km from some large craters on the moon shows that fragments of considerable size are ejected at speeds nearly half the escape velocity from the moon (2.4 km/sec). At least a small amount of material from the lunar surface and perhaps as much or more than the impacting mass is probably ejected at speeds exceeding the escape velocity by impacting objects moving in asteroidal orbits. Some small part of this material may follow direct trajectories to the earth, some will go into orbit around the earth, and the rest will go into independent orbit around the sun. Much of it is probably ultimately swept up by earth.”… “There is also a possibility that fragments can be ejected at escape velocity from Mars by asteroidal impact, though not as large a fraction as is ejected from the moon. If some small amount of material escapes from Mars from time to time, it seems likely that at least some small fraction of this material would ultimately collide with earth.” Shoemaker E. M., Hackman R. J., and Eggleton R. E. (1963) Interplanetary correlation of geologic time. Advances in Astronautical Sciences, vol. 8, p. 70-89. |

Where on the moon do they come from? Are any from the far side of the moon?

Although scientists like to speculate that a certain lunar meteorite came from a certain crater or region of the moon, no one has identified with certainty the source crater from which any of the lunar meteorites originated.

There is some evidence and model results indicating that asteroidal meteoroids strike the western (leading) hemisphere of the moon (that is, the “side” with Mare Orientale, which means east because astronomical telescopes see the moon upside down!) a bit more frequently than the eastern hemisphere (the Mare Marginis “side”). On the other hand, lunar meteoroids leaving the eastern hemisphere may have a slightly better chance of reaching Earth. Overall, however, there is probably little east-west bias in our lunar meteorite collection. There are reasons to expect that asteroidal meteoroids strike the equatorial areas of the moon a bit (1.28 times) more frequently that the polar regions.

There are no reasons to suspect that lunar meteorites come from the nearside of the moon more frequently than the farside, or vice versa. So, half of the lunar meteorites come from the far side of the moon. It is that simple. We just do not know for certain which ones those are. There is no scientific basis for a statement in an advertisement on ebay: “The ONLY LUNAR meteorite from the dark side of the moon.” (Also, of course, the “dark side” of the moon keeps changing with lunar phase! Except for some locations at the poles, any place in the dark will be sunlit 14 days later.)

Some great technical reading: Gladman et al. (1995), Le Feuvre and Wieczorek (2008), and Gallant et al. (2009).

For any given lunar meteorite, the probability is not exactly 50-50 that it came from either the near side or the far side. There is more mare basalt on the near side than the far side (FeO map; Fig. 18), so the chance is better than 50-50 that an iron-rich meteorite (mare basalt or basaltic breccia) is from the near side and that an iron-poor meteorite (feldspathic) is from the far side. As explained below, Sayh al Uhaymir 169, Dhofar 1442, Northwest Africa 4472/4485 and Northwest Africa 6687 must derive from the near side because of their high concentrations of thorium.

How big are lunar meteorites?

The largest single stone appears to be Northwest Africa 12760 at 58.1 kg (128 lbs.). This stone is one of many of the NWA 8046 clan (paired meteorite stones) of which there is more than 200 kg. At the other extreme, several of the lunar meteorite fragments found in Antarctica and Oman only weigh a few grams (a U.S. nickel coin weighs 5 grams). The smallest named stones are Graves Nunataks 06157 at 0.788 g and Dar al Gani 1048 at 0.801 grams. The largest meteorite is NWA 12691, which consists of “many” pieces totaling 104 kg in mass.

