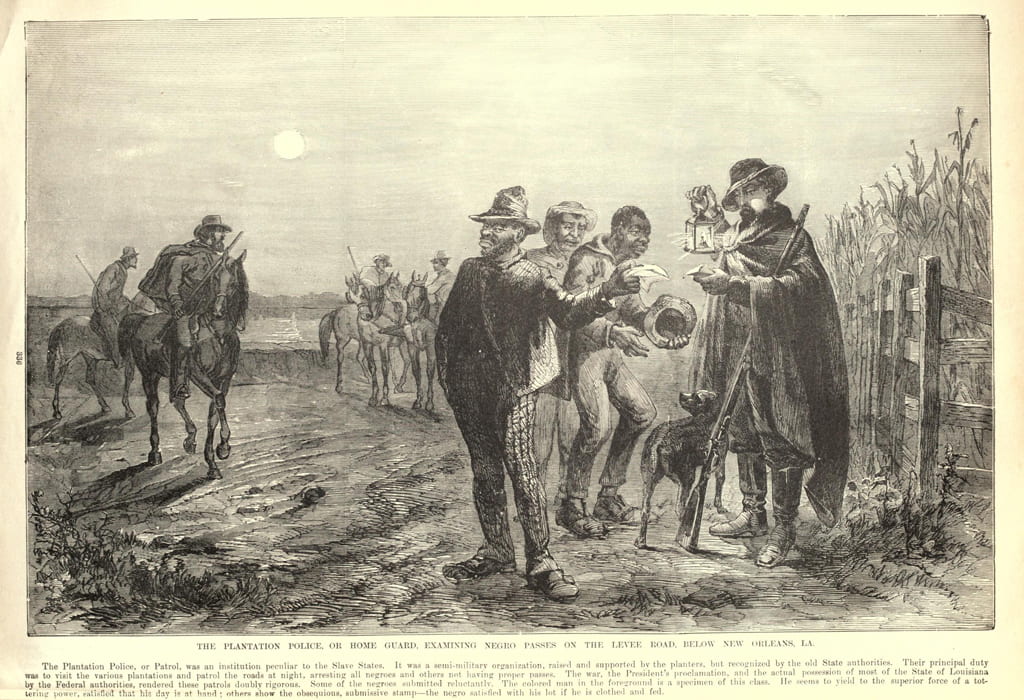

Stationed at the gallery entrance, Frederick B. Schell’s engraving Plantation police, or home-guard examining passes on the road leading to the levee of the Mississippi River (1863) opens a meditation on legacies of enslavement. Tracing the origins of policing in the United States to the crucible of chattel slavery, the image affords a long view of our enduring ordeals of racialized over-policing and under-protection and captures quotidian aspects of racial subjugation. Kara Walker’s Golddigger (with Klaus Bürgel, 2003) and The Bush, Skinny, and De-boning (2002) invoke more intricate and varied instruments of racialized violence and repression, a more general brutalization of our political culture, and the social reproduction of racialized violence in the era of enslavement and its aftermath.

