Cars are objects of desire, tied to personal identity and presented as extensions of the individual. Automobile manufacturers and advertisers pitch cars as the epitome of convenience that increases freedom of mobility and individual autonomy, while American novels, music, and films have glorified them. However, the lure of automobiles is more extensive than its absorption in general culture; cars are among the few material objects around which an entire culture has developed. In the United States, car culture took off in the 1950s through the growth of the car industry and the expansion of vehicle ownership. Car culture developed around hot rods, drag racing, NASCAR, and an ever-growing number of standard cars on the road. During this boom a wide array of buildings dedicated to automobile-centric experiences began to populate the vehicular landscape, including diners, drive-in restaurants and theaters, motels, and roadside attractions.

John Baeder’s screen print Market Diner (1979) presents an example of the everyday automotive environment in the United States. While Market Diner idealizes car culture, its photographic realism also captures aspects of the complicated sociopolitical history that developed around the car. The image oscillates between a nostalgia for the recent past and the grittiness of the lonely paved landscape. Car culture thrives on wistful sentimentality for the open road and classic cars, but in the lived experience of vehicle use, both in the 1950s and now, driving is altogether far less the luxurious adventure that car manufacturers and advertisers sell to the public. Stuck in traffic on a daily commute or working as a taxi driver, the experience of driving is—more often than not—a lonely, time-consuming, and tedious chore.

