Earth rocks that look like planetary impact breccias but are not

Most breccias and breccia-like rocks found on Earth were formed on Earth - They are not meteorites

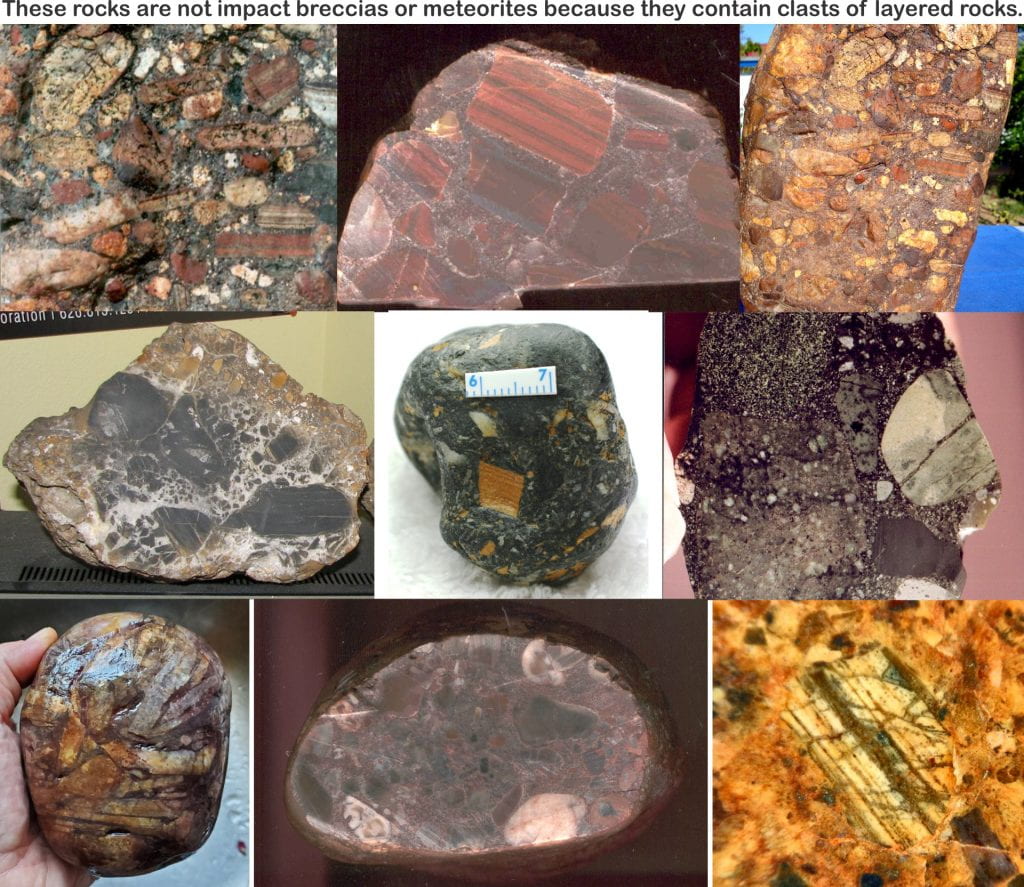

Most lunar and some other types of meteorites are breccias – rocks made from fragments of older rocks that have been broken apart and glued back together by impacts on the parent body (asteroid, Moon) of older meteorites. The fragments are called clasts. Impact breccias typically contain both small mineral clasts and larger lithic clasts, that is, fragments of rock consisting of several to many mineral grains.

Breccias occur on Earth, too, and some rare ones were produced by the impact of meteorites. Most terrestrial breccias, as well as rocks that are not breccias but look like breccias, were produced by other processes such as faulting, sedimentation, and volcanism. The photos in the mosaics below were sent to me by persons who wanted to know if the rocks were meteorites. None of the rocks have self-evident fusion crusts, so I think, but do not know for certain, that all the rocks are terrestrial. Many are sedimentary rocks. Several are pyroclastic (volcaniclastic) rocks or porphyritic basalts. I have been sent photos of breccia-like “rocks” that I am rather certain were just broken pieces of concrete.

