Metal, iron, & nickel

Take-home message

The metal in meteorites strongly attracts a magnet. If you have a piece of metal or a rock that contains metal but it does not attract a cheap ceramic (ferrite) magnet, then it is not a meteorite. Meteorites do not contain visible grains or chunks of nonferrous metals like aluminum, manganese, chromium, copper, brass, or gold. If you think you can “see gold,” then it is not a meteorite; the “gold” is probably just pyrite.

If you have a piece of metal that does attract a magnet and want to know if it is an iron meteorite, then obtain a chemical analysis for the elements iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), titanium (Ti), chromium (Cr), and manganese (Mn). Iron meteorites typically have 70-95% Fe, 5-30% Ni, 0.2-2% Co, and <0.05 % (<500 ppm) each of Ti, Cr, and Mn. A metallurgical testing lab can provide this analysis. I recommend testing for Ti, Cr, and Mn because most industrial (man-made) iron contains higher concentrations of these elements than does metal in meteorites. If the metal contains more than 0.05% titanium, chromium, or manganese, then it is not a meteorite.

In proper hands, a hand-held “XRF gun” can, nondestructively, provide concentrations of Fe, Ni, and Co that might provide compelling evidence that an iron meteorite is, in fact, an iron meteorite.

Iron-nickel metal

More than 95% of all meteorites contain iron-nickel (FeNi) metal. As a consequence, meteorites have concentrations of nickel that are much greater than that of nearly any terrestrial rock.

“Iron-nickel” means that the metal is mostly iron but it also contains 5-30% nickel. The metal occurs as two different alloys known as kamacite (lower nickel concentration) and taenite (higher nickel concentration). Both alloys strongly attract magnets. Neither alloy occurs naturally in Earth rocks, so a natural rock that contains kamacite or taenite is a meteorite.

| Many people tell me that they can “see” nickel in their rock. No. You cannot see nickel in a meteorite. You can see iron-nickel metal, but it is impossible to determine if the metal contains nickel just by looking. It requires a chemical analysis to determine if the metal contains enough nickel to be consistent with a meteorite. A metal detector cannot identify nickel. A positive response from a nickel allergy test kit (below) is not sufficient to prove that the metal contains enough nickel for the metal to be of meteoritic origin. See also the discussion of highly siderophile elements here. |

The metal in meteorites also contains a few tenths of a percent cobalt; the nickel/cobalt ratio in meteoritic metal is usually in the 10-25 range. Iron-nickel metal in meteorites also has high concentrations (by terrestrial standards) of rare metals like gold, platinum, and iridium. It is usually easiest and cheapest to test for nickel, however, because it is more abundant and easier to measure than the rare metals, which occur in concentrations much lower that can be detected by X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

Ordinary chondrites

Most metal-bearing meteorites are stony meteorites known as ordinary chondrites; the rest are other types of chondrites, brecciated achondrites, irons, pallasites, and stony irons (see statistics). Among ordinary chondrites, the most common type, H-group chondrites (45% of all ordinary chondrites), have the most metal, 15-20% by mass. L-group chondrites (40%) have some metal, 7-11%. LL-group chondrites (15%) have the least metal among ordinary chondrites, 3-5%. Because chondrites are rich in metal and the metal is rich in nickel, all chondrites have bulk (whole-rock) concentrations of nickel of 1.0-1.8% (i.e., 10,000-18,000 ppm). That is 100-1000 times greater than practically any terrestrial (earth) rock. An earth rock with as much as 1.0-1.8% Ni would be a nickel ore. In terrestrial rocks the nickel is not contained in metal, however, but in silicate and sulfide minerals.

One cannot determine if a rock contains high concentrations of nickel just “by looking.” FeNi metal looks just like Fe metal. A chemical analysis is required. Metal detectors cannot determine if a rock contains 1-2% Ni or that a chunk of metal contains 5-30% nickel.

