If a Missouri snake is venomous:

- It is in the pit viper family – it will have a distinguishable pit between each eye and nostril. These pits, sometimes referred to as loreal pits or fossa, are used as infrared-detecting organs, allowing the viper to sense its prey.

- Its pupils will be vertical slits.

- It will have a single row of scales along its underside.

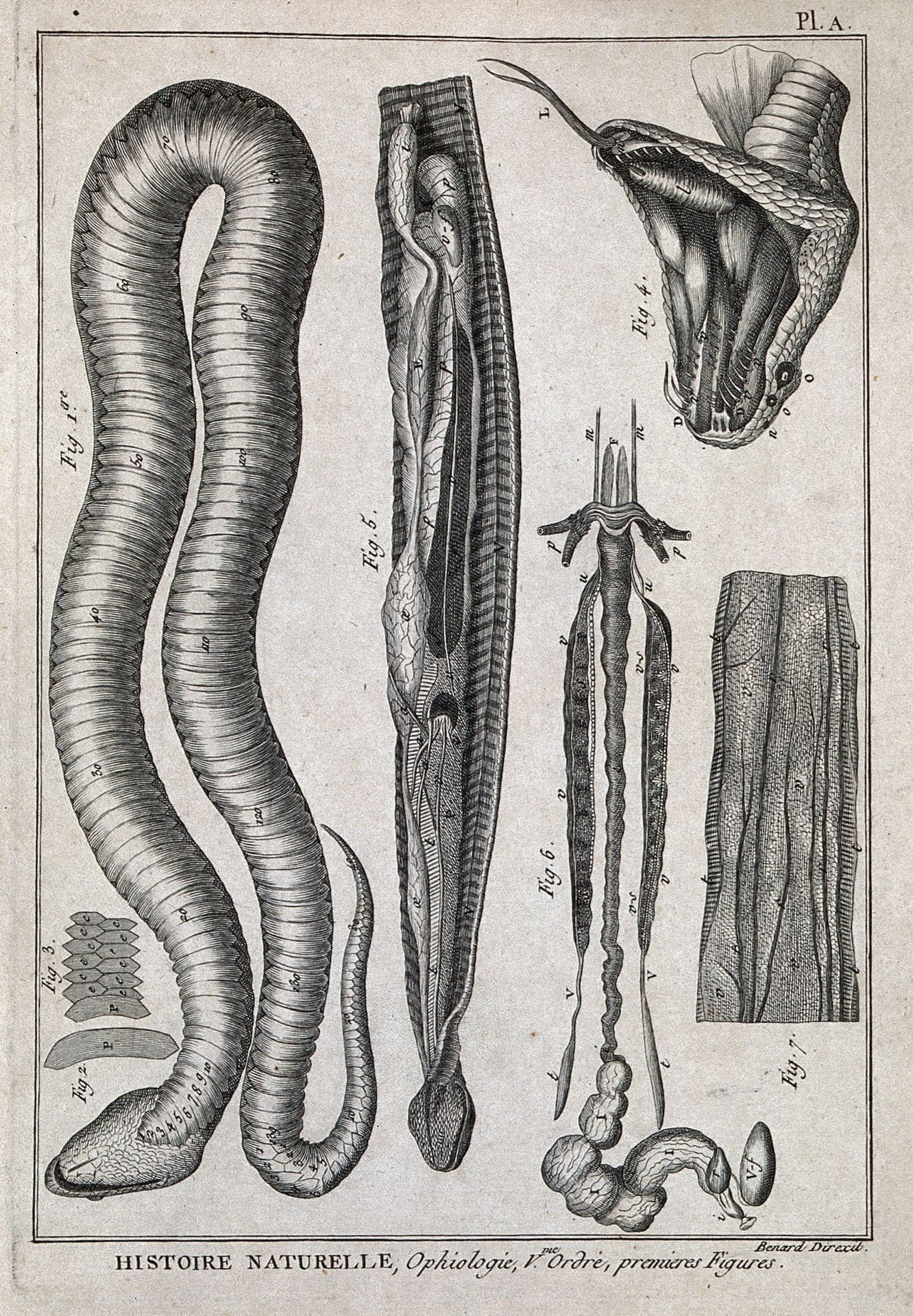

Snake anatomy engraving (1778). Iconographic Collections. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Snake head structures. Comparative Zoology, Structural and Systematic. Orton, Birge (1883). Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A. Non-venomous snake head.

