Research in our lab focuses on two basic questions in developmental biology:

- How do precursor cells divide asymmetrically to produce daughter cells of distinct fates

- How do individual cells execute cell-type specific differentiation programs?

We investigate the genetic and molecular basis of both asymmetric divisions and cell-type specific differentiation programs through the use of the Drosophila model system, focusing primarily on nervous system development.

Assymetric Cell Division:

Asymmetric division – the process through which a precursor cell divides to produce two daughter cells of distinct fates – is a basic mechanism used throughout the animal and plant kingdoms to create cell-type diversity. In flies, mice, and almost certainly man the integrated activities of the Notch signaling pathway and the intrinsic cell fate determinant Numb regulate the asymmetric division of many precursors in multiple tissues. Notch/Numb-mediated asymmetric divisions result in daughter cells of distinct fates due to differences in the amplitude of Notch signaling activity between the two daughter cells. One daughter cell exhibits high-levels of Notch signaling, which triggers this cell to adopt a specific fate, termed the “A” cell fate. The other daughter cell exhibits low-levels of Notch signaling, and this cell adopts an alternate fate, termed the “B” cell fate.

How do the two daughter cells come to exhibit such different levels of Notch signaling activity? Upon precursor division, Numb segregates exclusively into the “B” daughter cell, where it functions to inhibit the reception and/or transmission of Notch signaling. Thus, the presence of Numb ensures that Notch signaling is kept low in this cell, and as a result this cell adopts the “B” fate. Conversely, the absence of Numb in the “A” cell permits high-level Notch signaling in this cell, which induces this cell to adopt the “A” fate. Both daughter cells express Notch and can respond to Delta signaling, as in the absence of Numb both daughter cells adopt the Notch-dependent “A” fate. Thus, the asymmetric segregation of Numb into one of two daughter cells is critical to the faithful execution of asymmetric divisions.

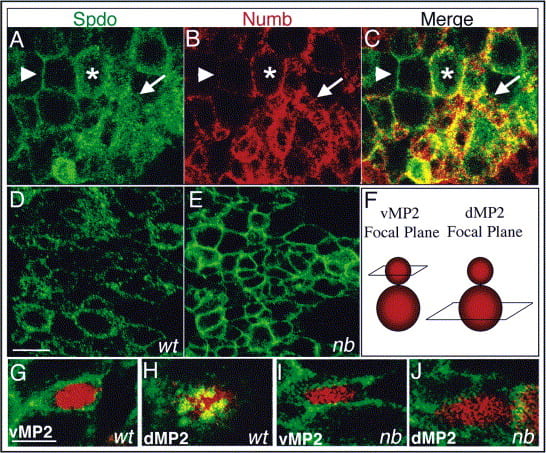

But, how does Numb inhibit Notch signaling? This question gains interest when one considers that the Notch signaling pathway regulates a myriad of developmental events and cells involved in executing each of these events express both Notch and Numb, however loss of function studies reveal that Numb normally only inhibits Notch signaling during asymmetric divisions. Work from our lab suggests that the answer to this question, at least in flies, revolves around Sanpodo – a four-transmembrane protein. Sanpodo is expressed exclusively in asymmetrically dividing cells and is necessary for productive Notch signaling in the “A” cell during asymmetric divisions, in accord with the limited expression profile of Sanpodo no other Notch-dependent event requires spdo function for its execution. Our genetic studies have shown that Sanpodo exerts opposite effects on Notch signaling in a context-dependent manner: in the absence of Numb, as occurs in the “A” cell, we have found that Sanpodo potentiates Notch signaling activity; in contrast, in the presence of Numb, as occurs in the “B” cell, Sanpodo enables Numb to inhibit Notch signaling activity. Numb appears to mediate its effect on Notch signaling by regulating the subcellular localization of Sanpodo, as in the absence of Numb Sanpodo preferentially localizes to the cell membrane, whereas in its presence Sanpodo preferentially localizes to cytoplasmic vesicles. Present work in the lab focuses on identifying the mechanistic basis through which Sanpodo both promotes and inhibits Notch signaling activity depending on context via the identification of factors that associate with Sanpodo.

Cell-type Specific Differentiation:

Asymmetric divisions ensure that daughter cells adopt distinct fates, however downstream events are crucial to enable each sibling cell to manifest the appropriate anatomical and physiological features. While all tissues and organs are comprised of many different types and subtypes of cells, the nervous system takes cell-type diversity to the greatest extreme with thousands of morphologically and physiologically distinct cells contained within this tissue. Work from many labs over the past 10-15 years has revealed that a large set of transcription factors act in a combinatorial manner in post-mitotic neurons to direct individual or small groups of lineally-related cells down specific paths of differentiation. Many members of this group of transcription factors – such as Hb9, Nkx6, Dbx, Lim3, and Islet – appear to carry out similar, thought not identical functions, in the Drosophila and mammalian CNS.

Our lab has focused on characterizing the function of the homeodomain-containing transcription factors Hb9, Nkx6 and Dbx during CNS development in flies. Hb9 and Nkx6 function in a largely redundant manner to promote the differentiation of a particular subset of motor neurons: those that project to ventral and lateral body wall muscles. In contrast, Dbx functions in the sibling interneurons of many of these motor neurons to regulate the development of these cells. Importantly, cross-repressive interactions between Hb9/Nkx6 and Dbx appear to play key roles in ensuring that sibling pairs of Hb9/Nkx6+ motor neurons and Dbx+ interneurons retain their distinct differentiated phenotypes. While we are continuing to characterize the expression and function of additional transcriptional factors that control neuronal differentiation and to identify downstream targets of these transcription factors, we have also found that many of these transcription factors are expressed in distinct subsets of neurons throughout the life of a fly. Thus, in the future, we would also like to explore how these transcription factors, and the neurons in which they are expressed, govern the ability of the organism to sense and to respond to changing environmental and physiological conditions through modifications to both the overt behavior of the fly as well as its physiology.