1803

- July 5: President Jefferson formally gives Meriwether Lewis instructions for an expedition west across North America in a Letter of Credit.

- July 29: William Clark accepts Lewis’s invitation to join him and begins to recruit men for the “Corps of Discovery.”

- August 31: Lewis makes his first journal entry as the Corps leaves from Pittsburg.

- (read the journal entries here)

- December 8: Lewis tries to obtain Spanish permission to travel up the Missouri River, but due to delays the captains decided to camp in St. Louis for the winter, dubbing it Camp Dubois.

- Recruits for the Corps of Discovery continue to arrive throughout.

Image Source: http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/inside/index.html

1804

- March 10: The Louisiana Purchase was officially transferred to the US, so Spanish permission was no longer needed.

- May 14: Clark began the journey without Lewis while Lewis completed business in St. Louis.

- May 16: Clark makes it 24 miles up the Missouri to wait in St. Charles.

- Their boat was too heavy in the stern and the water was rough, but there were no injuries.

- There is a lot of fallen timber:

- It’s necessary to load most weight in the bow (won’t get stuck on trees)

- May 17: There were multiple court hearings:

- Two men were charged for being absent without leave (received 25 lashes).

- John Collins charged for being absent without leave, behaving poorly at the ball, and disrespecting the commanding officer’s commands (received 50 lashes).

- May 21: The expedition left St. Charles.

- May 23: They stopped during their journey because too many people wanted to see them.

- They waited for Lewis to climb up a cliff up to a cave called the Tavern. During this climb he fell while he was 300 feet in the air; however, he was able to catch himself 20 feet into his fall with the aid of his knife.

- May 25: They passed through La Charette, the last non-native settlement on the Missouri River. This officially meant that, once Lewis and Clark left La Charette, they would not be in settled American territory.

- They were situated there to trade and hunt with Indians

- Mr. Louisel, down from Cedar Island, provided them with a lot of information

- Lewis writes 3 pages, including the changes in organization of their crew (lots of clerical information)

- May 31: Capt. Lewis went out to the woods and found many interesting plants and shrubs

- June 3: Lewis and Clark name their first geographical feature, Cupboard Creek, near the mouth of the Osage River.

- June 4: The mast of the boat broke.

- This same day Clark climbed up a hill that had 100 acres of dead timber on the top; some said they had found lead ore under the hill by the river.

- June 6: The mast was fixed

- Clark has a sore throat and headache

- June 7: Clark observed several painting and carvings in a limestone rock with white, red, and blue flint at the mouth of the creek.

- There was a den of rattlesnakes in these rocks (the river would kill some of them)

- Lewis wandered off with 4 or 5 men to some springs of salt water

- Lewis wandered off again on the 8th and saw the country was rich and full of high weeds and vines

- June 10: There was an abundance of water and deer

- Also an Osage plumb, double the size of a normal one

- Captain Lewis even killed a large Buck

- June 12th: They run into a party of fur trappers

- They purchased 300 pounds of buffalo grease to use as insect repellent

- They recruit Pierre Dorion, Sr. from the party to assist them in interpreting with Yankton Indians.

- June 16: ticks and mosquitos start to become quite a problem

- June 17: the French Higherlins start complaining that they want more food (they usually eat 5-6 times a day)

- Also, Clark’s cold is still very bad

- A war party against the Osages has boils and some have dysentery.

- June 20: Clark spots pelicans at a sand bar.

- June 25: They passed an area with a great amount of coal.

- June 26: The team reaches the mouth of the Kansas River, 366 miles from Camp Dubois.

- July 4: The first Fourth of July west of the Mississippi is celebrated, and the expedition captains name Independence Creek.

- July 21: They reach the mouth of the Platte River at the modern Nebraska-Iowa border, 630 miles from Camp Dubois.

- August 3: Near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, Lewis and Clark meet Otoe and Missouri Indian chiefs, handing out peace medals, in the first official parlay between the United States and western Native American nations,

- August 8: The expedition reaches Pelican Island 100 miles further.

- August 12: The explorers see their first coyote.

- August 20: Sergeant Charles Floyd is the first and only member to die on the expedition, possibly from a ruptured appendix.

