What are bees? Bee Basics

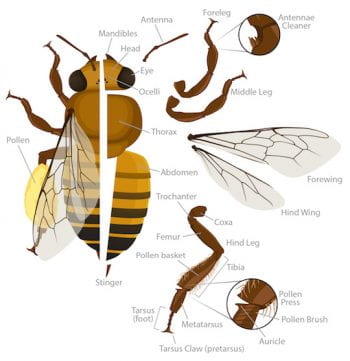

A honeybee anatomy chart. Taken from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/honey-bee-anatomy © Arizona Board of Regents / ASU Ask A Biologist.

Bees are insects that make up the clade Anthophilia (“antho-” and “-philia” are Greek for “flower” and “love” respectively, literallly “flower lovers”). As the name implies, the bees’ primary food source is nectar and pollen from flowers. As members of Insecta, all bees have a body divided into three segments – the head, thorax, and abdomen – as well as six legs, antennae, and the typical two pairs of wings; the hind wings are typically smaller than the fore wings and are folded beneath the fore wings when at rest.

Honeybee head. From Wikimedia Commons

On the head, a bee will five eyes. The two larger eyes on the side of the head are compound eyes, made of thousands of tiny lenses. Altogether, they allow the bee to perceive shapes, color, and light, including ultraviolet light which humans can’t see. The other three eyes are located in the center of ‘forehead’ on the top the bee’s head, in a sort of upside-down triangle arrangement. These are ocelli, or simple eyes, which help bees to orientate themselves and navigate to and from the nest. Near the bottom of the head is a pincher like pair of jaws, which allow bees to grip items or chew. Hidden behind that is the mouth, which includes a tongue structure called a proboscis that bees stick out to nip nectar. Also on the face between the eyes and below the antennae is a plate called the clypeus. Many bees will typically have markings there, usually white or yellow or sometimes red in coloration. These markings can be used to distinguish bee families or genera, and in some species they may be reveal the sex of the bee. For a more reliable method of determining sex, look towards the bee’s abdomen. You can count the plates that segment the top of the abdomen, as females will have six and males will have seven. Another obvious marker is the presence of a stinger, which only females have. Stingers used to be used by the modern bee’s ancestor as an egg laying structure, which is why males don’t have them.

A foraging bumblebee. Note the mass of pollen on the tibia, surrounded by hairs. Taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Bees are also noticably hairy or furry. This is due the fact that bees collect pollen as a food source, so the hairs help to pick pollen, which stick to the hairs as bees rummage through the flower. Later, the bees will brush themselves off, using their hairy legs to groom off the pollen. Female bees have special body parts for transporting pollen. A majority of species have a dense mass of hairs known as scopa, usually found on the legs, or the underside of the abdomen for megachilids; bees stick and trap the pollen between those hairs. However, members of the Apinae subfamily (corbiculate bees) use corbiculae, or pollen baskets, in place of scopa. The corbicula is a smooth, semi-concave area on the hind tibia surrounded hairs. Rather than trapping pollen between dense hairs, corbiculate bees tamp their collected pollen into that smooth region. Either way, whether it’s in a scopa or pollen basket, the pollen masses will stick to the bee as she carries it back to the nest for storage/consumption.

It is a well-known ‘fact’ that bees nest in large colonies, but that only really applies to honeybees, a highly eusocial species that clearly divides labor and assigns specific tasks among members of the colony. In honeybees, the differences between workers and the queen (and drones) are drastic, to the point where the queen is reliant on workers. The only other eusocial bees are bumble bees and some sweat bee species, but they are not nearly as social and structured, and are known as primitively eusocial. In primitively eusocial bees, only differences between the queen and the workers is size, but otherwise the queen is perfectly capable of functioning on her own. While workers are the ones who start up new colonies in honeybees, it is the queen who starts the nest in bumble bees/sweat bees. She collects the nectar and pollen and builds the initial nest, and after her first batch of daughters mature into worker bees, the queen gives up responsibility for nest care and foraging and stays at home to lay eggs, letting her workers take care of the other tasks. Compared to the thousands of members that make a honeybee colony, bumble bee and sweat bee colonies are tiny – bumble bee colonies range from around fifty to a few hundred, and a sweat bee nest might even have less than that, dipping down to just a dozen or so. Generally, eusocial species tend to be multivoltine, meaning they produce more than two generations a year, because the social structure of eusocial bees allows them to continue breeding throughout the year.

Nests of multiple alkali bees, a mostly solitary species. Taken from https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/alkali_bee.shtml

Other sweat bees are not eusocial, but semisocial. Several bees will share a nest and work together, but these groups smaller and last a single generation, not nearly as complicated as the larger, multi-generation colonies of eusocial bees. Semisocial bees do divide tasks, but there are multiple egg-layers instead of just one queen. Smaller bees tend to leave the nest to forage, while larger ones stay to build the nest or just lay eggs. Other bees have no such task division, because they don’t even work with others at all. A majority of bees are solitary, meaning a sole female makes the nest, forages for food, and lays the eggs. Once the nest is built and stocked with food for the laid eggs, the female seals off the nest and dies, never to meet her children. Thus, most semisocial or solitary species are univoltine (one generation a year) or sometime bivoltine (two generations a year). Although solitary bees build individual nests, they are willing to share space with neighbors. Some solitary bees nest in aggregations, meaning that multiple individual nests will be near each other – think multiple houses in a suburban neighborhood. Large aggregations may occur because that particular area has some qualities (soil, shading, proximity to food) that makes it attractive, resulting in a gathering of many bees. The large number of neighbors does carry a benefit in that predators are less likely to attack nests given the sheer numbers. Some bees will take it one step further and share a nest entrance. The bees all enter one way, but on the inside the females tend to their own individual nest tunnels/cells, similar to apartments or hotel rooms connected to the same lobby and door.

The bee taxas

You’re probably most familiar with the members of the Apidae family, especially Apis mellifera – the Western honeybee – but North American bees actually come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Behavior ranges wildly too; for example, while some are social, most are actually solitary, only foraging for themselves and caring for their own young. However, there are a few characteristics that define the various taxas of bees. Below is a list of bee taxons that can be found in Missouri:

Andrenidae (mining/sand bees)

The second largest of the bee families is appropriately composed of a diverse range of bees. Throughout the over 1200 species of Andrenidae bees, size ranges from just over half an inch to smaller than a tenth of an inch. Most species are strict specialists on certain flowers, their bodies having evolved to solely feed on them. All Andrenidae nest in the ground, preferably dry and barren, giving them the nickname of mining bees. Several nests can be found in the same area in close proximity, but these bees are in fact solitary. Individually, female bees use their mandibles and legs to first dig a tunnel straight down (from a few inches to a few feet deep) and then dig side tunnels branching out from the main one, ending in little chambers called nest cells for the larvae. They tamp down the walls of the nest using pygidial plate on the abdomen – structure commonly found in ground-nesters surrounded by some hairs – and then waterproof the nests through a secreted substance, with carries a bonus of protecting the developing young from bacteria in the soil. Many species begin collecting pollen and nectar quite early in the season, most becoming active around March or April. Using the collected pollen and nectar, the female forms small balls or loaves, places one in each chamber, lays an egg on each one, and then seals off the chamber. The larvae that hatch from the eggs will feed off the pollen balls they’ve been left with, developing in the chamber until the start of the next floral season, when the new adult bees dig their way out to restart the cycle. Subfamiles and tribes of Andrenidae in Missouri include Andreninae, Panurgini, Protandrenini, Perditini, and Calliopsini. Genera present in Missouri include:

An Andrena accepta. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright John Ascher, 2006-2014 / Discover Life

Andrena (mining bees):