Many people have told me, “But, I see metal!” when there really is no metal. Sometimes it is hard to tell the difference between metal and shiny nonmetals like some sulfide and oxide minerals or micas. If the “metal” is yellowish, then it is not metal but pyrite (“fool’s gold”). If the rock contains shiny bits but it does not attract a cheap ceramic magnet, then it is not a meteorite and the shiny stuff is not metal.

One easy test for grains or slabs that are at least a few millimeters in size is simply to measure the electrical resistance with an ohmmeter. You can buy handheld multimeters in any good hardware store for $30. In resistance mode (ohms), putting the leads some distance apart on any of these iron meteorites would give a low resistance – <100 or probably <10 ohms. This test may not work on an ordinary chondrite because the iron grains are not connected. Shiny hematite or pyrite aggregates will have high electrical resistance because they do not conduct electricity.

Some rare meteorites do not contain any appreciable metal and, consequently, they have low concentrations of Ni. For example, unbrecciated achondrites are poor in metal. In other words, many of the rarest types of meteorites contain little or no metal and have low nickel concentrations, just like earth rocks.

Iron meteorites

Iron meteorites are pieces of the core of a differentiated asteroid. Most are nearly 100% metal although many contain the iron sulfide mineral troilite. The concentration of nickel in iron meteorites, typically 5-30%, is much greater than that in industrial metals except for high-nickel steels. The concentration of nickel in industrial iron is usually <1%.

Note that unless it is very rusty, it is almost impossible to break an iron meteorite. Also, if you can cut an iron meteorite in two you are not going to find any vesicles or rounded holes, unlike many sample of man-made metals.

More iron meteorite photos

Meteorite Picture of the Day – Burns | Campo del Cielo | Canyon Diablo | Canyon Diablo | Canyon Diablo | Chinga | Elephant Moraine 84300 | Gibeon | Goose Lake | Henbury | Henbury | Hongshijing 003 | Magnesia | Morasko | Mundrabilla | Mundrabilla | Nantan | Nantan | NEA 051 | NWA 859 | NWA 859 | NWA 5549 | Odessa | Richland | Sikhote Alin | Twannberg | Uruacu | Xizang

