The encumbrances of time and distance have been decreased by the automobile and infrastructural networks, but speed comes with risk. The art historian Sydney Pokorny noted that the theorist Paul Virilio’s analysis of speed assigns to it the power of “dissolving human will, producing an accelerated world filled with passengers locked in a zombie-like trance…a ‘dis-appearance into a holiday where there’s no tomorrow,’ an endless rehearsal of todays stretched out and held over indefinitely.”[4] In the frenetic condition produced by the automobile, human will and agency are, to some extent, lost. Yet we still find ourselves bound to the allure of speed in our pursuit of perpetual motion through a destabilized context.

The desire to go fast, and to watch others move at high speed as in recreational racing, not only outweighs the violent nature of speed, it is motivated in part by the danger of a potential collision. Robert Stanley’s painting Crash, 1966 (Indianapolis 500) (1966) and Doug Aitken’s film fury eyes (1994) present us with a picture of acceleration’s allure. Aitken’s film underlines that the will to speed is tied to the desire for control and dominance, particularly as it relates to the figure of the white American male. The film’s opening text introduces its content: “On August 13, 1993, at Palmdale International Raceway, Ron Fringer plans to ride a motorcycle running on 99% methanol and 1% alcohol at 190 miles per hour.” The attainment of speed would seem to be the dominant focus, yet the slow-motion footage never affords us a view of the film’s promised peak velocity. The camera mounted on the motorcycle faces the driver’s chest, creating a picture that appears static, only offering hints of acceleration through the motor’s roar and the wobbling of the recording. At 175 miles per hour, however, the video’s capacity to record breaks down, and the picture becomes illegible, ultimately revealing a loss of control.

Ruscha’s Royal Road Test (3rd edition, 1971; first published 1967), completed with Mason Williams and Patrick Blackwell, reflects on the nature of speed’s destruction, but with entirely different parameters. On “August 21, 1966, at 5:07 P.M.,” in “perfect” weather, Ruscha performed a Consumer Reports–style crash test, dropping a vintage typewriter from a 1963 Buick LeSabre traveling ninety miles per hour along US Highway 91. The project’s title references both the typewriter manufacturer and the Royal Road—“the original highway” of the ancient Persian Empire, now an aphorism for efficiency. The book is a face-off between two machines—car and typewriter—and a confrontation between the two dominant linear threads in Ruscha’s work: words and the road. Like an ironic forensic catalog documenting the typewriter’s parts strewn across the southwestern landscape, the book traces the material evidence of speed’s destructive power.

The wall-mounted sculpture Hanging Herm (1974) by John Chamberlain reveals the fragility of a car’s metal enclosure. To create this work Chamberlain crumpled a selection of painted or chromium-plated steel scraps from the body of a car, compacting the large-scale, flat sheets into a compressed, three-dimensional sculpture. Metal is malleable and can be crushed, underlining that the fact that, despite the sleek, powerful affect of its design, the car is nothing more than a destructible and destructive object. Crash, Royal Road Test, and Hanging Herm hint at the most dramatic consequence of vehicular speed: injury and death. Vehicle crashes are one of the leading causes of avoidable injury and death in the US and are the number one cause of death among the young.

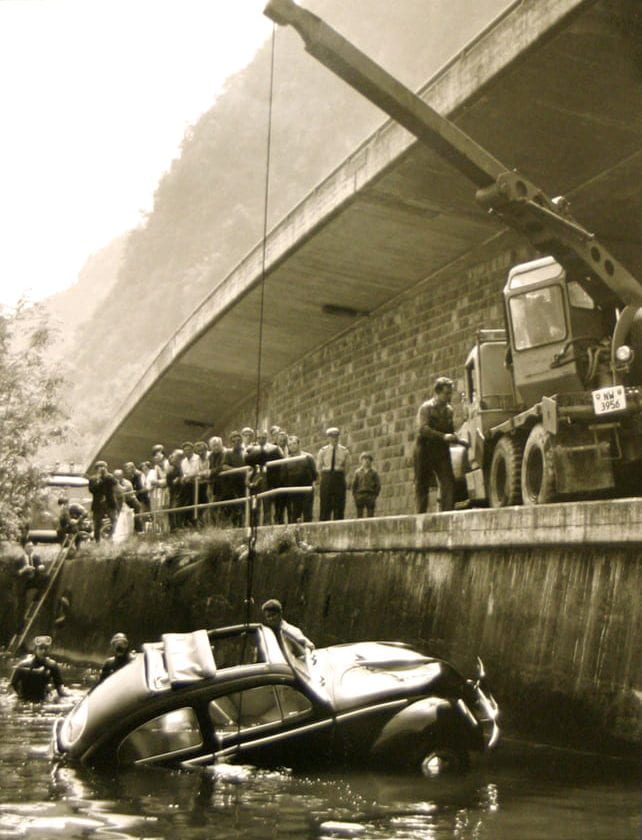

Arnold Odermatt points our view directly to our vulnerability in the face of speed. His black-and-white photographs, like Hergiswil (1968) and Dallenwil (1977), capture the aftermath of motor vehicle accidents. From 1948 to 1990, Odermatt worked in the Swiss canton of Nidwalden as a police photographer and was a pioneer in this undeveloped field. Odermatt empties the image of everything but the forlorn wreck and contrasting picturesque landscape. In Dallenwil, a disfigured white Mercedes is folded around a telephone pole. Like Chamberlain’s sculpture, the metal of the car is contorted and refitted with an almost Cubist effect. The vehicle is situated alongside a bucolic field of flowers, standing in sharp contradiction to the violence of the crash.

In Hergiswil, a submerged black Volkswagen Beetle is shown being lifted out of a lake beneath the Swiss Alps. It resembles a Weegee or Mell Kilpatrick photograph, absent any unaffiliated onlookers. The terraced roadway towers above, mirroring the profile and enormity of the mountains beyond and expressing the sublime power of infrastructure and the speed it facilitates. The pictures cast the car as a memento mori, one that exposes the fragility of steel, glass, us, and our world in the face of automotive speed.

Image credits:

Robert Stanley (American, 1932–1997), Crash, 1966 (Indianapolis 500), 1966. Liquitex on canvas 50 1/8 x 45″. University purchase, Bixby Fund, 1967.

Doug Aitken (American, b. 1968), fury eyes, 1994. Color video with sound, 7:30 min. Gift of Peter Norton, 2015.

Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937), with Mason Williams (American, b. 1938) and Patrick Blackwell, Royal Road Test, 3rd edition, 1971 (first published 1967). Artist’s book: offset printed, 9 7/16 x 6 1/2 x 3/16″. Published by the artist, Los Angeles. Kranzberg Art & Architecture Library, Washington University in St. Louis. © Edward J. Ruscha IV.

John Chamberlain (American, 1927–2011), Hanging Herm, 1974. Painted and chromium-plated steel, 40 x 59 x 25″. Gift of Dr. Eugene Spector, 1976. © John Chamberlain / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Arnold Odermatt (Swiss, b. 1926), Dallenwil, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 5/8, 15 7/8 x 11 7/8″; and Hergiswil, 1968. Gelatin silver print, 7/8, 15 3/4 x 12″. University purchases, Charles H. Yalem Art Fund, 2003.