As members the largest genera in the family, and one of the largest bee genera of world, Andrena exhibit a variety of behaviors. Some are generalists, some are extreme specialists to the point of only visiting a certain genus of flowers, and some are have preferences but are fine with foraging from other flowers. Some species have even taken to foraging from commercially grown crops like apples and onions. Foraging habits aside, Andrena nesting preferences also vary widely. Some species live next to just a few neighbors, others live in nest aggregations (multiple nests near each other) consisting of thousands. Some reuse the same areas for years, some burrow in new areas year to year. Some like hiding nest entrances near rock piles or under leaves, others leave theirs’ out in the open and can be spotted from the telltale mini-mounds of dirt piled next to the entrance. Some want sand, others want earth with clay, and some just nest in urban lawns. Despite the behavioral differences, one common thread between Andrena is how early they start foraging in the season (as early as February!). Some species crawl out up to a week before the surrounding flowers blossom, spending their time mating and digging burrows, surviving through their fat reserves as the bees wait for flowers to bloom. These bees are unusually cold resistant – a possible reason as to why they live at higher altitudes and latitudes than other bees – allowing them to tolerate the cold early spring weather when many other bees, including honeybees, aren’t yet active, making them excellent pollinators of early spring crops and plants. However, although they can survive cold weather, a minimum body temperature is still needed to fly, so Andrena can be spotted in the morning warming up under the sun on the ground, rocks, or leaves. Identification from a distance may be difficult as appearance varies; the color is usually shades of brown or gray, and the size is generally around and under half an inch.

Panurginus:

The only genus of the tribe Panurgini of the subfamily Panurginae, Panurginus consists of small (around a fourth of an inch) with little hair; they are darkly colored bees, sometimes with yellow markings on the face, legs or thorax. Pollination wise, Panurginus includes both generalists and specialists on flowers like mustards, roses, and buttercups. These bees dig shallow nests (less than a foot) with a fourth of an inch wide entrance holes. When the female is present the hole is plugged, but when out foraging the hole is left open; either way there are no dirt mounds surrounding the holes, setting them apart from Andrena. Panurginus can reuse nesting sites and can live in nest aggregations, though some species may also live communally.

Protandrena:

One of the three genera of tribe Protandrenini, these bees are quite similar looking to their cousins in Panurgini – black coloration with yellow markings, little hair – though one way to tell the difference is size, as Protoandrena are a bit larger. Timing is also a clue, as Panurginus pop up earlier in Missouri around the end of March/early April and are active until around the end of August. Protandrena appear later around the end of April/beginning of May, but stick around longer until October. Protandrena include both specialist and generalist foragers. Females from this genus are solitary and dig individual nests, but do nest in aggregations. Females prefer sparser ground with more sunlight, but still place entrances near stones and patches of vegetation. Perhaps it’s to hide the nest from predators, though it’s also possible it’s for the female’s own benefit since it marks the nest and helps her find it when she finishes foraging for the day.

A Pseudopanurgus compositarum. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Edward Trammel / Discover Life

Pseudopanurgus:

Again, these bees are quite similar to Protoandrena, the only differences being less yellow on the legs, a very slight decrease in size, and a slightly different active season, appearing and lasting just a bit later. Some Pseudopanurgus specialize on members of Asteraceae, known as the sunflower family. For nesting, these bees prefer open ground and nest in dense aggregations.

Anthemurgus:

There is only one species in this last genus of the Protandrenini tribe, and it’s Anthemurgus passiflorae. This relatively rare bee is black with yellow face markings, measures around three-tenths of an inch, and is active from April to August. Unusually, this species is bivoltine, meaning that two generations are produced in a year. A. passiflorae specializes on foraging from only one species: its namesake, the yellow passionflower. However, it does not pollinate them very well, as the females (like other members of the subfamily) have little hair and instead collects pollen using its mandibles (jaws). While the bees do place harvested pollen on their legs like most other bees, A. passiflorae also coats the pollen in nectar, which prevents the collected pollen from sticking onto other passionflower stigmas for pollination. Like its cousins, A. passiflorae are solitary bees that prefer open, barren ground, but they only form loose aggregations.

Two Perdita ignota. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org J. Devalez / Discover Life

Perdita:

Perdita is another large genus, consisting of bees with diverse appearances and colors, though one commonality is size. While some may be relatively ‘normal-sized’, many Perdita bees are tiny in comparison to other species – in fact, Perdita includes, the smallest bee in North America, Perdita minima, which is under a tenth of an inch long. These bees are largely desert dwellers, and as such have adapted to specialize on specific flowers such as globe mallows and prickly pears. While some have crepuscular behavior to forage from flowers blooming only at dawn and dusk, many prefer working in the day and can easily tolerate the summer heat. Active seasons range from early spring to late fall, as a species’ emergence tends to depend the blooming of flowers they specialize in foraging from. Emergence can also depend on humidity levels, as those can correspond to rainfall and thus blooms in the desert. Most Perdita nest solitarily, a few communal. Most prefer nesting in sandy soil, though a few are particular about where to nest, requiring sandstone, limestone, cracks in mud, or lake beds, to name just a few. This may be due their specialist behavior combined with their miniscule size, which makes flying far difficult and forces most to live relatively close to their food.

A female Calliopsis andreniformis specimen. Taken from the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab / Encyclopedia of Life

Calliopsis:

Calliopsis bees are around four-tenths of an inch, and are generally dark colored with light grayish hair and yellow face markings, and will often have yellow bands on the abdomen. Another resident of deserts and other dry areas, Calliopsis are also specialists for various plants or at least have strong preferences, and are usually active the summer and fall, maybe mid-spring if they specialize on a flower that blooms then. Calliopsis dig shallow nests and prefer hard-packed earth or soil that is alkaline or contains clay, and specialists will also typically nest close to food sources. Oddly, the males will also dig little holes, although only at night to sleep in. Female Calliopsis also have a quirk, in that they bury their holes coming and leaving, compared to the standard behavior of leaving the entrance open when out foraging. All are solitary, though some species may nest in dense aggregations, resulting in a bit fighting between males when emergence/mating season arrives.

Colletidae (cellophane, masked, and fork-tongued Bees)

Colletidae consists a variety of rather diverse and behaviorally unique bees. All are solitary, though some may form aggregations. The two main subfamilies present in Missouri, Colletinae and Hylaeinae, have one genus present each:

A mating pair of Colletes inaequalis. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Micheal Veit 2010 / Discover Life

Colletes (plasterer/polyester/cellophane bees):

Colletes are generally decently sized bees, reaching up to just under four-fifths of an inch. Colletes bees are rather hairy, and have pale-yellowish/gray fur on the head and thorax and black abdomen with white/gray bands. Diets vary widely, as some are specialists on certain flower families or genera, though others are generalists. They are active from around mid-March to September. All are solitary ground-nesters that prefer little vegetation – some species can be very picky about soil type and only live in certain areas corresponding to those conditions. As such, nesting sites tend to be reused for many years, forming large, dense aggregations of bee nests. What gives Colletes their common names is what they line their nest cell walls with. Colletes have flat, broad, short forked tongues, which they’ll use to cover the walls in their saliva, followed up with a layer of secretions from a gland on the abdomen (interestingly, Colletes lack the pygidial plate that other ground-nesters have). This mixture creates a durable substance that is remarkably similar to clear cellophane, giving the nest a water and mold resistant wall where the eggs are stuck to. As a further layer of protection, Colletes secrete another substance from the base of their mandibles that is spread which protects the larva from bacteria and fungi. Rather than making hard loaves, female Colletes transport pollen internally in a crop – a stomach like storage organ – and then regurgitate a soup-like pollen, nectar, and water mixture, leaving it in the nest for her offspring to feed on.