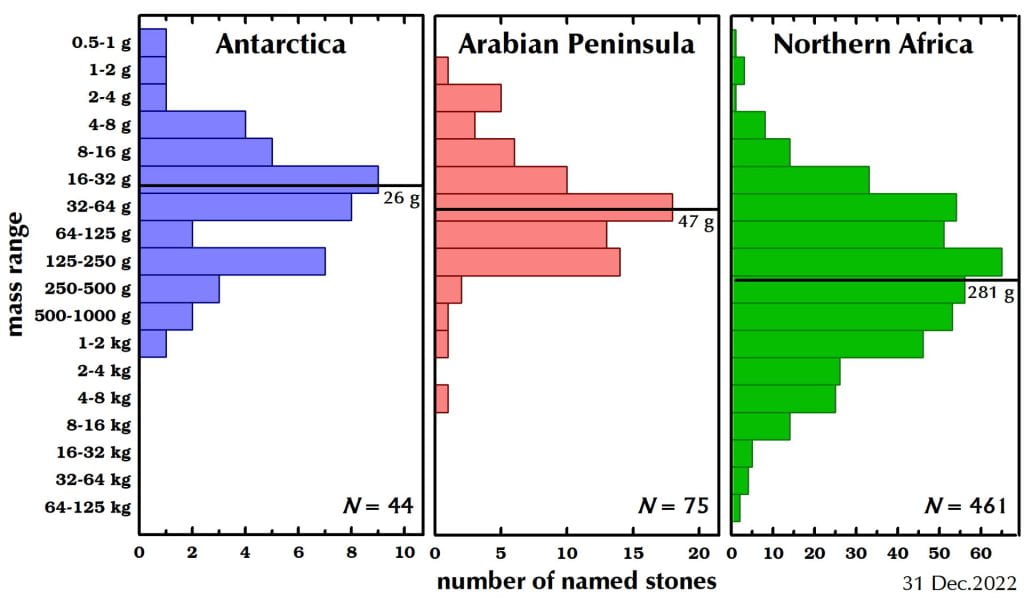

Mass distributions for lunar meteorites are presented in Fig. 6. For at least 2 reasons, however, the figure is misleading.

1) From Antarctica, for example, the 7 Dominion Range meteorites and the 6 LaPaz Icefield meteorites are each pairs (pieces) of a single meteoroid that made the Moon-Earth trip. The 44 lunar meteorites from Antarctica represent about 23 meteoroids and the 76 from the Arabian Peninsula represent about 31 meteoroids (Korotev and Irving, 2021), when likely pairings are considered.

2) Pairing relationships are not well established among the NWA (Northwest Africa) meteorites. In some cases, a pile of many rocks has been given a single name (e.g., NWA 12691) whereas in others (most notably the 40+ named stones of the NWA 8046 clan) different rocks from a single fragmented meteoroid are given separate names, as for the Antarctic meteorites. The 281 northern Africa lunar meteorite stones for which there are compositional data probably represent 77-99 different meteoroids (Korotev and Irving, 2021). More generally, it is possible to likely that several named, low-mass (e.g., <20 g) lunar meteorites from northwestern Africa, particularly those purchased after 2020 (NWA numbers >13000), are fragments purchased by collectors for a few hundred dollars from a dealer with a box of paired, look-alike fragments from a single meteorite. The collector then has the stone classified because a meteorite with a name can be resold for more money than one without a name. Other collectors may buy other stones from the same box and, if classified, the stones receive different names.

Regardless of these complications, it is clear that lunar meteorites from Antarctica and the Arabian Peninsula are about the same size whereas, for some reason unknown, those from northern Africa are considerably larger.

How rare are lunar meteorites?

Meteorites are very rare rocks; lunar meteorites are exceedingly rare. It difficult to assess how rare they really are. Of the ~44,000 named meteorite stones found in Antarctica (1976-2018), where record keeping has been superb, 0.10% (1 in 1000) meteorite stones is from the moon (44 stones representing 23-24 meteorites); for martian meteorites, it is 0.07%. The numbers are significantly greater for northern Africa, 3.2% lunar and 1.9% martian. The greater proportions for the Sahara Desert are largely an artifact of nonrandom sampling and naming – not all ordinary chondrites found in northern Africa are classified and named and, for reasons discussed above, different stones from a single lunar meteorite fall are given individual names artificially exaggerating the count.

Another measure of rarity is mass. The total mass of all known lunar meteorites is about 1159 kg (2555 lbs., Table 1). By comparison, the total mass of all stony meteorites is more than 92,000 kg., so lunar meteorites account for 1.3% of the mass.

The mass of all known lunar meteorites is now (December 31, 2023) about 4.4 times the mass of the rocks >1 cm in size collected on the Apollo missions.

Lunar meteorites for saleMeteorites, including lunar and martian meteorites, are easily available for purchase. Samples (whole stones, end cuts, slices, chips, crumbs, dust) of lunar meteorites sell or have sold on the internet for between $20 per gram (Bechar 003 clan) and $4,000 per gram, depending upon rarity (perceived or real!) and demand. By comparison, the price of 24-carat gold is about $60/gram and gem-quality diamonds start at $1000-2000/gram. Prices of lunar meteorites have declined with time as the number of meteorites has increased.Many rocks advertised on the Internet as lunar meteorites are, in fact, meteorites from the moon sold by reputable dealers. Some are not, however. On some buy-sell sites, there are more lunar meteorwrongs for sale than lunar meteorites. I have been contacted by eight men who have wanted to buy a lunar meteorite to mount in a piece of jewelry for their girlfriend, fiancée, or wife. Be aware that compared to gemstones, lunar meteorites are not “hard” rocks and most have fractures from meteorite impacts on the moon. Unless well mounted, they might fracture and break. Although I love lunar meteorites, they are not all that attractive compared to gemstones. Get her a diamond, emerald, opal, or agate! |

Where, how, and when are they found?

In the lingo of meteoritics, all lunar meteorites have been finds; none are falls. In other words, no lunar meteorite has yet been observed as a meteor and then found on the ground. This is a curious fact as there are fewer martian meteorites than lunar meteorites yet several of the martian meteorites were observed to fall (Chassigny, Shergotty, Nakhla, Tissint, Zagami). This is not my area of expertise but I speculate that meteoroids from the moon are not travelling as fast as meteoroids from asteroid belts or Mars when they encounter Earth’s atmosphere so maybe lunar meteors are not as bright as asteroidal meteors.