B. Venomous snake heads. Top-right is in the pit viper family – note the slit-like pupils and the indentation between each eye and nostril.

Species of Venomous Snakes

American Moccasins

Genus Agkistrodon. They have keeled scales and an undivided cloacal.

Eastern Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)

By Peter Paplanus CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/2ndpeter/29324851667/in/photolist-2g72GLt-LFkwJP-ajNTpV-ajRGud-ajNTMH-Sv1Zkh-RMhChH-885opH-bTbYXF-8tMyy7-8tJvQn-S4K9jD-5YDCqf-F5S6b-7p1wWv-9AYniM-a9Vb5v/

The Eastern Copperhead can be found across the entire southeastern United States reaching north to Connecticut and New York State. They are found across the whole state of Missouri. They are 61-90 cm in length. Individuals can be pink, tan, grey, or brown with a coppery red head. The dorsal side has distinct brown crossbands with dark borders. These bands are often hourglass shaped with the narrowest portion being on the middorsal section of the snake. The ventral side is white or pale tan with black markings. They can be found in hilly forests or near swamps. One distinct feature is the forked tongue which allows the snake to gather sensory information and strike prey based on a temperature difference.

Osage Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix phaeogaster)

Osage Copperhead. Photo by: Tad Arensmeier, 2007. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Adult Copperheads range between 2-3 feet in length and tend to be active between April and November, in the northern part of Missouri. They can be found in wetlands and on rocky, forested hillsides, and they normally eat small creatures, such as mice, insects, small birds, lizards, etc. Their colors range between a blackish-brown and a light tan color, with darker crossbands that often serve as camouflage, making Copperheads difficult to spot – especially when curled up in dead leaves.

Western Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma)

Western cottonmouth. Photo by: Steve Shively, Photo courtesy of USDA Forest Service

Western Cottonmouth (Yinan Chen, 2014)

The length of a full-grown Cottonmouth can vary between 30 and 42 inches. Cottonmouths are found primarily in southeasten Missouri, and are most active between April and October. As aquatic snakes, they prefer marshy, braskish waters, and eat primarily fish. However, they also eat frogs, lizards, rodents, and other small creatures. Many harmless water snakes are often mistaken for Cottonmouths. Therefore, it is important to note that cottonmouths can be distinguished by their black body, or dark brown body with black bands. Juvenule Cottonmouths have a yellow-green tail which they use to lure prey When threatened, a Cottonmouth will open its mouth to reveal a cotton-white lining, which is where it gets its namesake.

Northern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

By Cabo Neri CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/expeleosierra/14159856172/in/photolist-nzfXVf-hw4nc-hw9rL-778ic3-778jW5-3uAC1k-3uAC1i-3uABZP-3uAC16-o4vhy8-72NW6j-6MCM7u-734S8J-72NW6d-P13uGj-734S5N-3ibiEu-34gF7D-2LJP2A-2Ao77Y-9xHkPP-QTgUPH-TX7NE5-9Ejb2F-GmKTKy-onKNRv-onKQvH-3KJJjB-3KJJjz-483zv9-3ibiEA-3Efe46-aueX7D-483zv7-aozjEa-47sRSS-a5VNNj-8JsWEx-9xHbY6-a5SXZc-9u3pSX-72ZTRR-rbMZZr-8Jw1Ld-9En67h-72ZTXz-QFPbo6-NrC87-afnZXR-RQWZEn

This snake can be found in much of the southeastern United States, including the southeastern tip of Missouri. It ranges from 76-122 cm in length. The Northern Cottonmouth can be olive, brown, or black with crossbands of varying intensities. In youth an individual will have a very patterned head but the pattern fades when the snake reaches maturity. They have a lighter colored ventral side. Cottonmouth snakes will vibrate their tales when excited, a distinguishing characteristic of this species. Cottonmouths are often confused with nonvenomous water snakes but can be separated by traits such as the tail vibration. They are found in moist environments such as swamps, floodplains, streams, beach areas, or brooks.

Rattlesnakes

Rattlesnakes include genera Crotalus and Sistrurus and are only found in the Western Hemisphere from Canada to Argentina. Their scales are keeled and their cloacal is undivided. Rattlesnakes are often recognized by the sound they make with the rattle part of the tale. The rattle consists of interlocking segments that strike against each other to create vibrations which omit the distinct sound.

Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

Timber rattlesnake. Photo by: David Arbour. Photo courtesy of USDA Forest Service

By Peter Paplanus CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/2ndpeter/31140366037/in/photolist-2hdhbjt-PrLvUH-ZQq1VC-YjNJaP-258sDwB-S6dSNr-Yxyf3V-26KUeot-foqXDe-TovZXU-uFT6T8-GqzWwv-oveUGi-oyRQAk-WSQHqb-Hr943W-RGff8s-ootSaq-wFKQHg-86kv3J-29uqVo4-86kv7G-eANoh-bqwUtk-8EAUoe-sscPsz-rKCMqh-nxGHqG-2gey29z-eNZ5HY-4McKLS-21DShVx-B6w3N-5sDmd1-5sDch7-eG8wM-EwwDop-5ozh93-rcFeqx-6SFbLt-aVqsEB-9WNkXX-9WNmhp-P93gJk-XcPJVe-NrHjPY-9WNmVX-9WNn5g-9WNmKX-9WRcEW/

The Timber Rattlesnake can be found in almost every state in the eastern half of the United States, including most of east and central Missouri. It is the largest venomous snake in Missouri, spanning up to five feet in length. Its diet is not limited to small creatures – it eats lizards and rodents, but it can also eat rabbits and other larger mammals. It is a bright tan color with brown v-shaped spots that become bands near the tail, and it has a huge rattle at the end of its tail that serves as a defense mechanism. Timber Rattlesnakes are most active between April and October, and they are nocturnal during the summer. Found in the wooded forests or near river bottoms of Missouri, they could once exist statewide, but now their numbers are declining due to habitat loss.

Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus)

Massasauga rattlesnake. Photo by Tom R. Johnson, Photo courtesy of the Missouri Department of Conservation.

By Charles Peterson CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/petechar/28689806787/in/photolist-H1GZUJ-KHdL2a-QEzr3P-2gpWJ2w-Tk5cY4-7X7jkV-XGdiJz-R5MXYT-7X7jqr-26BC7U9-WuRn6T-VYXdXo-HWxpLP-HTvd1s-53vo2M-aVqiXD-M9YuqH-8qU2po-WhfdXh-fyW7bq-VkGxNK-4Jmt5U-KaD5qY-4Jhfxz-oUpVkM-7LBWoA-8TUtFq-HDxfpY-yG6MzK-9xfHgU-9ZiVPV-24GrzTN-G8imaR-3hhnUD-8uDYuW-5iH9D2-EzRt24/

The Eastern Massasauga can be found in the northern parts of Midwest states, ranging from Wisconsin to southern Illinois, including several places in eastern Missouri. Grassy wetlands are home for the reclusive, non-aggressive Massasauga Rattlesnake. This snake eats primarily rodents and other small snakes, and measures between 18 and 30 inches long. Located sparsely within the northern areas of Missouri, Massasaugas have a thick, dark gray or gray-brown body, with darker, geometrically-shaped spots. They prefer wet, marshy habitats, uncluding bogs and river bottom forests. The current number of Massasaugas is dwindling, but efforts put into marsh restoration would help to ensure the species’ survival.

Western Pygmy Rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius streckeri)

Western Pygmy Rattlesnake. Photo by Smart Glen, courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Services.

The Western Pygmy Rattlesnake is one of the smalles species of rattlesnakes in North America – only 15 to 20 inches long – but it can pack a punch just like its fellow vipers. Western Pygmy Rattlesnakes will eat any small creature, including other small snakes. They are found in semi-shaded hillsides along the southern border of Missouri, and in the Ozarks and St. Francois Mountains, and tend to be active between mid-April and October. A Western Pygmy Rattlesnake will be easier to spot in the wild, due to its heavy contrast in coloring: a light brown body with brown and black spots. Its tail, of course, has a tiny rattle that it uses when threatened.

First Aid

Venomous snake bites are highly unlikely to be fatal – in Missouri, there have only been two documented deaths due to venomous snake bites. That being said, proper medical care is essential in the unlikely event of a snake bite. If you are bitten by a venomous snake, there are important measures you must take quickly in order to prevent further tissue damage.

DO:

- Check surroundings – ensure that they are safe.

- Call 9-1-1, or another emergency telephone number.

- Wash the bite.