A Hylaeus leptocephalus. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014 / Discover Life

Hylaeus (masked & yellow-faced bees):

Hylaeus are smallish, dark-colored bees with little hair and pale yellow/white marks on the legs and face. A key identifying feature is the unique facial markings for Hylaeus species which give the genus its name. While there are other bees with white-yellow facial marks, masked bees tend to have distinct patterns that extend past the antennae or eyes. The also distinct lack of scopa (pollen collecting hairs) may be explained by how, like Colletes, Hylaeus eats pollen and nectar and carries them in the crop. This also makes Hylaeus poor pollinators, as pollen can go directly into the crop and never have the chance to stick to another flower. Although they can use their mandibles to directly harvest and eat pollen from anthers, those mandibles are too weak to dig holes. Instead, the bees find pre-made holes, usually in wood and hollow stems, holes made from other bees or other creatures, and even man-made holes like nail holes. Still, like their cousins, masked bees also line their nests with the same substances and the cellophane-like layers to water and pathogen-proof them.

Melittidae (melittid bees)

Melittidae is such a small family that there’s only thirty-three species in North America total. However, they are also probably one of the oldest bee families – the oldest bee fossil to date, an specimen trapped in amber discovered in Myanmar, was found to be of an ancestral family related to Melittidae. The 100-million-year-old age of the fossil indicates that Melittidae ancestors were around not too long after the first flowering plants appeared. All modern melittid bees are solitary ground nesters, and a majority are specialist foragers, though the flowers of choice vary quite widely within the genera; closely related species may forage from entirely different flower families or even different orders. Though these bees are relatively rare, there are still three different tribes with a genus each present in Missouri, and those are Hesperapis, Melitta, and Macropis

A male Hesperapis carinata specimen. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Smithsonian Institution Entomology Department / Discover Life

Hesperapis:

The largest of the three genera, Hesperapis contains twenty-five North American species. They are generally dark colored with grayish hairs and lightly colored bands on the abdomen, and are around hald an inch (plus or minus a tenth) in size. As ground nesters, Hesperapis live in deserts and grasslands, having a preference for loose, sandy soil, and nests can be marked by the small deposit of soil near the entrance. Their nests are noted for being very deep – reaching over three feet! – and having long side tunnels. Unlike other ground families like Andrenidae and Colletidae, these most Hesperapis bees don’t line the walls with any kind of covering substance, with the exception of a few that line the nest cells with mixture of fine soil and saliva. For most Hesperapis species living in the desert, active periods last from March to October. Those species are bivoltine, with one generation produced in the spring and another in the late summer which correspond to the two blooming periods following the heavy spring and summer rains. The other univoltine species are only active from March until early June.

Melitta:

The largest of the Melittidae genera worldwide has just four species total living in North America. They have darkly colored bodies covered with quite a bit of light brownish or grayish hair, particularly on the thorax and head, and their size is roughly the same as Hesperapis. Their active period ranges from March to June. While not much is known about these elusive bees, researchers do know that they are all specialists. One species in particular, M. americana, specializes in blueberries and cranberries, and is a particularly important pollinator for these berries for a few reasons. For one, they can buzz pollinate, a special technique used by some bees where they vibrate the anthers to shake out the pollen firmly stuck inside. Regular visiting honeybees would be able to extract very little or no pollen, as they lack the ability to buzz pollinate, so they are very ineffective as pollinators for these plants. Furthermore, because M. americana is a specialist on cranberries and blueberries, that greatly increases the pollen reaches the right flower, as opposed to a generalist forager who visits a large variety of plants. These two behaviors combined make M. americana a fantastic pollinator for American blueberries and cranberries.

Macropis:

This genus also has just four species in America, ranging from three-tenths to half an inch. Active periods range from May to August. Macropis bees look much like their relatives in Hesperapis, being darkly colored with gray hair, but with a key difference – their hind legs are notably thick and hairy. The hairs on the hind legs are designed to absorb floral oils from loosestrife flowers, a trait all members of Macropis shares worldwide. Interestingly, loosestrife flowers don’t produce any nectar – the adult bees get nectar from other flowers – so females instead collect floral oils from loosestrife, and instead of mixing nectar with pollen, Macropis mixes the oils with pollen to feed to their young. The water-resistant oil is also used to line and waterproof the nest cells, as Macropis prefers fine, well-drained soil and digs very shallow nests just a few inches deep. Despite the small size, these nests are also very compact, each nest typically having many cells compared to other ground nesting families. Their nests can be found on sloped banks, the entrances often covered by a bit of growing vegetation, and the same areas are often reused for many years.

Halictidae (sweat bees)

Halictidae is another very large and diverse family, with behavior and physical traits varying quite widely. Common traits that most members share include smaller size, short tongues, and bright and/or metallic coloration, but those aside, not much else unites this massive group. One behavior that scientists research is the variation of sociality in Halictidae species. On one end, there are eusocial species that form small colonies. On the other end, there are solitary nesters. In between, there are communal nesters and semisocial species, and uniquely, some of the eusocial species will opportunistically swap their sociality depending on conditions. Further unique traits will be detailed below when discussing individual genera. There are four tribes/subfamilies in Missouri: Halictini, Augochlorini, Nomiini, and Rophitinae. Genera include:

A male Agapostemon splendens foraging. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright John Ascher, 2006-2014 / Discover Life

Agapostemon (striped-sweat bees):

All members of this genus have a stunning bright green, metallic coloration on the head and thorax, giving rise to a nickname of ‘metallic green bees’. Females of most species keep that coloration for the abdomen, but males instead have a black and yellow striped abdomen, though few may have metallic black (female) and red and white (male) coloration on the abdomen instead. Those stripes on the males give them part of their other common name of striped-sweat bees – the sweat part comes from an occasional tendency to drink human sweat, a trait shared with some other genera. They are medium sized, ranging from three-tenths to six-tenths of an inch. Active periods lasting from late March to October. Agapostemon as a whole don’t seem to be very picky. For a start, they are generalists foragers. Nesting preferences are also diverse within the group: Agapostemon nests can be found in many types of soil ranging in content, soil fineness, and moisture level; including lawn dirt, fine sand, and silt. Horizontal, vertical, and sloped ground are all possible nesting sites. Agapostemon are fairly tolerate of sharing the space with other bees, living in vicinity with other members of the genera and even species from other families, and a few opportunistic Agapostemon species will take advantage of this situation to take over another bee’s built nest and remodel it for their own young. Despite this willingness to share space, they do not form aggregations, though some species may nest communally in small groups if required to.

A female Halictus ligatus foraging. Taken from Wikimedia Commons

Halictus (furrow bees):

These bees have about the same size range as Agapostemon, and are darkly colored with light gray hairs and white bands on the abdomen. Males will also have addition yellow markings on the legs and on the face below the antennae. All are generalists, so they have a broad active period ranging from March to early October in the Missouri region. There are only ten species in the US, but Halictus bees are fairly abundant and common. Halictus social behavior varies even within a species, as some may act eusocial or solitary depending on conditions. When behaving socially, their structure works a bit different than honeybees. A colony begins when a female bee, or sometimes two, digs out a nest and lays a bunch of eggs. The foundress(es) cares for the eggs on her/their own, and eventually all the eggs hatch into workers. The founding queen (if there’s two, one becomes a worker) then switches to just egg laying, while her workers take care of other duties like larva care and foraging. Unlike honeybee and bumblebee workers, these sweat bee workers still keep a fully working reproductive system and can lay eggs, but their queen usually bullies the smaller workers into subordination. Workers can become a queen if the current queen dies, or if they leave the nest to establish their own colony, but the latter only happens under certain conditions. Size is a factor, as smaller bees can be more easily bullied, and are also less likely to survive a winter on their own so it’s more beneficial to stick to a colony. How much pollen bees eat as larva impacts their size – more pollen means larger bees – so weather will effect sociality. Spotty and unpredictable weather leads to fewer flowers, which leads to less pollen for larva, which leads to smaller bees and thus promotes eusocial behavior. In contrast, when the weather is good and flowers are abundant, the workers are fed more pollen and turn out larger, and are thus more likely to strike out on their own. However, Halictus in areas with colder weather and shorter flowering periods are more likely to be solitary, because the season isn’t long enough to establish a multi-generation colony. Either way, Halictus prefer sandy areas, usually reusing areas and sometimes living in aggregations. They dig eight inch to three feet deep tunnels, with side branches containing either nest cells, for solitary bees, or brooding chambers, where eusocial bees care for and rear their eggs and larva; the youngest generations are stored in the deepest parts of the nest while the older ones are closer to the top.