No lunar meteorite has yet been found in North America, South America, or Europe. We can reasonably assume that lunar meteorites have fallen on these continents in the past 100,000 years, but if someone has found one, it is not yet been recognized as a lunar meteorite.

Nearly all lunar meteorites have been found in areas that are well known to be good places to find meteorites. All such places are dry deserts where there are geologic mechanisms for concentrating meteorites, where rocks of terrestrial origin are rare, and where meteorites do not weather away quickly from exposure to water.

Most lunar meteorites have been found in the Sahara Desert of northern Africa and in the desert of Oman – all since 1997. Antarctica is also a desert in that the precipitation rate is very low. Meteorites from hot deserts are almost exclusively found by local people or experienced meteorite hunters.

Allan Hills 81005 (ALHA 81005), the first meteorite to be recognized as originating from the moon, was found during the 1981-82 ANSMET collection season on January 18, 1982. The three Yamato 79xxx meteorites were collected earlier, but not recognized to be of lunar origin until 1984. The first lunar meteorite to be found appears to be Yamato 791197, on 20 November 1979. However, it is not known when Calcalong Creek (Australia) was found. The Meteoritical Bulletin states “after 1960,” but it was not recognized to be of lunar origin until 1990, so it may well have been collected earlier than Yamato 791197.

Shişr 166 was found at night with a flashlight. Oued Awlitis 001 was found embedded in roots of a dead tree during a search for firewood.

How are lunar meteorites recognized and identified?

Our lunar meteorites are the products of a series of events, some of which are improbable: An asteroid impacts the moon, a lunar rock is accelerated to escape velocity, the rock eventually lands on Earth, someone finds it, and someone recognizes that is is from the moon. It is the last two events that are the most improbable.