Widmanstätten pattern

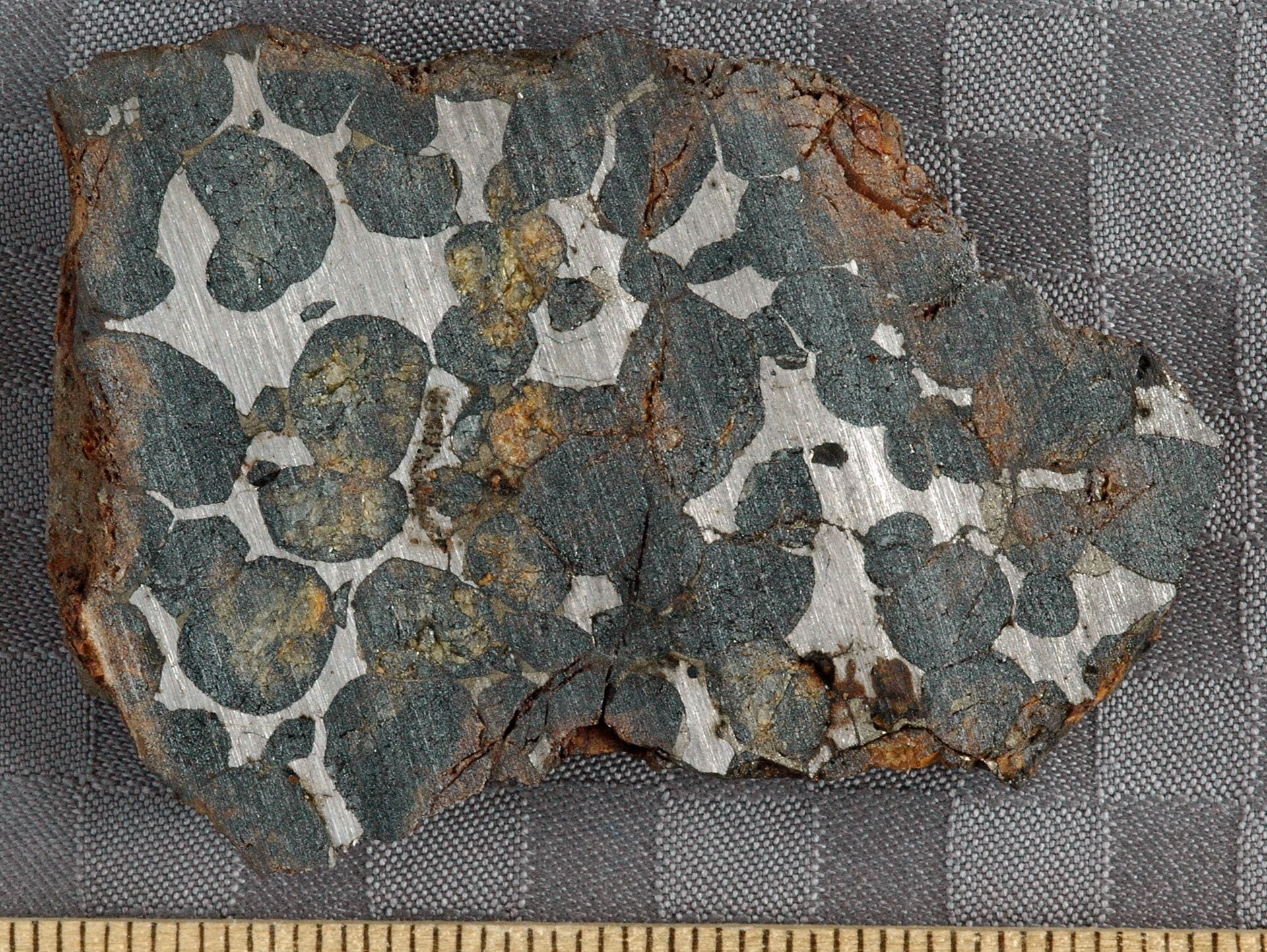

Iron meteorites are from the metallic core of asteroids. The iron cools so slowly that large grains of interlocking metal crystals form. If an iron meteorite is sawn, polished, and etched with an appropriate acid solution, the individual metal grains are revealed in a geometric array called a Widmanstätten pattern.

Many persons have told me that they cut a piece of metal and saw a Widmanstätten pattern so the metal must be an iron meteorite. I am not an expert on iron meteorites, but I think that is unlikely. Experts have told me that the surface must be ground (to get rid of the saw marks), polished, and acid etched to reveal the pattern because kamacite dissolves easier in acid than does taenite.

Widmanstätten patterns do not occur in stony meteorites. They are only seen in iron meteorites and pallasites. |

Pallasites and mesosiderites

Pallasites and mesosiderites are the two types of stony-iron meteorites. Only about 0.3% of known meteorites are pallasites and 0.6% are mesosiderites. Stony-iron meteorites are typically about 50:50 stone:metal.

Pallasites

Pallasites come from the boundary between the metallic core and rocky mantle of an asteroid.

More pallasite photos – Meteorite Picture of the Day

All of these photos are of cut and (many also polished) pieces.

| Eagle Station | Esquel | Esquel | Glorieta Mountain | Glorieta Mountain | Hassi el Biod 002 | Hassi el Biod 002 | Huckitta | Imilac | Imilac | Imilac | NWA 14492 | NWA 15134 | Marjalahti | Marjalahti | Sericho | Sericho | Seymchan | Seymchan |

Mesosiderites

Most mesosiderites are breccias formed by collision in asteroid belts of stony asteroids like eucrites and iron asteroids.

In photographs of mesosiderites, I have never seen one that I would call “attractive.”