A Lasioglossum bruneri. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Tom Murray / Discover Life

Lassioglossum:

This is actually the largest and most diverse genus of bees, containing 290 species in five different subgenera in the US. Despite their relative abundance, they may be a little hard to notice due to most species’ relatively small size. The active periods for these bees range from Febuary to October. Like their relatives in Halictus and Agapostemon, Lassioglossum have a taste for salty human sweat, and most are ground nesting, though some nest in rotting wood. Appearance varies widely, usually relatively hairless and a dark or a dull metallic green or blue color, sometimes with white bands on the abdomen. Males will also have longer abdomens and a more slender body. Social behaviors run the gamut from primitively social and semisocial, to communal and solitary, to even parasitic. As you can see, the Lassiogossum group doesn’t have many commonalities due to sheer size of the genus, though some species do stand out for their unique traits. L. coeruleum, one of the aforementioned wood nesting species, actually use preexisting burrows of beetles or other insects. A female starting a colony will modify the tunnels to hold nest cells, and the subsequent generations of workers continue to build tunnels, nest cells, and brooding chambers, eventually forming an elaborate system of interconnected tunnels and rooms within the wood. Two other subgenera, Hemihalictus and Sphecodogastra, stand out for being specialists among generalist foragers. Hemihalictus consists of just L. lustrans, a springtime species with preference for chicories and false dandelions. Sphecodogastra consists of eight North America-exclusive species that specialize on evening primrose. Because they bloom during the evening, some species have larger ocelli to help them fly in darker conditions. They also have specialized bristle hairs to gather the long, sticky threads of pollen that evening primroses produce. Lastly, the species of the subgenus Evylaeus are unique for building chambers and combs in their ground nests. The chambers are supported by mud columns, and the combs are separated by thin walls made from a combination of a waxy secretion and soil. Because it takes several females to build this structure, the sociality of these bees are either semisocial or primitively eusocial.

A female Augochlora pura. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014 / Discover Life

Augochlora:

Augochlora, Augochlorella, and Augochloropsis are all genera of the tribe Augochlorini. The names refer to the Greek words for ‘exceedingly green’, alluding to the bees’ vivid metallic green full body coloration. All of them are of a medium or smaller size, are generalists, and are active from around April to September. Differences between the three lie in nesting behavior. With the exception of one eusocial ground nesting species, all Augochlora are solitary bees that nest in rotting wood. In the fall, female bees seek out beetle burrows in wood, crawl in, and chew straight down until reaching the soil. While chewing, the sawdust created is shoved behind her, creating a sawdust packed tunnel with a little chamber at the end called hibernaculum. There, the bee will hibernate until April, when she’ll emerge. The females then spend their spring foraging during the day and building their nests at night, and by June, her offspring emerge to restart the cycle.

An Augochlorella aurata. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Sheryl Pollock 2011 / Discover Life

Augochlorella:

Augochlorella are instead eusocial ground nesters, and may form aggregations. They are multivoltine, producing three generations in a year. The first generation is the fertilized female that starts the nest in the spring. In June, after building a nest and caring one generation of young, the female becomes a queen and her daughters become her workers. Those workers take care of one laid egg at a time until maturity, and by September the colony will have raised the complete third generation. The females from that last generation will then overwinter in a hibernaculum and emerge in the spring to continue the cycle.

A metallic blue Augochloropsis metallica. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Ted Kropiewnicki / Discover Life

Augochloropsis:

Augochloropsis are relatively rare in the US. They are all communal ground nesting species. Interestingly, Augochloropsis leaves their larvae perfect cubes of pollen and nectar, as opposed to the loaves or balls that other bees make.

A Sphecodes heraclei. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Machele White / Discover Life

Sphecodes:

Most bees are known for being hard, diligent workers, but a few other bees will happily piggyback off their efforts. These bees don’t collect pollen and don’t build nests, instead laying their eggs into another bee’s nest. The bees will typically find a nest still being filled with pollen, and while the true owner is out foraging, the parasite bee will enter and lay her eggs in the various cells. Then, the larvae that hatches from those eggs will kill the true owner’s eggs or larvae before eating the pollen left for them. These types of bees are known as kleptoparasites, or cuckoo bees. Sphecodes is one such genus of bees, specifically preying on members of the family Halictidae with a preference for the above six genera. Sphecodes species are active during the same times as their preferred hosts. Like other cuckoo bees, Sphecodes look similar to wasps, having little hair. They range from around two-tenths to half an inch, and are black with red abdomens. Sphecodes are unique among kleptoparasites for killing host larvae/eggs themselves rather than leaving their larvae to do it.

A Nomia nortoni inspecting a rock. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Patrick Coin / Discover Life

Nomia:

Nomia is made of medium-sized black bees with thick, faintly iridescent bands on the abdomen and slightly dark tinted wings. They are active from May to October. All are generalists, but one species called N. melanderi, also known as the alkali bee, is particularly important for pollinating commercial alfalfa. Honeybees can’t really fulfill that role quite well. For one, they don’t really like living in the climate where alfalfa is grown; for another, accessing pollen in an alfalfa flower requires a special technique that honeybees don’t know but alkali bees do. As a result, some farmers have created artificial salt flats next to the alfalfa fields for these bees to nest in, as alkali bees prefer salty/alkaline moist soil. Many bees can occupy a small area, as Nomia is noted to nest in extremely dense aggregations – in one case, scientists recorded over 700 nests in just a square yard. Overall they are solitary, though some may nest communally and just share a main tunnel, possibly to save time on digging through the hard upper soil layers they like.

Dieunomia:

This genus contains larger bees that can reach just under an inch in size. They are dark colored bees, and many have red abdomens and wings darkly tinted at the end tips. They are active from May/June to October, flying around the blooming time of the flowers they specialize on: the sunflower family. Dieunomia nest in the ground, and noted to nest in plowed but unsown farmland. Thus, Dieunomia nesting areas shift year to year, depending on which fields are open for use at the time. Dieunomia nesting areas will be pretty noticeable, due to both their dense and large aggregations and the large mounds of dirt they leave at the entrance (as in, a handful of dirt sitting in a pile). Most bees in the aggregation will generally dig their own nest, but some will just look for abandoned nests and start storing pollen in it. Some bees may even skip the pollen collecting step, parasitizing their own species by leaving their eggs in another bee’s nest – though this behavior seems to be rather uncommon so far and has been rarely observed.

A Dufourea marginata on a human palm. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Jelle Devalez / Discover Life

Dufourea:

A somewhat common genus, these bees are generally dark colored with tufts of gray hairs, sometimes having a light metallic sheen. In terms of body shape, Dufourea tends to be smaller and more slender. Active periods range from March to September. Some are generalists when just looking for nectar to drink, but all species will only gather pollen from a specific family or genus of flowers, though which flower family varies widely within Dufourea. Dufourea can be difficult to find, as they are solitary ground nesters that form only loose aggregations. Furthermore, the entrances tend to be covered by leaves, forest floor debris, or stone piles. Nest entrances can be marked by not only small mound of dirt, but also a small trough like trail, formed from the bee shoving the dug up dirt mounds away from the nest entrance. Dufourea dig shallow nests that are only five to eight inches deep and line them with nectar to harden the walls. Inside, females store spherical pollen balls coated with a secreted substance that prevents the pollen from fungus.