Some characteristics to look for

Not reddish

On the Moon and asteroids, rocks are not colorful; they are never dark red and the clasts are not reddish. The matrix is not reddish. A few lunar meteorites, most notably the Dhofar 303 clan, have been stained pinkish with terrestrial hematite, but the staining is “patchy” and not at all systematic. If it is reddish, then it is not a meteorite breccia.

Polymict

Nearly all brecciated lunar rocks are polymict breccias – mixtures (-mict) of many different kinds of rocks (poly-). In the rocks of the next three mosaics, the clasts all seem to be of the same kind of rock, i.e., the rocks are not polymict. Impact breccias dominated by a single type of clast – a monomict breccia – do occur among meteorites, but they are rare. Among lunar meteorites, Northwest Africa 5000 has been identified (not entirely accurately) as a monomict breccia and some eucrites and diogenites are effectively monomict breccias.

No rims

Clasts in meteorites rarely have rims, whereas rims are common in some type of terrestrial breccia look-alikes.

No quartz, no layers

Quartz does not occur as clasts in meteorites but is a common clast type in terrestrial sedimentary rocks. Clasts of layered sedimentary rocks do not occur in meteorites although such rocks occur on the surface of Mars and one might be found on Earth as a meteorite someday.

No rounded clasts

On Earth, rounded clasts are common because rock fragments become rounded by abrasion against other fragments in moving water. Impacts on the Moon and asteroid produce angular fragments and there is no moving water to round them. If a breccia-like rock contains numerous rounded rock fragments, then it is not a meteorite.

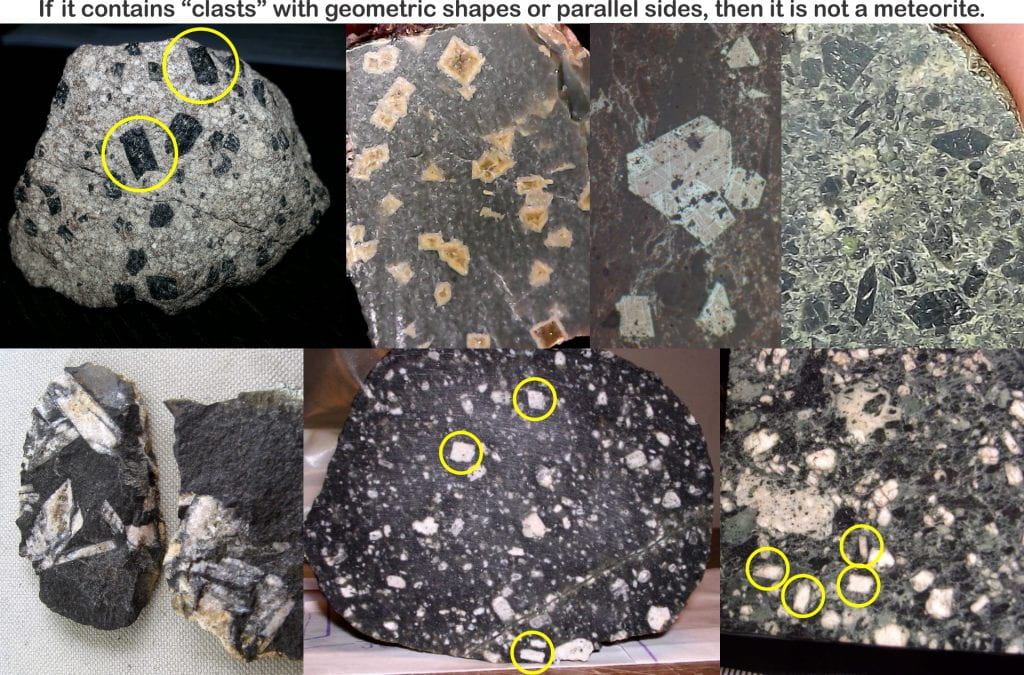

No geometric shapes

Geometric shaped “clasts” can only form from crystallization of a mineral from a melt. Such a rock is an igneous rock, not a breccia, and the “clast” is properly called a phenocryst. Not all phenocrysts have geometric shapes, however.

No “clasts” with high aspect ratios

Fracturing of rock by meteorite impacts only rarely leads to fragments with aspect ratios (length/width) greater than 3/1. Long-thin clasts and phenocrysts do occur in terrestrial rocks, however.