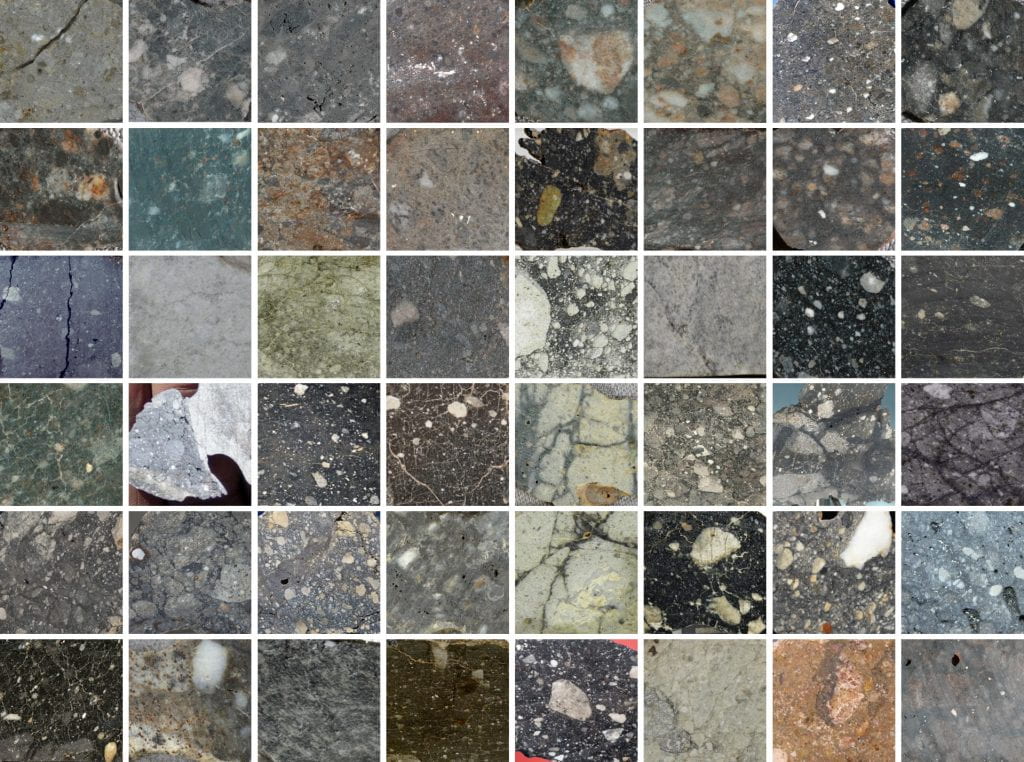

Although the discovery that there are rocks on Earth that originated from the moon is relatively new, lunar rocks have surely been dropping from the sky throughout geologic history. Mikhail Nazarov and colleagues of the Vernadsky Institute in Moscow estimate that “several tens or few hundred kilograms” of lunar rocks in the mass range of 10-1000 g strike the Earth’s surface every year. That fact does not make lunar meteorites easy to find or recognize, however. Under ideal conditions, e.g., Antarctica, some lunar meteorites are almost instantly recognizable as lunaites because they have fusion crusts that are vesicular. No Earth rock and no other kind of meteorite has a crust that is as vesicular as that of lunar meteorites QUE 93069, PCA 02007, or Calcalong Creek. Some lunar meteorites (the basalts) do not have such vesicular fusion crusts, however, and the fusion crust of most lunar meteorites found in hot deserts has been ablated away by wind-blown sand. In the absence of a fusion crust, a lunar (or martian) meteorite is less likely to be recognized as a meteorite than is an asteroidal meteorite because it more closely resembles terrestrial rocks in mineralogy. A weathered lunar meteorite would not be an impressive or suspicious looking rock if found in a cornfield or a parking lot. A brecciated lunar meteorite could easily be overlooked as a terrestrial sedimentary or volcaniclastic rock. Even experienced meteorite collectors admit that Kalahari 009 does not “look like” any kind of meteorite. Lunar meteorites contain a much smaller amount of metal than ordinary chondrites, so most are not attracted to a magnet. Also, they have densities similar to terrestrial rocks; they are not heavy for their size, as are most meteorites. Although I had been studying Apollo lunar rocks for 18 years, I did not recognize the MAC88105 lunar meteorite as a moon rock when another member of the 1988 ANSMET team handed it to me in the field and asked, “What do you think about this one?” Unfortunately, lunar meteorites and some kinds of Earth rocks strongly resemble each other in hand specimen.

Bottom line: Even for an expert it is not usually possible to identify a lunar meteorite just “by looking.” Only expensive and time-consuming tests can prove that a rock is a lunar (or martian) meteorite. “Looks like” is not a good test for lunar meteorites. People have sent me photos of broken concrete that they claim “looks like” some of the photos of lunar meteorites on my website.

How are they named?

By long-standing convention, meteorites are named after the location where they are found. Calcalong Creek is a place in Australia, for example. Somewhat contrary to the convention, the Antarctic meteorites often go by abbreviated names, where ALHA = Allan Hills, DEW = Mount DeWitt, DOM = Dominion Range, EET = Elephant Moraine, GRA = Graves Nunataks, LAP = LaPaz Icefield, LAR = Larkman Nunatak, MAC = MacAlpine Hills, MET = Meteorite Hills, MIL = Miller Range, PCA = Pecora Escarpment, and QUE = Queen Alexandra Range. Similarly, the Dar al Gani (Libya), Northeast Africa, Northwest Africa, and Sayh al Uhaymir meteorites are sometimes abbreviated DaG, NEA, NWA, and SaU. Because hundreds to thousands of meteorites have been found in Antarctica and hot deserts, serial numbers are used in addition to names. For the Antarctic meteorites, the first two digits of the numeric part of the name represents the collection year.

What is the difference between a lunar meteorite and a tektite?

A lunar meteorite is a rock from the moon. A tektite is not a meteorite (it never orbited the sun or Earth) and it is not from the moon. A tektite was formed from Earth material during the impact of a meteoroid.

How are lunar meteorites classified?

Lunar rocks are classified by the minerals they contain (mineralogy), how the mineral grains are put together (texture), how the rock formed (petrology), and chemical composition (chemistry). These different parameters sometimes cause confusion because a geochemist might call a given rock “feldspathic” (dominant mineral) or “aluminum rich” (chemical composition) while a petrologist might call the same rock an “anorthosite” (mineral proportions and implied mode of formation) or “regolith breccia” (texture and type of rock components).