Megachilidae (leafcutter, mason, resin bees and allies)

Megachillidae is a unique family with several characteristics that differentiate it from other families. Bees from this family tend to have rounder and thicker body shapes, as opposed to slightly flattened shape seen in other bee families’ side profiles. Another dead giveaway is the carrying of pollen under the abdomen, a behavior no other family displays. Many bees from this taxon will have larger mandibles used to chew wood – they bore nest holes in wood – or grip objects, as many opportunistic members will grab leaves, resin, mud, and other materials to build their homes. Other equally opportunistic species will nest in almost any holes, natural or manmade. The four subfamilies/tribes from Megachilidae in Missouri are Lithurginae, Osmiini, Anthidiini, and Megachilini, and the genera belonging to them are:

Lithurgopsis (northern cactus woodborers):

These are dull black bees with thin but clear white bands on the abdomen. Bees from this genus can be distinguished from a pygidial plate on the abdomens of males or raised ridges on the ‘foreheads’ of females. They are uncommon in Missouri, having a preference for dry areas. As their common name implies, these bees specialize on cactuses and bore their own holes in wood. Lithurgopsis are unique for not using preexisting holes and boring their own holes from scratch, usually in rotting wood or man-made wood structures. The bees chew one main tunnel with several side branches containing nest cells, which are separated by walls of sawdust or pollen.

A blue orchard bee. Taken from Wikimedia Commons

Osmia (mason bees):

Osmia bees have distinct metallic sheens and cool toned colors, including green, deep blue, deep purple, or black. They are active from February from September, and some are generalists but there are many specialists. Many of the flowers Osmia favors are tube-shaped or asymmetrically shaped, so to help them extract pollen, the bees many have stiff or corkscrewed shaped hairs to pull pollen out. Another common shared preference is flowers from the rose family. This preference makes one species, known as O. lignaria or the blue orchard bee, particularly important for pollinating orchards of apples, almonds, plums, and cherries, all of which are from the rose family. Not only are they faster and more efficient than honeybees, but they are also active during these crops’ early springtime blooming. Osmia are solitary bees who are a bit lazy when making a nest. Some may attempt to use mud and stones to build something, but most seek out preexisting holes in the form of abandoned bee nests, beetle burrows, hollow plant stem, stone cavities, or even snail shells or pinecones. They will mark the entrances of these holes with their own unique scent – reported to be somewhat lemony – in order to distinguish their home from neighbors. Osmia will typically have just one main tunnel with no side branches, instead the nest cells are created one at a time starting from the back – one nest cell is created at the tunnel’s end and then sectioned off by a mud partition, the next segment of the tunnel creates another cell sectioned off by mud, and so on. Aside from mud, some species may also carry back sap or chewed up plant matter for the walls or leaf pieces to line the cells. Female eggs are stored towards the back and males in cells closer to the front. When it comes time to emerge, the bees will chew their way out, even pushing through siblings in the cells in front of it if they haven’t emerged yet.

A female Hoplitis producta specimen. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Laurence Packer 2014 / Discover Life

Hoplitis:

These bees are darky colored with white-banded or red abdomens; often they will have distinguishing antennae that taper into slight hooks. They have active period ranging from April to around August, and most prefer cooler climates and/or mountainous regions. Hoplitis contains both generalists and specialists, with common preferences including flowers from the waterleaf, pea, or borage families. Most species display nesting behavior similar to that of Osmia, being solitary species that seek out preexisting holes and arrange the tunnels the same way. A few will use a saliva and soil ‘mortar’ to paste pebbles together into an exposed nest cell. Multiple cells are built right next to each other, touching each other, and after all are built the cells are covered with another mortar layer. Despite exposure to the open air, the final structure is actually sturdy enough to be reused or built on top of, which subsequent generations sometimes do.

A foraging Heriades leavitti. Note the pollen stuck beneath the abdomen, Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright John Ascher, 2006-2014 / Discover Life

Heriades:

Heriades are fairly small bees that are darkly colored with white bands and a patch of white hairs beneath the abdomen, used for pollen collection and transportation. The abdomen is typically kept curled and was somewhat of a wavy outline, due to the rounded individual abdominal segments. They are all generalist species, observed to be active from June to September. Heriades primarily nest in abandoned insect holes, particularly beetle burrows in wood, or in pinecones. They too use just a single tunnel, partitioning the cells with resin.

A Chelostoma philadelphi hovering next to a nest hole. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014-2015 / Discover Life

Chelostoma:

Species from this genus have slender body shapes with slightly elongated thoraxes and the typical patch of white hairs for pollen collection. Coloration is black, and bands on the abdomen are thin, faint, or nonexistent. The jaws are quite noticeably large and long and end with teeth, as opposed to the single tipped ends of other mandibles. These bees are relatively uncommon but present in Missouri, and have short active periods ranging from April to June. Nests are based in preexisting insect nest tunnels in wood, and cells are partitioned by soil mixed with resin or nectar.

An Anthidium manicatum. These commonly seen bees are actually an introduced species from Europe. Taken from Wikimedia Commons

Anthidium (wool-carder bees):

These common bees are generally medium to large in size, ranging from three-tenths to nearly a full inch. Most species have a bright yellow and black coloration not too different from yellowjackets, though the stout round body shape is indicative of an Anthidium bee. Anthidium mandibles have noticeable teeth, Their active periods are from March to September. Research on foraging preferences is still in progress – some seem to be generalists or have preferences, but others have oddly shaped face hairs like Osmia, indicating they may be specialists. Anthidium generally live in dry areas like deserts. Females will typically find preexisting holes in plant stems, wood or ground (including abandoned insect nests), or man-made structures. Anthidium have a habit of lining nests with scraped off plant fuzz from leaves and stems, giving them their common name of wool-carder bees. Once females have finished with stocking the nest and laying their eggs, they will pack the entrance with fuzz, pebbles, and bits of wood and plant matter. Another nesting quirk of Anthidium is laying the male eggs in the deeper cells instead of the typical front cells. This is because the males in this species are larger than females, so they are placed in the back for extra time to develop. As adults, these large males will spend time guarding flower patches, guarding their territories from other competitors and even other insects. Given that they live in the desert, it makes sense that males will guard the few floral resources within the area.

Anthidiellum (rotund-resin bees):

Antidiellum essentially look like miniature Anthidium but with more prominent black coloration. Aside from being half the size, these bees can also be distinguished by the stripe color at the base of their black heads, near where the head meets the thorax, and by their rather smooth (but still teethed) mandibles. They are reported to be active from May to September are all generalists, though some seem to have a slight preference for sunflower family plants. These solitary bees don’t use holes, instead choosing to build their nest out in the open. These nest cells, made of mostly resin, can be found stuck to rocks and branches.

Dianthidium:

Another genus from the same tribe, Dianthidium species look like Anthidium and Anthidiellum with their black and yellow coloration. They are closer in size to Anthidiellum, but can be slightly larger. These bees are generalists active from May to October, though many prefer foraging from the sunflower family. A unique trait of Dianthidium is that females don’t become less attractive after mating. In the majority of other bees, males will stop attempting to mate a female after she has mated once, but male Dianthidium will continue to hover above nest sites for more mating chances. The solitary Dianthidium females build nests in preexisting holes in wood and plant stems or abandoned insect burrows, or on banks and stable sand dunes. Many will also build nests out in the open on top of exposed rocks or twigs, sticking together plant matter, soil, and pebbles using resin, usually collected from sunflowers. They might also cover the surface with more pebbles or mud to hide the nest cells from predators.