Other metal-rich meteorites

Industrial slag

With a few rare and exceptions, naturally occurring terrestrial rock do not contain iron metal or iron-nickel metal. There are two reasons. First, the Earth formed from the same kind of material as the asteroids but early in Earth’s history the iron-nickel metal that it contained sank to form the Earth’s core. Second, any metal that did not sink has oxidized (rusted) over Earth’s long history. The Earth’s environment is far more oxidizing (oxygen atmosphere and water) than space, where meteorites originate. Earth rocks do contain iron and nickel, but only in oxidized (non-metallic) form. Therefore, if you find a rock that contains iron-nickel metal, then it is almost certainly a meteorite.

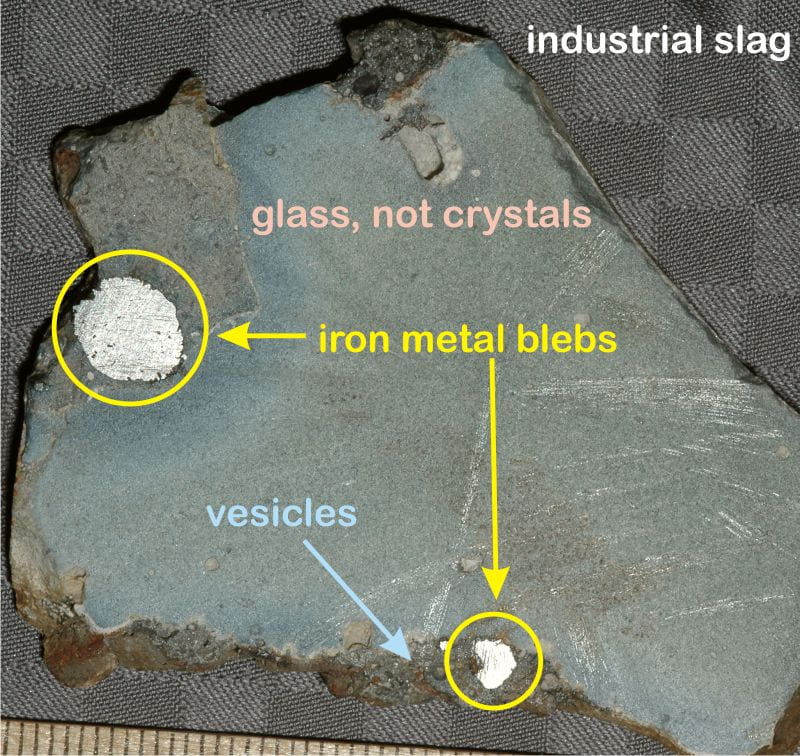

Many people find slags, other by-products of metal manufacturing, and man-made metal things. Some may have been from forges or blacksmith shops that are more than 100 years old. Others appear to have fallen from the sky for unknown reasons (see Getafe). Metal in slags and industrial by-products is mostly iron. Such materials will probably contain little nickel (much less than 1%). So, if you can determine that the sample has little or no nickel, then the sample is not a meteorite. Also, as noted above, the metal in meteorites has very low concentrations of chromium and manganese, <0.05%. These two elements are common in man-made metals, however.

Look at how metal grains are distributed in these photos of ordinary chondrites. The metal does not occur in big round globules. Globs are typical of slags. Notice that the metal is sufficiently soft that saw marks and smearing can be seen on the sawn faces. Sulfide minerals do not do that. Note that the meteorites do not contain vesicles. Vesicles (gas bubbles) are typical of slags, however.

Bottom Line

If you have a piece of metal or a rock that contains metal and the metal contains >5% nickel (Ni), then it is probably a meteorite. If the metal contains <5% nickel, however, then the metal chunk or rock is not a meteorite. Also, if the metal contains >0.1% chromium (Cr) or manganese (Mn), then it is almost certainly not a meteorite.

If you have a rock that contains between 1.0 and 1.8% nickel (whole-rock analysis), whether or not it appears to contain metal, then the rock might be a meteorite (ordinary chondrite).