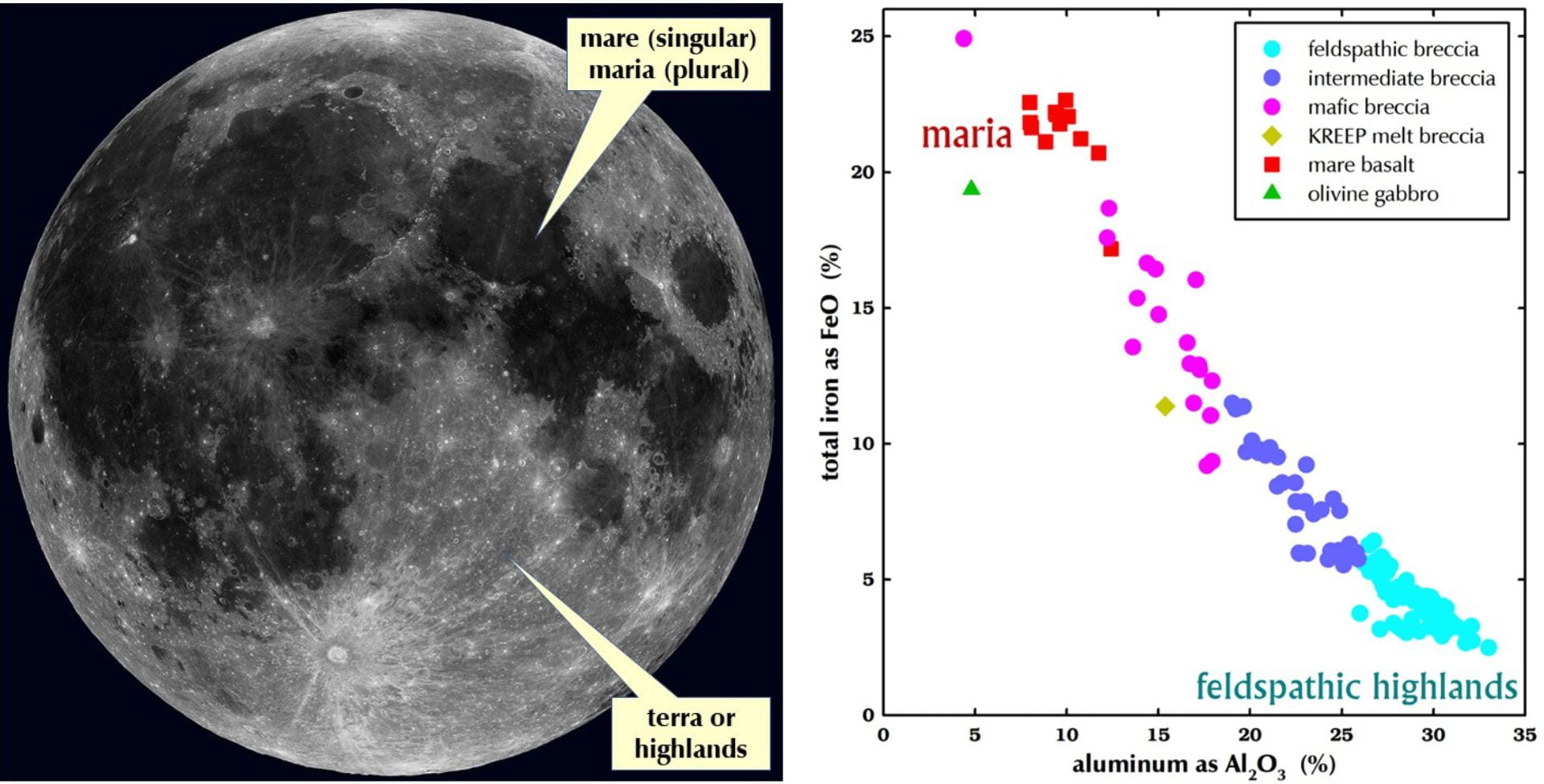

Since the time of Galileo, the lunar surface has been divided into two types of terrane, the mare (pronounced mar’-ay, which is the Latin word for sea) and the terra (land) or highlands.

Rocks from the maria are classified as basalts because they are crystalline, igneous rocks (texture) consisting mainly of pyroxene and plagioclase (mineralogy). Specifically, they are called mare basalts because they formed when magmas from inside the moon erupted (petrology) into the basins formed by the impacts of small asteroids early in lunar history to form the maria. Mare basalts are subclassified by chemical composition (chemistry), for example, “low-titanium (Ti) mare basalt.” Mare basalts are rich in iron because they contain pyroxene, olivine, and ilmenite, all of which are iron-rich minerals, and the amount of pyroxene + olivine + ilmenite exceeds the amount of iron-poor plagioclase.