A Megachile inimica foraging from a crownbeard flower. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright John Ascher, 2006-2014 / Discover Life

Megachile (leafcutter bees):

This yet another particularly large and diverse group of bees, containing both large and small bees. Megachile vary in appearance, but most will have black or gray bodies, lots of hair, large mandibles, and whitish bands on the abdomen. Females will have a lot of scopa (the pollen collecting hairs) on their belly, and males will have unusually rounded rear ends that curve out and down quickly. Species are active from April to October, and this genus includes both generalists and specialists. One species is especially managed by farmers for the purpose of pollinating alfalfa, known as M. rotundata, or the alfalfa leafcutter bee. However, this species is not native to the US, and like honeybees, was brought over for the purpose of pollinating plants. Most Megachile nest in preexisting holes with the exception of a few that dig nests in the round. They are solitary but willing to share space with neighbors, so they mark their nest with a personal scent to aid in finding the nest when returning home for the day. As the name ‘leafcutter bee’ implies, these bees do precisely that – if you notice rounded cutouts in the leaves or petals of plants, it was likely the work of leafcutter bees. The edges of the leaf pieces are chewed to make them sticky, so that the female can then form individual little capsules for her young from stuck together pieces of leaves. Most aren’t choosy and just use any suitable leaves or petals, but there are some pickier species. Many species show a preference for rose, lilac, or evening primrose, and on species called M. montivaga strongly prefers farewell-to-spring flower petals. Of course, a few members break the trend and don’t use leaves. Some partition the space into nest cells using walls of sand, mud, pebbles, or sap. One species named M. policaris doesn’t even make individual nest cells, instead placing a large quantity of pollen in one large chamber and then laying the eggs in pockets of the pollen mass, and the hatched larvae grow together in the chamber.

A Coelioxys sayi. Note the conical pointed abdomen. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014-2015 / Discover Life

Coelioxys (cuckoo-leafcutter bees):

These bees range from a smallish to large size. They are darkly colored with white bands on the abdomen, and often have red coloration on the abdomen and/or legs. The genus can be easily recognized by the cone shaped abdomen; the rears of males have a few spines, while females have a tapered pointed end. Coelioxys are kleptoparasites, so females use those pointy ends to stab a hole into the nests of Megachile and lay their eggs in there. The Coelioxys larvae kills the host eggs or larvae after hatching and then eats the stored pollen.

Stelis:

Some bees of this tribe are wholly dark colored or a dark metallic blue, but others look like the Anthidium bees they share a tribe with. Despite that relation, these bees are actually cuckoo bees that parasitize bees from the Megachilidae family. Not much else is known about them and other cuckoo bee families; because they don’t build nests, researchers can’t reliably study their day to day actions.

Apidae (carpenter, cuckoo, bumble, honey, and other bees)

This is by far the largest family of bees; the US alone has around a thousand species in fifty different genera. Some of the most recognizable bees sorted into this taxon, including honeybees, bumblebees, and carpenter bees. Many bees in this family are particularly important pollinators. Aside from the honeybees that pollinate a majority of the world’s crops, many members of the families are specialists; furthermore most of them have quite a lot of hair, making them excellent pollen transporters. In this section, we’ll be focusing on the following tribes from the subfamily Apinae – Emphorini, Eucerini, Anthophorini, Bombini, and Apini – as well as the subfamilies Xylocopinae and Nomadinae. Genera from these subfamilies and tribes include:

A Diadasia australis foraging on pricky pear, with pollen on the legs. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org J. Devalez / Discover Life

Diadasia:

Diadasia are yellow and brown bees ranging from two-tenths to eight-tenths of an inch in size. They are rather hairy, particularly on the legs, as those long and stiff scopal hairs are needed to carry the large grains of pollen they collect. These bees are relatively uncommon in Missouri, having a preference for deserts and grasslands. Though they will take nectar from any flowers, specialists when foraging for pollen. Most members specialize on either the cactus or the mallow flower family; some may specialize on a genus from this family, including bush mallows, poppy mallows, hollyhocks, and checkerblooms. Female Diadasia are solitary and prefer hard-packed dirt. To dig a nest, females will use their mandibles and saliva to loosen and soften the ground, digging a straight tunnel about a foot deep; in the bottom of this main tunnel she digs out a bunch of nest cells. One at a time, the female stocks the cell with pollen and nectar balls with the egg and seals it with mud, repeating the process until all the nests cells are filled and sealed. The female will then seal off the whole nest before starting an entirely new nest to repeat the process. Diadasia nests are noticeable, partially because they prefer barren ground and nest in aggregations, but primarily because nest entrances are marked with turrets, which give them the nickname of chimney bees. Females reuse the soil they dig up to construct little cylindrical walls surrounding the nest opening. Some species may also add a bent section at the end to form a periscope like structure. The reason why the bees make these turrets is still being researched; current theories include protection from weather and/or predators, making the nests recognizable, or use as a sunbathing/warm up spot in the morning.

A Ptilothrix bombiformis, also known as the hibiscus bee. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014-2015 / Discover Life

Ptilothrix:

These bees are medium sized, ranging from around three-tenths to half an inch. They have black bodies with a coat of yellow-brown, fuzz like hair on the thorax. Ptilothrix looks fairly similar to some bumblebees, but can be differentiated by the presence of scopa on the hind legs. If there’s a lot of long hairs on the tibia instead of a smooth shiny spot, then it’s a Ptilothrix bee. These bees are active from May to September and are specialists on morning glories or hibiscus flowers. Like Diadasia, these bees nest in hard-packed earth and build turrets, though you may notice additional small balls of mud surrounding the turret. That’s because Ptilothrix uses a different method of digging. The bees seek out large enough bodies of water and drinks up while standing on the surface like a water strider. Then, she flies back to the nest site, using the water to turn hard soil into soft mud. As the female digs deeper, the mud is rolled into pellets and deposited at the enterance.

A Melitoma taurea specimen. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Johnny / Discover Life

Melitoma:

As relatives from the same tribe, Melitoma look and act fairly similar to Ptilothrix. These bees are roughly the same size and have the same dark coloration and hair on the thorax, but the thorax hair is a bit darker in color and may have dark patterning. Additionally, Melitoma will also have thin white bands on the abdomens. Like Ptilothrix, Melitoma are active from May to September and are specialists on morning glories. They prefer hard-packed soil with clay and also use water to soften soil, so nests are often near water.

A male Eucera hamata specimen, Note the long antennae. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Laurence Packer 2014 / Discover Life

Eucera:

Eucera is a genus from the tribe Eucerini, along with the seven other genera below. Male species from this group are known for having very long antennae, giving them the nickname of long-horned bees. Another characteristic of the tribe is the noticeably protruding clypeus (the plate on the face below the antennae), with the clypeus of Eucera in particular protruding out a bit more. Eucera tend to be dark colored, medium to large sized bodies with a lot of whitish yellow or brown-yellow hair, with bands on the abdomen that wrap all the way around. These bees are active from March to Augusts and include both generalists and specialists, with the specialists usually foraging from pea family plants. Eucera are largely solitary with a few communal nesters. They prefer sandy or clay containing soil on flat ground or shallow embankments/riverbanks. Like with many other ground nesting bees, the nest entrance of these bees are often marked with mounds of soil.

A male Melissodes agilis. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture / Discover Life

Melissodes:

Melissodes look like Eucera bees, but can be differentiated by their later active periods. These bees are active from June to late October, and many specialize on the numerous sunflower family plants that bloom during this time. Melissodes bees are ground nesting, sometimes forming aggregations or communal nests. Some species dig a unique nest structure: the main tunnel goes straight down for a few inches, bends and runs parallel to the surface for a bit, and then goes straight down again for another few inches. The soil from digging out the half below the bend ends up piled in the upper half, forcing the female to dig through loose dirt every time she enters or leaves. From the lower half this main tunnel, the females dig out another few side tunnels, each containing a vertical nest cell lined with waxy secretions. Once the pollen and egg have been placed inside the nest cell, females will seal it by burying the cell in soil and packing the side tunnel with more soil.

A Peponapis pruinosa sticking out its tongue, Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014-2015 / Discover Life

Peponapis & Xenoglossa (squash bees):

These two closely related genera go by the name of squash bees. Appearance-wise, there are differences. Both medium to large sized bees with a coat of tan-yellow fuzz on their thoraxes, but Peponapis will have dark bodies with bands on their abdomens, while the slightly larger Xenoglossa have rufous bodies; male Xenoglossa will have additional yellow or white marks on the face. While Peponapis is active from July to early October and Xenoglossa is active from late April to August, both are active during the blooming period of the plant they specialize on: squash. Squash bees are one of the most important and effective pollinators of wild and domesticated squash and squash relatives (e.g. pumpkin and zucchini). Because squash flowers bloom early and wilt in the noon, squash bees awake early in the morning, oftentimes before daylight, to pollinate these flowers. By the afternoon, male squash bees will stop to nap in the wilted squash flowers, while females return to work on the nests. The solitary squash bees nest in ground; their nests are typically a foot and a half deep or more. They prefer to nest close to their food sources, so you can find nests in the grounds next to a squash growing farm.