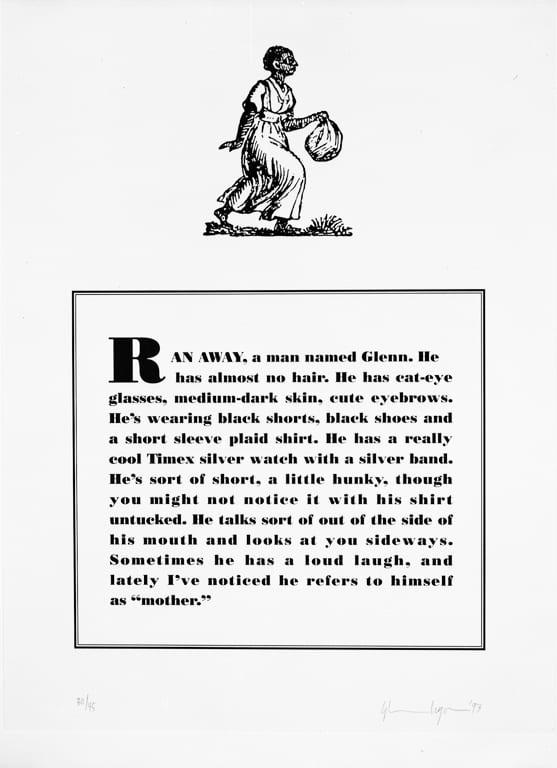

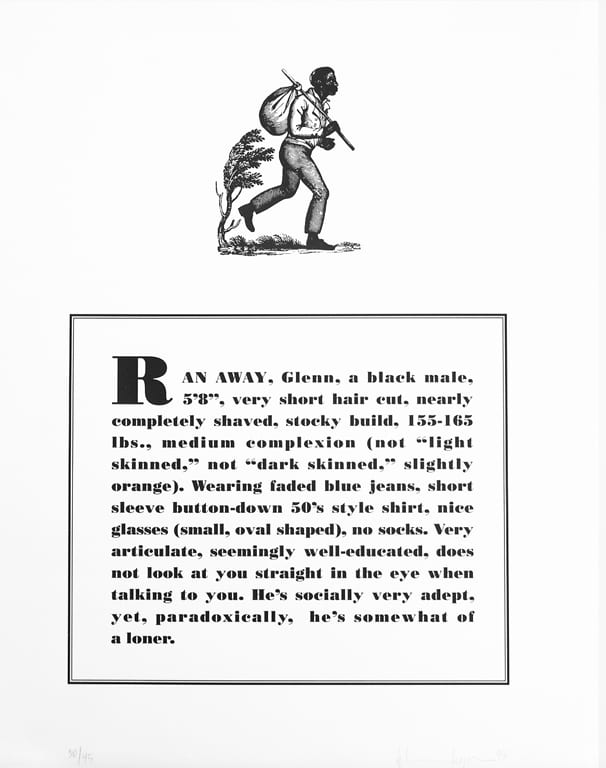

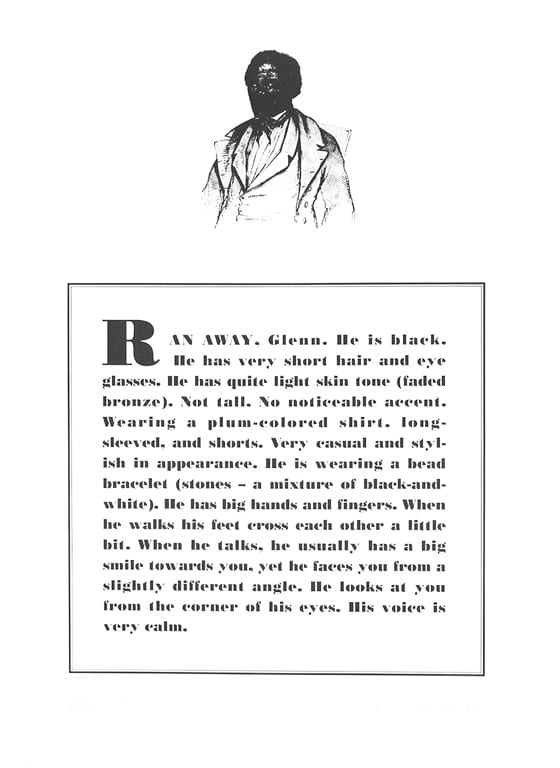

Truths and Reckonings counters the false narrative that settler colonialism, genocide, and enslavement—histories deeply embedded in our nation’s origins—“ended long ago” by charting their wake. Selections from Glenn Ligon’s series Runaways (1993), which employs the format of wanted posters, call to mind a persistence of hyper-surveillance and racialized social control, including their discursive aspects. His textual portraits of a complex black personae contrast with caricatured, flattened renderings more typical of such posters and much mass communication since, including racist discourses of today (such as on “thugs” and “illegals”) that rationalize contradictions of repression and confinement in our alleged “land of the free.”