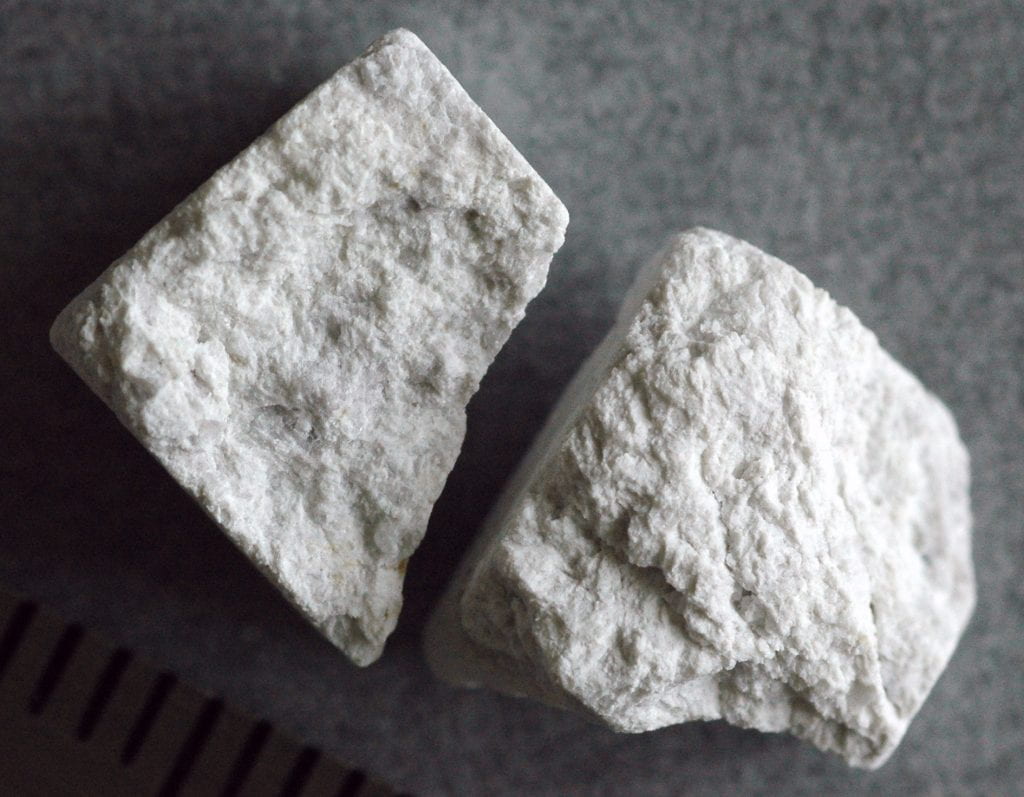

Feldspars are some of the most common minerals of the crust of the earth and moon. Rocks of the lunar highlands contain a high proportion (60-99%) of a type of feldspar known as plagioclase. In particular, the plagioclase of the lunar highlands is the calcium-rich variety known as anorthite (the more sodium-rich varieties of plagioclases are rare on the moon). Mineralogically, a rock composed mostly of the anorthite is called an anorthosite, and most rocks of the lunar highlands are, in fact, anorthosites. Lunar scientists often refer to the highlands crust as “feldspathic,” indicating the major mineral, or “anorthositic,” indicating the major rock type. Anorthite, like all forms of feldspar, is rich in aluminum and poor iron.