A female Svastra obliqua specimen. Note the large scopa on the hind legs. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Laurence Packer 2014 / Discover Life

Svastra:

These bees are generally large in size and have banded abdomens and dark colored bodies largely covered in yellow hair. The scopa on the hind legs of Svastra are large and numerous, looking as if a pair of extremely poofy fuzzy socks were placed on the legs. Svastra is generally active from May to October, and the genus contains both generalists and specialists on flowers families like sunflowers, cactus, and evening primrose. This genus includes both solitary and communal species that nest in dense aggregations. Their nests are typically ten or so inches deep, with more or less horizontal side branches containing vertical nest cells. These cells are waterproofed through a thin lining made from a mix of the female’s waxy secretion and soil.

Cemolobus:

This genus has one species called C. ipomoeae, a relatively rare species that lives in the lower Midwest. These medium-large sized bees are easily identifiable by the three distinct lobes protruding from the lower clypeus – a central rectangular lobe with two triangles to the side. This species is active from May to October during the blooming period of the flower their scientific name refers to, the morning glories (Ipomoea). Like with squash, morning glories wilt by the noon, so C. ipomoeae awake early to forage.

Florilegus:

Only a single species of this genus, F. condignus, lives in the US. It is a medium sized, dark bodied bee with yellow fuzzy hair, similar to Eucera, though F. condignus has a distinctive pattern of bands on the abdomen; males have can be distinguished by a yellow clypeus. Even less is known about this bee, though we do know it’s been active from April to September, and that members are specialists on pickerelweed.

This Anthophora abrupta looks similar to bumblebees, but have scopa on the tibia. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org Sam Houston / Discover Life

Anthophora:

With their larger size and stout, dark colored bodies, Anthophora look similar to bumblebees, though Anthophora have larger faces closer to their thorax in width, and many member have gray instead of yellow hair. This is a large genus with many members, but most are rare. These bees can tolerate colder temperatures and are active from March to September. The genus includes both generalists and specialists, including flower families like evening primrose and creosote. Both Anthophora and Habropoda are part of the tribe Anthophorini, known as the digger bees. Anthophora do indeed dig nests in banks, shoveling dirt into piles near the entrance using their front legs and using their mandibles when the dirt grows too hard.

Habropoda:

Habropoda are extremely similar to Anthophora both in appearance and behaviors. One difference is an earlier active period starting around February and lasting until July. This genus also includes generalists and specialists. One specialist, H. laboriosa or the southeastern blueberry bee, is a specialist and very efficient pollinator of blueberries, as it has the ability to buzz pollinate. Like Anthophora, these bees nest in dense aggregations. Unusually, the bees don’t always emerge yearly, with some larvae delaying their emergence for up to ten years. This strategy of having a portion of the generation emerge late is called bet-hedging, and it helps save part of the population in case that year’s floral resources happen to be low.

A Common Eastern Bumblebee (B. impatiens). Taken from Wikimedia Commons

Bombus (bumblebees):

These medium to large bees are pretty well known and widespread, with their distinctive fat black bodies and fuzzy yellow coats of hairs. That thicker coat, combined with an ability to warm up via shivering their flight muscles, allows many bumblebees to tolerate colder weather, so their active periods are from March to September. Bumblebees are all generalists, and many can access and pollinate plants that honeybees can’t due to their ability to buzz pollinate. Many vegetables, including tomatoes, eggplants, and potatoes, all require the service of bumblebees in order to be pollinated. Bumblebees are one of the few eusocial genera, though their colonies function differently that honeybees (see section ‘What is a bee?’). A queen starts a nest herself in the spring, seeking out large cavities like abandoned rodent burrows, hollow wood, leaf litter, or holes in buildings. After gathering a good amount of food, she then spends most of the time caring for her first batch in the nest and only really leaving to gather more food. Once the first batch of workers mature, she switches to egg-laying duties while workers care for other needs, laying generations of sterile female workers throughout the summer. In the fall, the queen lays a generation of male bees and queens. The old queen and workers will die, and so will the males after mating, but the fertilized new queens will hibernate over the winter and emerge to start a colony in the spring.

Bombus subgen. Psithyrus (cuckoo bumblebees):

This subgenus of bumblebees gets its own section for their unique behavior as kleptoparasites of other bumblebees. They don’t really look all that different from other bumblebees except for a key difference in the legs. Standard pollen collecting bumblebees will have a hairless shiny spot on the tibia called the pollen basket, used to transport masses of pollen. On Psithyrus species, however, the tibia has a dense mass of hairs, as these bees do not need to gather pollen. What female Psithyrus do is they sneak into a bumblebee nest and kill the queen, taking her place. She tricks and/or bullies the workers into subordination through the use of pheromones and physical aggression, and the workers will care for the false queen’s eggs and larvae until they mature and set out to take over colonies of their own.

A European honeybee foraging. Taken from Wikimedia Commons.

Apis (honeybees):

These arguable the most well-known and common genus of bee in the world. Only one species lives in America –Apis mellifera, or the European honeybee, and it’s technically not even native to America. Though they were originally from Europe, this species has taken root as an important pollinator for both wild and crop plants. Honeybees are generalists that will collect nectar and pollen from any flower. Honeybees are unique among bees for both their highly eusocial behavior, complex social signals, and the mass quantities of honey they produce. Most bees turn their nectar into honey, as it only needs to be stored as sustenance for the larva while they are still developing outside the active season. However, honeybees are technically active throughout winter, so colony needs honey to consume to stay alive during the cold months. Unfortunately, all that honey also makes them prime targets for many predators, so honeybees have modified stingers. Most bees have smooth stingers that allow for multiple stings, though most generally avoid doing so. Honeybees, on the other hand, have barbed stingers attached to vemon sacks. If the skin of the creature being stung is thick enough, the stinger and the vemon sack becomes lodged in the victim’s skin. Unfortunately, this process also rips a hole in the abdomen, killing the worker eventually.

An Eastern Carpenter Bee robbing nectar from a daffodil. Taken from Wikimedia Commons

Xylocopa (carpenter bees):

Xylocopa includes the largest bees on average, many of them are around half the size your thumb. The hairs on the body are short, and in some commonly seen species the abdomen is shiny from a lack of hair. Carpenter bees are active from March to September. They are generalist foragers, but not necessarily good pollinators. On one hand, their large bodies can carry a lot of pollen, and though they are generalists, when preparing for the nest the bees will typically visit just one type of flower, increasing the chances of pollination. On the other hand, carpenter bees are unable to access the pollen or nectar of many flowers due to their large size, so some species will outright chew holes in the flowers’ bases to sip the nectar and never touch the pollen, a behavior known as nectar robbing. They are able to chew a hole using their power mandibles, the main purpose of which is to chew holes into plant matter. Some species will nest in hollow stems, others chew into solid pieces of dead wood, natural and man-made. If you find a near perfectly circular tunnel in your porch wood with a small scattering of fine sawdust beneath the hole, that was probably the work of carpenter bees. The solitary female carpenter bees are univoltine or sometimes bivoltine; unusually, the mothers will be around when their eggs hatch and will care and guard the developing larvae over the spring. Meanwhile, the male carpenter bees will have set up territories, hovering near entrances and fiercely guarding them from other males, and also other living things passing by. By fall, the larvae will have developed into adults, but the daughters will stay with the mother in the nest to overwinter, and by next spring they will set out independently to start a nest.