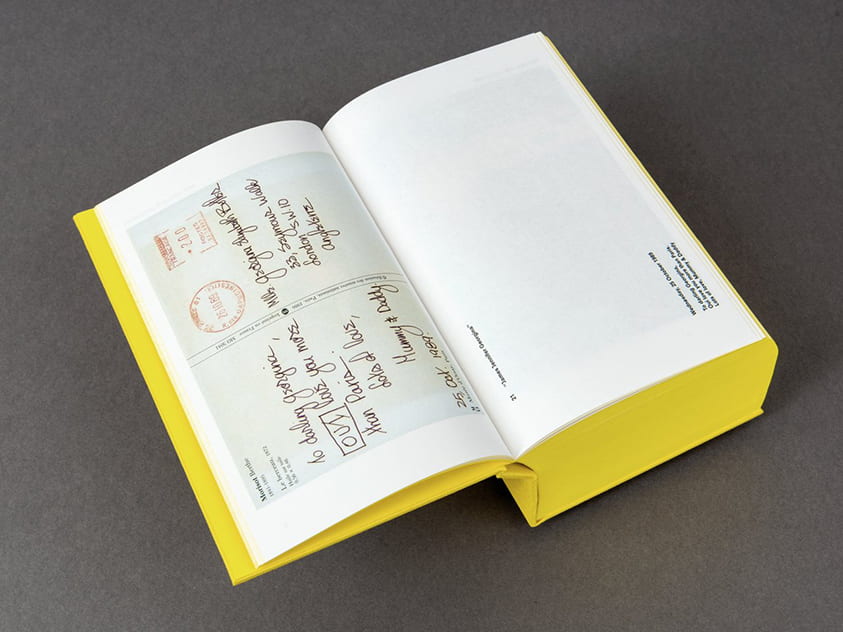

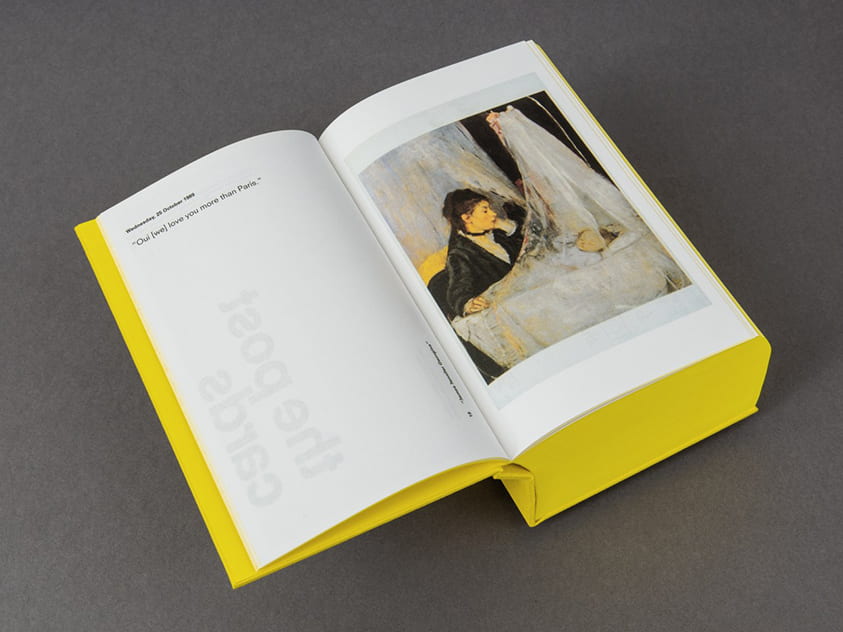

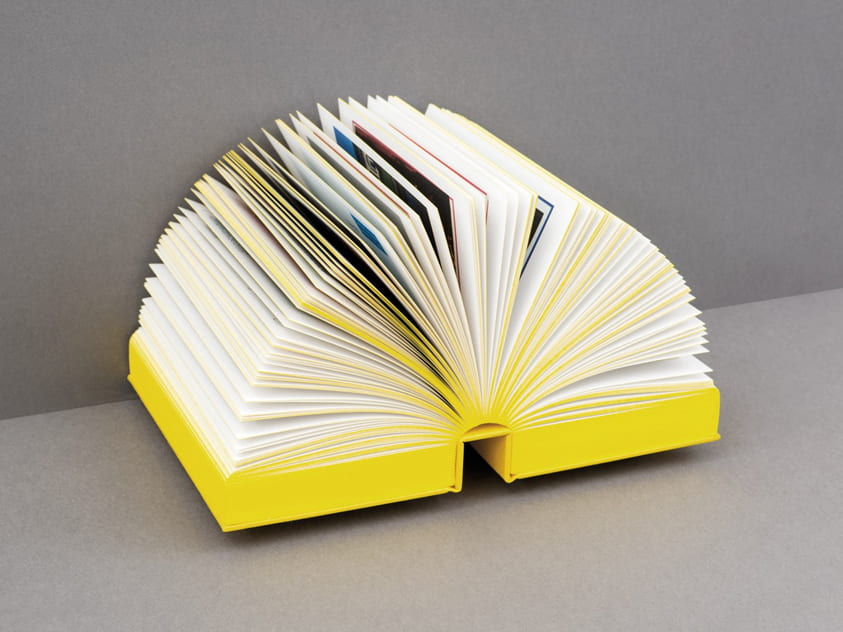

The growth in the automobile’s popularity gave way to another central element of car culture: the great American road trip. As a central part of the American experience in the 1950s, road trips live on as part of present-day culture. One such journey that took place from 1989 to 1990 is portrayed in Irma Boom’s design for the book James Jennifer Georgina (2010). Nearly as thick as it is wide, the yellow monolith fans out into an array of 1,200 pages that document 268,162 miles traveled, including through the reproduction of 1,136 postcards and over a decade of a family’s history. Written along the lines of what might seem to be a classic road trip with an existential quest—akin to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road—the book presents fragments of the complicated tale of one stereotypical American family. In the words of wife and mother Jennifer, her husband James “was drinking himself to death. But he could drive a car from A to B, have a sense of pleasure and not drink—so in an irritable panic, I decided to take him on a road trip to dry him out.”[1] The postcards with motifs of tourism and travel complement and contrast with the social complexities the family faced in parallel to their motion across time and distance.

Image credits:

John Baeder (American, b. 1938), Market Diner, from the portfolio City-Scapes, 1979. Screen print, 247/250, 22 x 30″. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Harold J. Joseph, 1980.

Irma Boom (Dutch, b. 1960), James Jennifer Georgina, 2010. Artist’s book: offset printed, 7 1/2 x 4 7/8 x 3 1/2″. Published by Erasmus Publishing Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom. Kranzberg Art & Architecture Library, Washington University in St. Louis. Photos by Ivan Jones, courtesy of http://jamesjennifergeorgina.com/.