If you have a rock that does not contain metal and has a low concentration of nickel (<1% = <10,000 ppm), then it could still be a rare type of meteorite, an unbrecciated achondrite. The probability is exceedingly small, however, because nearly all (guesstimate: >99.999%) Earth rocks have the same properties – absence iron-nickel metal and low concentrations of nickel (<0.3%).

The DMG test for nickel

I have had some success using a nickel allergy test kit to determine whether metal contains nickel. Such kits are available at well-stocked pharmacies and can be ordered on the internet. All such tests rely on DMG (dimethylglyoxime), which forms a complex that has a distinct pinkish color with ionic nickel or palladium.

Some people have allergies to nickel and metal alloys that contain nickel. The kit I tested was designed to determine whether “metallic objects” contain nickel. It consisted of 2 dropper bottles. “Solution A” was DMG in alcohol. “Solution B” was a weak solution of ammonium hydroxide in water.

The directions read “Place one drop of solution A and one drop of solution B on a cotton-tipped applicator (use equal amounts of both solutions). Rub wet applicator firmly against the test object for 15 seconds. If applicator turns red, the object contains nickel.”

Following these directions, I was unable to get a positive result on an iron meteorite that contains 6% nickel. The applicator did not turn red, but it did turn a rusty brown color. The problem, as I see it, is that the test requires ionic (oxidized) nickel and ammonium hydroxide does not liberate much ionic nickel from metal.

As an experiment, I applied a tiny drop of 1% hydrochloric acid (0.3 molar) to the meteorite, waited 15 seconds, and repeated the DMG test by swabbing the acid drop. This time I got a positive result (left). The acid dissolved a small portion of the meteorite, putting nickel ions in solution. The manufacturer of the test kit is not likely to suggest this work-around because hydrochloric acid is very corrosive and is likely to ruin jewelry and other metals if used incorrectly. (I rinsed the meteorite in much water after the test.)

As an experiment, I applied a tiny drop of 1% hydrochloric acid (0.3 molar) to the meteorite, waited 15 seconds, and repeated the DMG test by swabbing the acid drop. This time I got a positive result (left). The acid dissolved a small portion of the meteorite, putting nickel ions in solution. The manufacturer of the test kit is not likely to suggest this work-around because hydrochloric acid is very corrosive and is likely to ruin jewelry and other metals if used incorrectly. (I rinsed the meteorite in much water after the test.)

I tried the test also on a sawn face of an ordinary (H group) chondrite and also obtained a positive result.

So, what do you do? Hydrochloric acid is available to consumers is building supply stores as “muriatic acid.” It is used to clean mortar off masonry, among other things. It is extremely nasty stuff and may not be available in quantities less than a gallon, which is enough to ruin a significant portion of your car. Dilute it 50-to-1. The DMG test will not work if the solution is too acidic. Dilute battery acid (sulfuric acid) would probably also work. Some liquid toilet bowl cleaners contain ~10% hydrochloric acid. They are usually already colored, however.

Some people have contacted me saying that they obtained a positive result (pink color) when they applied this test to rocks that do not contain metal. I do not understand this. The test is designed for metal and the test is sensitive, but very few terrestrial rocks contain enough nickel to give a pink color. Remember, you are looking for strawberry pink, not rusty pink.

Note added later: I recently used this test on an iron meteorwrong that someone brought to us. When I used the nickel allergy test kit as is, the results are negative – no pink = no nickel. When I apply a bit of hydrochloric acid first, I did get a positive result – a pink cotton swab. Later, I did a real chemical analysis for Ni and obtained 600 ppm. This is a lot of nickel but is still 100 times too low for an iron meteorite. (Concentrations of cobalt, gold, and iridium were also much too low for a meteorite.)

The DMG test is very sensitive to nickel and can lead to a “false positive” with some metal samples. A negative (no pink) result probably means that the metal is not from a meteorite. A positive result means that it might be a meteorite or it might not! A correspondent who has done more research on this than I have claims that if the pink color fades away after 5 minutes, then the metal contains Ni, but not enough to be of meteoritic origin.