- August 27: They meet members of the Yankton Nakota Indians in South Dakota and later hold a council with them, in which the Yankton entertain the idea of meeting the president. Dorion stays behind.

- September 7: The explorers see their first prairie dog town; the next day, Clark kills his first bison.

- September 25: Hostility arises in a council with Teton Lakota Indians when they demand a boat from the expedition, but their chief, Black Buffalo, managed to calm them.

- October 13: Private John Newman mutinies, but is court-martialed and banished to be a manual laborer for the party until he can be sent back in the spring.

- October 20: They see their first grizzly bear.

- October 27: The crew arrives at the Mandan and Hidatsa Indian villages which is home to more people than Washington, DC is at the time.

- November 2: They begin to build Fort Mandan 6 miles south of the Knife River to stay in for the winter, and enlist French Canadian Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife Sacagawea to join them as interpreters.

1805

- April 7: 31 men plus Sacagawea and her son Pomp set out westward in canoes. Lewis and Clark send a return party back to St. Louis with pelts, skeletons, soil, plants, minerals, artifacts, maps, letters, journals, and even live animals (most of which didn’t make it) intended for the President.

- April 25: The Corps of Discovery arrives at the Yellowstone River, 1888 miles from St. Louis.

- May 3: The crew makes it 2000 miles from base camp on the Poplar River, naming a tributary the 2000 Mile Creek.

- May 14: One of their boats capsizes, but Sacagawea saves the journals and other valuable papers from the water. Lewis and Clark name a creek after her as thanks.

- June 2-8: at 2508 miles, the Missouri River forks and progress is halted as they try to determine which is the true Missouri; Lewis and Clark correctly decide on the south fork.

- June 16-July 14: The crew must drag thousands of pounds of equipment, which had previously been transported by canoes, on an 18-mile detour around the Great Falls. The facts that Lewis tried and failed to build an iron-frame boat and that many men were injured in the ordeal created significant delays.

- August 11: At the newly named 3000 Mile Island near the Idaho-Montana border, a foot party briefly encounters a mounted Shoshone Indian.

- August 12: Lewis becomes the first white American to cross the Continental Divide at Lehmi Pass.

- Their shipment from Fort Mandan finally arrives in Washington.

- August 17: Clark holds a council with the Shoshone with the help of Sacagawea and are able to enlist one of them, Old Toby, to help them.

- September 11-22: The expedition makes a difficult journey crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, facing starvation before arriving at Weippe Prairie where they encounter the Nez Perce Indians.

- October 7: They set out on the Clearwater River along with Nez Perce chiefs Twisted Hair and Tetoharsky

- October 16: They reach the Columbia River, 3,714 miles from Camp Dubois. Old Toby has left at this point, and they meet numerous Plateau Indians.

- November 2: The explorers pass the furthest point reached by George Vancouver’s 1792 expedition.

- November 7: In his journal, Clark writes, “Ocian in view! O! the joy”, but the sea still 20 miles away and bad weather slows their progress.

- November 18: Lewis and Clark reach Cape Disappointment (previously named in 1788), the westernmost point of the expedition, in present-day Washington, 4162 miles from St. Louis.

- December 7: The crew begins work on their winter camp named after the local Clatsop Indians on the south bank of the Columbia.

- December 25th: The crew moves into Fort Clatsop.

Winter at Fort Clatsop

- The winter at Fort Clatsop was cold and rainy according to the expedition team. One expeditioner, Patrick Gass, recorded that “from the 4th of November to the 25th of March 1806, there were not more than twelve days in which it did not rain, and of these but six were clear”.

- During all the “free time” he had for winter to pass over, Clark was able to compile all the notes he took from the journey to complete a map from Fort Mandan to Fort Clatsop, which would be very helpful to future travelers.

- In order to survive, people apart of the expedition had to hunt for meat and for trading with the local Clatsop Indians.

- Right before Lewis and Clark left, they gave Fort Clatsop to the Clatsop Chief Coboway for all of his peoples help with getting them through the winter.

1806

- March 23: The expedition prepares to go home and hands over Fort Clatsop to the Clatsop Indian Tribe.