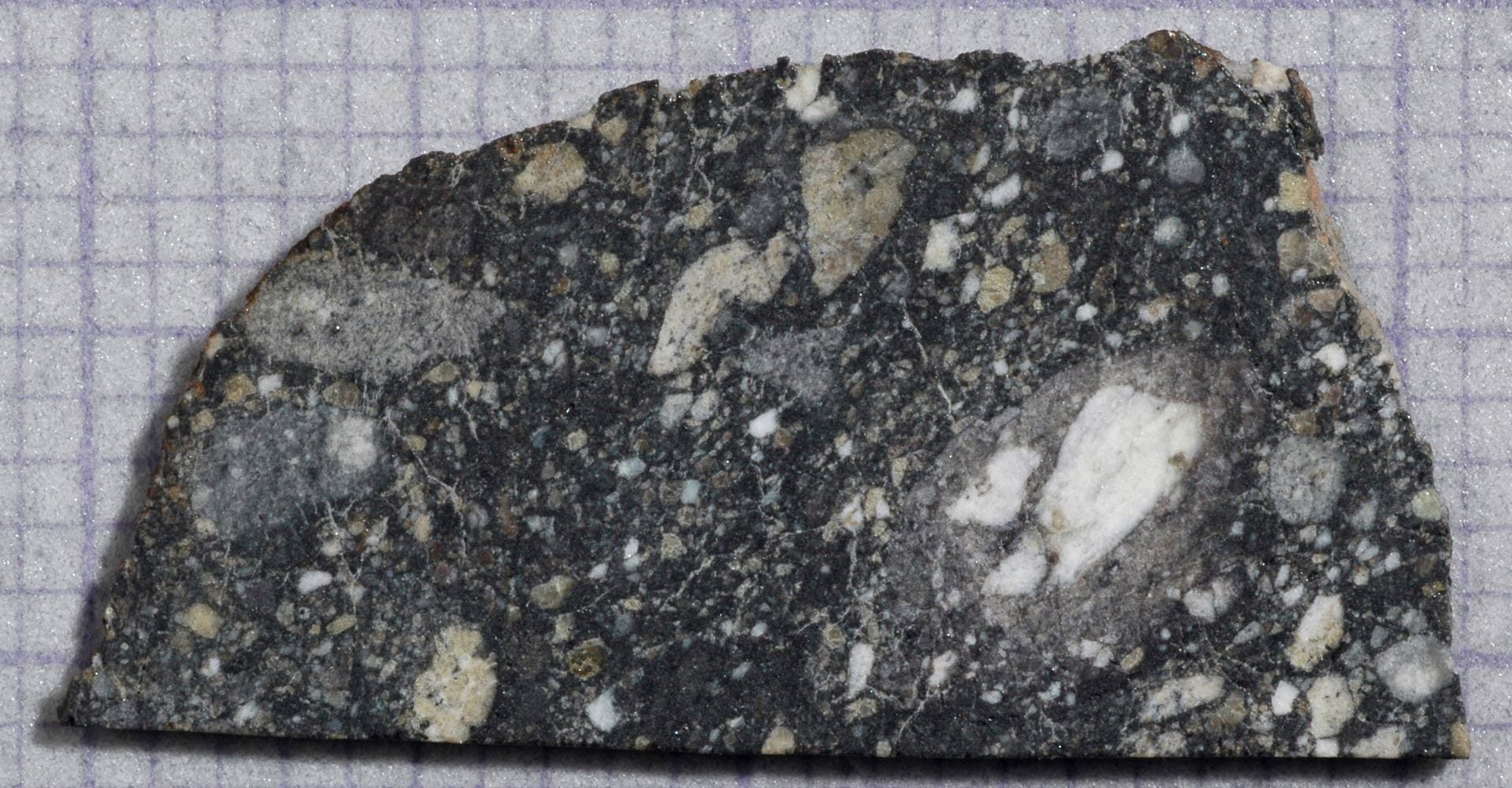

Impact breccias

The early igneous crust of the moon was composed largely of anorthosite. Igneous anorthosite rocks are rare at the surface of the lunar highlands now, however, but some were found on the Apollo missions. Over 4.5 billion years impacts of asteroidal meteorites on the moon have both broken rocks of the lunar crust apart and glued them back together many times. Consequently, all lunar meteorites from the highlands are anorthositic breccias (pronounced brech’-chee-uz), a textural term for a rock that is composed of fragments of other rocks and that is held together by shock compaction or by material that was partially or totally molten.

Monomict breccia is a term applied to a breccia that is made up entirely of one kind of rock. Monomict breccias are rare on the moon because meteoroid impacts tend to mix different kinds of rocks together. Northwest Africa 5000 has been called a monomict breccia because all the large clasts appear to be the same rock type.

Dimict breccias or dilithologic breccias are made up of only two lithologies. The term is usually applied to a common type of rock collected from the Apollo 16 mission that consists of anorthosite (light color) and mafic (dark, iron rich) crystallized impact melt in a mutually intrusive textural relationship. Among lunar meteorites, SaU 169 and NWA 7022 can be regarded as a dilithologic breccias.

The lunar surface is covered with fine-grained material called soil or regolith. The shock wave associated with an impact can lithify the regolith – it can turn the fine, powdery material into a coherent rock called a regolith breccia. At depth, coarser fragments can be lithified to form a fragmental breccia. Breccia is a textural term that applies to rocks of both the maria and highlands. Many lunar meteorites are feldspathic regolith breccias, that is, rocks consisting of lithified soil from the lunar highlands.

Polymict breccia is a general term that encompasses all breccias that are neither monomict or dimict (poly = many, mict = mixture). Types of polymict breccias are glassy melt breccias, crystalline impact-melt breccias, granulitic breccias, regolith breccias, and fragmental breccias. Each of these breccia types has a different texture because the set of conditions that formed them differed.

A large impact can melt rock, forming impact melt. The melt usually collects rock fragments called clasts as it is forced away from the point of impact within a crater. When the melt cools, it forms an impact-melt breccia – clasts suspended in a matrix of solidified (glass or crystalline) impact melt. An impact-melt breccia can be regarded as in igneous rock because it formed from the cooling of a melt. Regolith and fragmental breccias are the closest lunar equivalents to terrestrial sedimentary rocks. Granulitic breccias are metamorphic rocks in that they were originally some other type of breccia that was metamorphosed (recrystallized) by the heat of an impact. Clasts are often not obvious in sawn pieces of granulitic breccias (e.g., NWA 3163 clan).

Textural differences among the various breccias types are often subtle. Many different petrologists have classified lunar meteorites and they have not been mutually consistent in application of the textural terms. In part the inconsistency results from the petrographic thin- or thick-sections used to classify a meteorite being small in area, sometime less than 1 cm2, compared to those used to classify terrestrial rocks. Clasts in lunar meteorites are frequently larger than a centimeter in size (see the NWA 773 clan). One petrologist may call a lunar meteorite an impact-melt breccia while another may identify it as a fragmental breccia because they are looking at “different parts of the elephant.” Thus, differences in classified breccia type do not provide strong evidence that two meteorites are not paired.

Some kinds of terrestrial rocks that are not impact breccias strongly resemble lunar impact breccias.