Ceratina (small carpenter bees):

These bees are of a medium to small size. They generally hairless and have black or metallic green or blue coloration, and may also have white marks on the face. The majority (barring one California species) are generalists active from March to October. Like larger carpenter bees, small carpenter bees also nest in wood, but are unable to chew the hard outer layers with their smaller mandibles. Instead, these bees find stems or hollowed twigs that are already damaged or dead. Then, they can chew through the softer pith (plant tissue) inside the stem to make nest cells. Like Xylocopa, Ceratina is solitary but guards her young until they develop into adults, even opening up sealed cells to check on them.

A Nomada texana drinking from a crownbeard. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright John Ascher, 2006-2014 / Discover Life

Nomada (nomad cuckoo bees):

These small to medium sized cuckoo bees look extremely wasp-like, especially with their red or black and white coloration. A good way to tell them apart from wasps would be to see if they fold their wings over their back, a characteristic of bees. Most Nomada are kleptoparasites of Andrena bees and will lay multiple eggs in a single nest cell, but only the first one to hatch will survive, as it will kill off the host’s egg and its own unhatched siblings. During daylight hours, these bees can be found perched near aggregations, looking or waiting for an unattended nest. But during the night, because they have no nest to return to, Nomada and other cuckoo bees will typically cling onto the end of a stem or twig with their mandibles, leaving their bodies stiffly dangling with their legs tucked in. They will ‘sleep’ the entire night in that position until waking up the next morning.

An Epeolus bifasciatus forages from mountain mint. This species has more red coloration and markings than white. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014 / Discover Life

Epeolus (cellophane-cuckoo bees):

The most of the medium sized Epeolus have rather stark black and white coloration that form bands on abdomen, which may also have red markings in some species. Females have additional spines for breaking past the cellophane-like layers of the nest cell walls of Colletes, the genus all Epeolus parasitize. Using the spines, the egg is laid between two layers and stuck to the lining with a substance secreted by the female, with the egg’s tip touching the inside of the nest cell.

A Triepeolus lunatus, with the smiley face on the thorax visible. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014 / Discover Life

A sleeping Triepeolus lunatus. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Hadel Go 2014 / Discover Life

Triepeolus:

These bees are also black and white in color, but are generally larger than Epeolus and have red legs. Additionally, the white pattern on the black thoraxes of many species is said to look similar to distinctive ‘smiley face’. Triepeolus parasitize many bee genera in different families. They typically find their hosts by following a foraging bee back to her nest, laying eggs into the cell wall of the host’s nest cells.

A Holcopasites calliopsidis perched on a stem. Taken from https://www.discoverlife.org © Copyright Micheal Veit 2010 / Discover Life

Holcopasites:

These smallish bees have interesting patterns: the black head and thorax usually have white marks, and the red abdomens typically have white and/or black marks and sometimes a black patch near the end. They primarily parasitize bees from the subfamily Panurginae in the family Andrenidae.

Things that are NOT bees

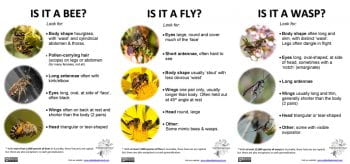

If you are trying to identify an insect that might be a bee, one quick way to tell bees apart from similar looking wasps and flies is the hair. Most bees are much furrier than the smoother wasps and flies, and while wasps may also have hairs, they are much less dense and are thin and simple, compared the the dense, plumose (feathery) hairs of most bees. As mentioned before, bees are hairier because they use those hairs to collect pollen for food, while wasps are predatorial and thus have no need for those hairs. That also explains the cuckoo bees’ similarity to wasps – since they leave their young in other bees’ nest, they don’t need to collect and transport pollen, so they don’t need hairs either. If you can observe the insect for longer, look at proportions: wasps will generally have skinner bodies with longer, hairless legs, while bees usually have thicker bodies with shorter, hairy legs. In addition, wasps will generally hold their wings to the side, parallel to the body, while bees hold theirs folded and flat over the body.

As members of a different order, flies are even easier to tell apart from bees and can be distinguished from in a few different ways. A glance at the face can tell you whether you have a fly, which have fairly short antennae, or a bee, which have longer, clearly geniculate (elbowed) antennae. If you have a good view, you can check if the insect has clear mandibles or a smooth proboscis portruded to sip nectar – if so, you’re looking at a bee. You can also look on the back for the number of wings. Flies only have one pair of wings; in fact, the name of their order, Diptera, is Greek for “two wings”. Bees on the other hand have two pairs of wings. Look closely, as many bees tuck their hind wings beneath their fore wings, giving them the appearance of having only two wings when they have four. The way the wings are held are usually different as well; while the bees usually fold their wings over each other on back, the flies typically spread their wings in an arrow shape when at rest. Other differences of flies include far larger eyes and a lack of a thin, pinched waist between the thorax and abdomen – a key characteristic setting Hymenoptera members like wasps and bees apart from other insects.

To summerize:

Bibliography

Akwardbotany. (2015, March 14). Year of pollination: The anatomy of a bee. Retrieved November 9, 2018, from Akward Botany website: https://awkwardbotany.com/2015/03/14/year-of-pollination-the-anatomy-of-a-bee/

Anthophila (Apoidea) – bees. (n.d.). Retrieved November 8, 2018, from BugGuide website: https://bugguide.net/node/view/8267/tree

Ball, S. (2006, November 6). 100-million-year-old discovery pushes bees’ evolutionary history back 35 million years. Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved from http://news.cornell.edu/stories/2006/11/two-studies-bee-evolution-reveal-surprises

Burlew, R. (2013, June 2). Chimney bees and their turrets. Retrieved November 8, 2018, from HoneyBeeSuite website: https://honeybeesuite.com/and-now-chimney-bees/

Camilo, G. R., Muñiz, P. A., Arduser, M. S., & Spevak, E. M. (2017). A checklist of the bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 90(3), 175-188. https://doi.org/10.2317/0022-8567-90.3.175

Cane, J. H. (2008). Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Apiformes). In J. L. Capinera (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Entomology (Vol. 2, pp. 419-434). Retrieved from https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/20800500/EncyclopediaofEntomologyCaneBees.pdf

Canadian Pollination Initiative. (2012). CANPOLIN Bee Course 2012 Key to Bee Genera in Canada. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a849d4c8dd041c9c07a8e4c/t/5a9726bbe4966bfb36b7c1eb/1519855307853/CANPOLIN+Bee+Course+Key+and+Notes.pdf

Dr. Biology. (2017, June 13). Bee anatomy. Retrieved November 8, 2018, from ASU – Ask A Biologist website: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/honey-bee-anatomy/

Encyclopedia of Life. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2018, from https://eol.org/

Graham, J. R., Ellis, J., Hall, G., Nalen, C. Z., & Buckley, K. (2016, May). Anthophora abrupta. Retrieved November 8, 2018, from UF IFAS Featured Creatures website: http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/ creatures/misc/bees/anthophora_abrupta.htm

Grimaldi, D., & Engel, M. S. (2005). Hymenoptera: Ants, bees, and other wasps. In Evolution of the insects (pp. 407-467). Retrieved from Google Books database.

Moisset, B., & Wojcik, V. (n.d.). The Alkali Bee (Nomia melanderi). Retrieved November 19, 2018, from United States Department of Agriculture website: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/alkali_bee.shtml

Moisset, B. (2010, November 26). Native Bees of North America (L. Anton, Ed.). Retrieved November 9, 2018, from BugGuide website: https://bugguide.net/node/view/475348

San Fransisco State University. (n.d.). Bee Vocabulary. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from http://online.sfsu.edu/beeplot/pdfs/bee%20vocabulary.pdf

Spevak, E. M., & Arduser, M. (n.d.). Missouri bee identification guide [Leaflet]. Retrieved from https://www.stlzoo.org/files/9413/3303/3161/MO_Bee_Guide_w_boarder.pdf

Wilson, J. S., & Carril, O. M. (2015). The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.