- This was the perfect time for the expedition to leave. If they had left to early, snow would still have blocked their path through the mountains. If they had left too late, they would have been caught in winter on the unsettled prairies.

- May 9: They stay at Camp Chopunnish near the Nez Perce, waiting for the snow to melt in the Rockies.

- July 3: The crew splits into two parties: Lewis continues east along the Marias River while Clark follows the Yellowstone River down south.

- July 27: Having camped with Blackfeet warriors the previous night and waking up with their rifles stolen, Joseph Field kills one of the Indians while Lewis mortally wounds another. They hastily ride back to the main party.

- August 12: Lewis and Clark are reunited. After two days they arrive back at the Mandan villages.

- August 17: The crew leaves camp and Mandan chief Big White agrees to go with them back to Washington.

- September 17: Lewis and Clark learn that many Americans presume them dead.

- September 23: After weeks of signs of American settlement, the expedition finally arrives in St. Louis. The Corps of Discovery disbands, Lewis is named governor of the Louisiana Territory, and Clark is appointed Indian agent for the West.

Significance of Lewis and Clark’s Expedition

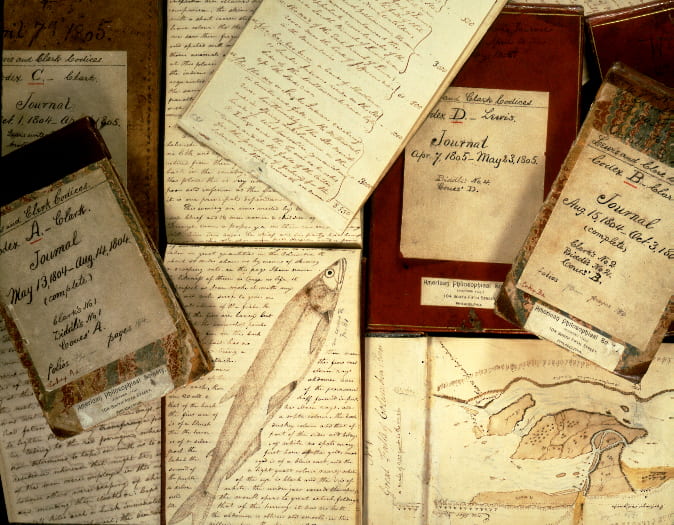

Lewis and Clark’s Expedition across America has been romanticized, demonized, and everything in between. Many people think the expedition was the physical start of manifest destiny in the American culture, which brought the extermination of cultures, bison and prairie lands. Many others see it as a true tale of American exceptionalism overcoming adversity. Both of these ways of looking at it might have some truth, and some embellishments; however, amid all the excitement and folklore over the expedition, I think there is at least one thing that professors and students can gain from the Lewis and Clark Expedition. That one thing is that nothing beats a good journal entry. Historian Donald Jackson stated that Lewis, Clark, and the rest of the team were the heaviest writers in exploration history. They documented every new or major thing they saw, whether it be the vast plains, the strange animals, the unique vegetation, or the enormous mountain ranges. They captured and preserved as much as they could, and then had notes good enough to report back to the President of the United States. These notes are still useful to researchers today. Lewis and Clark set a good example for field researchers like us: journal everything!

Image Source: https://www.archives.gov/nhprc/newsletter/2014/april

Although Clark’s journals are somewhat sparse, Lewis trained as a naturalist and took copious notes on the specimens he collected. Some days were a lot less eventful and I’m sure that some days his sickness prevented him from witnessing everything. Also, many things they saw were so new they were difficult to describe. This makes his journaling job even more difficult, since it would force them to pick and choose what they would journal; however, one thing is for certain, Lewis and Clark’s journals provide a great example of how important good notes are to biological and geographic exploration and study.

Bibliography

Woodger, Elin, and Brandon Toropov, Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. New York: Facts On File, 2004. Print.

United States, National Park Service. “Fort Clatsop.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 14 Oct.2016.

“Why Lewis and Clark Matter.” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian, n.d. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

“National Geographic: Lewis & Clark: Readying for the Return.” National Geographic: Lewis & Clark: Readying for the Return. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.