The concentration of iron or aluminum serves as a useful chemical classification system in lunar rocks. Lunar meteorites that are mare basalts (e.g., NWA 032) or breccias composed mainly of mare material (EET 87521/96008) are poor in aluminum and rich in iron. In contrast, meteorites from the feldspathic highlands are rich in aluminum and poor in iron. Glass spherules and basalt fragments from the maria have been found as clasts in most of the highlands meteorites and some (e.g., Yamato 791197) contain a higher proportion of mare material than others. Such meteorites plot on the high-iron end of the range of highlands (feldspathic) lunar meteorites in Fig. 16. Some intermediate lunar meteorites (e.g., QUE 94281) apparently derive from places where the mare and the highlands are in close proximity because they are breccias consisting of clasts of both mare and highlands rocks. (All regolith samples from the Apollo 15 and 17 missions are mixed in this way.) Such meteorites have intermediate concentrations of iron and aluminum. We might expect, as more lunar meteorites are found, that the gaps in the aluminum-iron plot above will be filled in.

Why are lunar meteorites important?

It may seem, considering that 382 kg of well-documented rock and soil samples were obtained from nine locations by the Apollo and Luna missions, that rocks from unknown points on the lunar surface cannot be very important. For several reasons, however, the lunar meteorites have provided new and useful information.

The Apollo missions all landed in a small area on the lunar nearside, and some of those missions were deliberately sent to sites known to be geologically “interesting,” but atypical of the moon. (On Earth, Yellowstone National Park is geologically “interesting,” but hardly typical.) The gamma-ray and neutron spectrometers on the Lunar Prospector mission (1998-1999) have shown that all of the Apollo sites were in or near a unique and anomalously radioactive “hot spot” on the lunar nearside in the vicinity of Mare Imbrium. This existence of this hot spot, sometimes known as the Procellarum KREEP Terrane or PKT, indicates that the mare-highlands distinction of the ancient astronomers is not adequate in a geochemical sense. Many rocks collected on the Apollo missions that likely originated from the PKT (especially those from Apollos 12, 14, and 15) are neither mare basalts nor feldspathic breccias. They are rocks (usually impact-melt breccias) of intermediate FeO concentration (~10%) with high concentrations of the naturally occurring radioactive elements: K (potassium), Th (thorium), and U (uranium). Such rocks are often called “KREEP” because, in addition to K, they have high concentrations of other elements that geochemists call incompatible elements such as the rare-earth elements (REE, like lanthanum and cerium) and phosphorus (P). Lunar meteorite Sayh al Uhaymir 169 with a whopping 30 ppm Th is a “KREEPy” meteorite. Almost certainly, it derives from the PKT. Other meteorites that have high concentrations of Th, like Dhofar 1442, Northwest Africa 4472/4485, and Northwest Africa 6687, also likely originated in or near the PKT. Most of the rest of the lunar meteorites appear to have come from outside the PKT because they have low concentrations, typically <1 ppm, of Th. This distribution is reasonable in that we believe that the lunar meteorites are rocks from near randomly distributed locations on the lunar surface, and most locations on the lunar surface are not high in radioactivity.

The map of Fig. 17 shows the distribution of the concentration of thorium (Th, in parts per million), a naturally occurring radioactive element, on the lunar surface as determined by the gamma-ray spectrometer on Lunar Prospector, which orbited the moon in 1998 and 1999 (Lawrence et al., 2000; Gillis et al., 2004). Most lunar meteorites have low Th concentrations but a few have high concentrations (see last column of the List). The figure shows that (1) the Apollo missions all landed in or near a region of the moon with anomalously high radioactivity (the anomaly, which we call the Procellarum KREEP Terrane was not known at the time of Apollo site selection) and (2) most of the lunar meteorites must come from areas of the moon that are distant from the PKT because most have low Th. Thus, one of the values of the lunar meteorites is that they are samples from places on the moon that are more typical of the lunar surface (low radioactivity) than the Apollo samples.

Also, most of the lunar meteorites are breccias composed of fine material from near the surface of the moon. This fine-grained material has been mixed by many impacts. As a consequence, the composition and mineralogy of a brecciated lunar meteorite is likely to be more representative of the region from which it came than any single unbrecciated (igneous) rock from the same region.

We know that over much of the moon, and most of the far side, the material of the lunar surface has only 3-6% FeO because it is highly feldspathic.

About half of the lunar meteorites have 3-6% FeO, thus these meteorites are entirely consistent with derivation from typical feldspathic highlands.

These various factors lead to the ironic circumstance that the feldspathic lunar meteorites together provide us with a better estimate of the composition and mineralogy of the typical highlands surface than we were able to obtain from the Apollo samples.

The lunar meteorites have also provided us with crystalline mare basalts that are different from any collected on the Apollo and Russian Luna missions. In particular, the basalts of the Northwest Africa 773 clan are different from any rocks in the Apollo collection (e.g., Jolliff et al., 2003; Valencia et al., 2019) as are the anorthositic troctolites of the NWA 5744 clan (Gross et al., 2020; Korotev and Irving, 2021).

Anagrams for lunar meteorite

literature omen | relearn timeout | marine roulette | numerator elite | tourmaline tree |