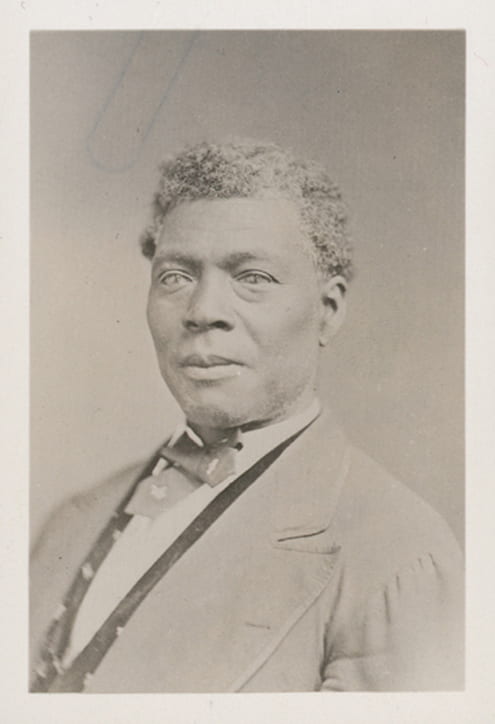

As an intervention in public memory, Truths and Reckonings seeks to unsettle stock notions of American freedom so that liberty might be realized. Just beyond Glenn Ligon’s Runaways are portraits paying respect to Archer Alexander, Missouri’s reputed “last fugitive slave,” who escaped from St. Charles, Missouri, to St. Louis, where he would never actually be free. Aided in escape by Washington University’s founding president, William Greenleaf Eliot Jr., Alexander was nonetheless assaulted by the slave patrol and imprisoned in a St. Louis slave pen. Eliot helped Alexander attain another tenuous liberation shortly before the Emancipation Proclamation made its way to Missouri, freedom’s Compromise State, and commissioned these portraits of Alexander to serve as a model for the formerly enslaved person depicted by Thomas Ball in his memorializing sculpture Emancipation Group (1875). Ball’s rendering of Alexander as an inferior signaled the persistence of white supremacist ideology and the related reign of racist violence—cultural, structural, and direct—in America’s apartheid era (c. 1870s–1960s). Alexander died in 1879, shortly after St. Louis’s mayor pledged to deny sanctuary to destitute southern black migrants fleeing persecution.

Image credits:

Frederick B. Schell (American, d. 1905), Plantation police, or home-guard, examining passes on the road leading to the levee of the Mississippi River, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 11, 1863. Engraving, 9 × 14″ (plate). James E. and Joan Singer Schiele Print Collection, Rare Book Collections, Washington University in St. Louis.

Kara Walker (American, b. 1969) and Klaus Bürgel (German, b. 1958), Golddigger, 2003. 22k gold and mixed media, 2/10, 10 1/16 × 16 × 16″ overall. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, Gift of Peter Norton, 2015.

Kara Walker (American, b. 1969), The Bush, Skinny, and De-boning, from Edition No. 19, 2002. Painted stainless steel in 3 parts, 29/100, 5 3/4 × 5 1/2 × 3/4″, 4 1/2 × 4 1/8 × 3/4″, 5 3/4 × 6 × 3/4″. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, Gift of Peter Norton, 2015.

Glenn Ligon (American, b. 1960), selections from the portfolio Runaways, 1993. Lithographs, 30/45, 16 × 12″ each. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, University purchase, Nathan Cummings Fund and Art Acquisition Fund, 1996.

John A. Scholten Photography Studio, St. Louis, Portraits of Archer Alexander, c. 1870-71. Black-and-white photographs, 4 1⁄4 × 2 1⁄2″ and 4 × 2 1⁄2″. William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers, University Archives, Washington University in St. Louis.