No preferred orientation

Because of the low gravity and lack of water on the Moon and asteroids, clasts in breccias from these planetary bodies rarely display preferred orientation.

Impact breccias are fractal

Impact breccias are fractal objects – they look the same regardless of the scale at which you look at them. The clasts have a large range in size. On the left, below, is a photograph of a sawn face of lunar meteorite NWA 5000, about 12 cm high and 8 cm wide. In the middle is an enlarged image of the portion within the yellow rectangle on the left. Similarly, on the right is an enlargement of the area within the yellow rectangle of the middle. This fractal characteristic is important because in some terrestrial sedimentary rocks clasts sizes have been sorted so that they are all about the same size. Impact breccias have a large range of clast sizes.

Pebble conglomerates

One type of sedimentary rock that is sometimes mistaken for a meteorite is a pebble conglomerate. Such rocks usually start as deposits of rounded pebbles and fine grained silt and clay. The pebbles in pebble conglomerates are rounded – a sure sign that it is not an impact breccia.

Porphyritic volcanic rocks are not breccias

Porphyritic volcanic rocks have large crystals called phenocrysts (not clasts) in a fine-grained crystalline matrix. The phenocrysts are sometimes acicular (needle shaped) and often have geometric shapes like rectangles or trapezoids.

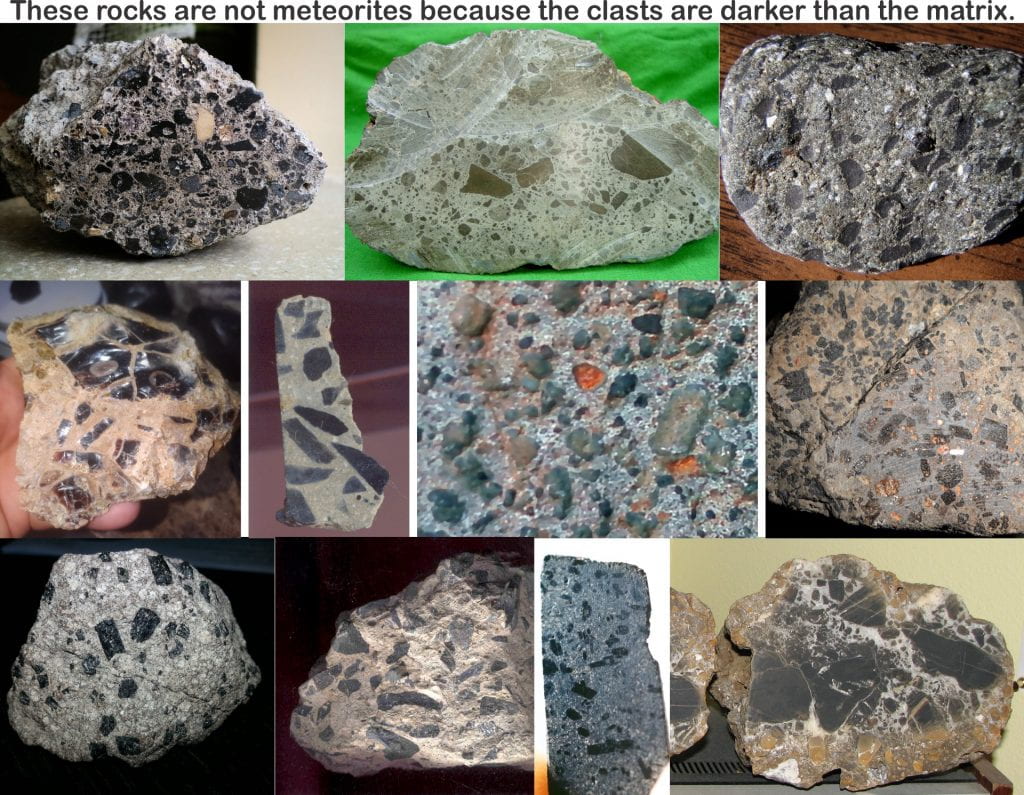

Dark clasts

A light-colored matrix dominated by dark clasts is only common among some HED meteorites (howardites, brecciated eucrites, and brecciated diogenites).

More photos

I am sent many photos of rocks that do not look like planetary impact breccias to me.

A story

Below are photos of a rock that an experienced and successful meteorite hunter asked me to analyze in 2006 because he thought that it was a lunar meteorite. He found it in Oman, where he has found several lunar meteorites. After sawing it in two (right), it looked pretty good then to me, too. It certainly looks like a breccia. Examining the photo now, however, I see my error. Most of the light-colored clasts appear to be the same rock type (= not polymict). The composition was definitely terrestrial and, of course, the rock has no fusion crust (which is not unusual for lunar meteorites from Oman). The rock is sedimentary, with high, compared to the Moon, concentrations of chalcophile elements.

A better story

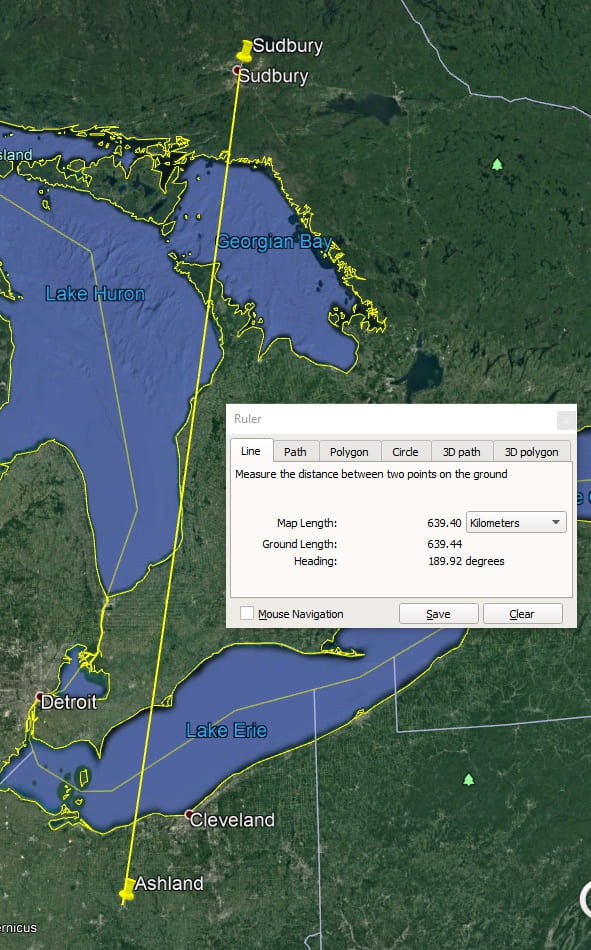

In 2014 geology professor Nigel Brush of Ashland University in Ashland Ohio sent me a photo of a rock that he had found in a local creek bed while on a field trip. He wanted to know if the rock (below) could be a lunar breccia.

I thought the rock looked enough like an impact breccia to pursue it, so we had a petrographic thin section made.

At the time this occurred, we happened to have one of the world’s experts on the terrestrial impact craters, Dr. Axel Wittmann, working with us. He took one short look at the thin section on the upper left, said “wait a minute,” walked to his office, and came back with the thin section on the right. He had collected the rock on a field trip to the Sudbury impact structure (euphemism for a highly deformed and eroded impact crater) in Ontario, Canada. The impact occurred 1.85 billion years ago. The rock was from the Onaping formation, a deposit of ejecta from the crater. The Onaping breccia has a distinct appearance and almost certainly Prof. Brush’s breccia also originates from the Onaping formation, 640 km north of Ashland. The rock was transported south to Ohio by glaciers, likely during the period of Pleistocene glaciation. Probably most of the rocks in the creek bed where Prof. Brush found the breccia were emplaced in the area during the Pleistocene glaciation. Glacial rocks are typically rounded from abrasion against other rocks carried south by the glaciers.

Nearly everything I say on these pages has an exception

Meteorite Picture of the Day: Tassédet 004 – H5 melt breccia

If someone had sent me these photos, I might have said that it was not a meteorite, except that there are rounded FeNi metal blebs in the impact melt , which proves that it is a meteoritic impact-melt breccia.