- Keep injured area below your heart to prevent venom from spreading quicker.

There are many myths surrounding the treatment of snakebites. Some of these myths could potentially worsen your condition. Therefore,

DO NOT:

- Cut the wound.

- Apply a tourniquet.

- Apply ice to the wound.

- Apply suction of any kind (especially not your mouth).

The best way to treat a snake bite is to not get bitten at all. Wear closed-toed shoes when hiking, and always be aware of your surroundings. Remember: snakes are afraid of humans, and would rather be left alone – they will not attack you unless they are provoked. Remember that while you are exploring Missouri’s wilderness, you are also sharing it – so treat all wild creatures with respect.

For more information on how to treat snake bites, please refer to page 10 of this emergency reference guide published by American Red Cross.

Benefits of snake venom

Although poisonous snake venom is harmful or even deadly to humans, it can be harnessed for positive uses in many medical treatments. Early research into using snake venom as a cancer drug yielded many positive results in animals, including destroying tumor cells in rats. Lectin proteins have been successfully isolated from snake venom and incorporated in cancer medicines. Snake venom as a toxin has also been shown to slow the process of apoptosis, which is the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells leading to the growth of tumors. There is still more research to be done but the incorporation of snake venom into cancer drugs is promising.1

Scientific Research

Osage Copperheads

A study conducted in 2015 investigated the levels of blood coagulation after copperhead bites. Normally routine tests are conducted after snake bites to determine whether the levels of blood coagulation due to envenomation pose a threat to the patient. Blood coagulation is common after rattlesnake bites, but less so for copperheads. This study was conducted in order to determine if the levels of blood coagulation after copperhead bites were abnormal and/or unsafe enough to justify routine blood tests. After investigating the charts of 106 children admitted to the St. Louis Children’s Hospital for identifiable or probable copperhead bites, the researchers determined that the majority of those admitted fell within normal blood coagulation levels, and those that were abmormal were likely due to initial snake misidentifiation by the patient. This study showed that multiple routine blood tests (as is procedure for rattlesnake bites, for instance) may not be necessary if the bite is from a copperhead and bleeding is not clinically apparent.

Ali, Anah J., David A. Horwitz, and Michael E. Mullins (2015). “Lack of Coagulopathy after Copperhead Snakebites.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, 65.4, 404-409.

Timber Rattlesnakes

A restored Missouri glade (2013). Young Conservation Area.

The systematic destruction of mature, closed-canopy forests poses a major threat to nearly all species that inhabit those forests, including venomous snakes. However, there have been few studies on snakes that inhabit already anthropogenically disturbed habitats. A study conducted in 2009 at the University of Arkansas focused on a timber rattlesnake population in west-central Missouri, an already fragmented, agricultural environment, in order to determine the individual growth rates, foraging behavior, life cycles, and other ecological and behavioral determinants of the health within that particular population, and in a broader sense, understand what these reptiles need to survive in fragmented landscapes. The data from the study showed that the snakes in preexisting fragmented landscapes had stable growth rates, and were able to forage around the perimeters of the exposed areas. These results showed that timber rattlesnakes may not, in fact, need dense, closed-canopied forest to survive, as long as their dietary and thermal needs are still met. We can use these results to rethink the conservation efforts put towards preserving timber rattlesnake populations – that preserving the population densities of the snake’s small-rodent prey may be a more species-specific and effective strategy than broadly restricting the deforestation of closed-canopy habitats.

Whittenberg, Rodney D (2009). “A Study of the Timber Rattlesnake in a Fragmented Agricultural Landscape.” Dissertations & Theses – Gradworks.

Massasauga Rattlesnakes

Massasaugas prefer wet habitats, but how much water is too much water? In 1993, the northern region of Missouri experienced its largest flood in over 100 years. This flood greatly effected the ecosystems in northern Missouri – areas where Massasauga rattlesnakes can be found. The damage from the flood greatly affected the sparse Massasauga population of Northern Missouri. In order to further investigate the effects of the flood, a longitudinal study between 1993 and 1995 was conducted, looking at the population density of these rattlesnakes before and after the flood (and matching the methods of the study conducted in 1986, before the flood, as closely as possible) Due to the dramatic loss of prey and habitable regions, the researchers also monitered the rate of recovery, reproductive characteristics, and changes in body condition of the snakes. The researchers found that following the flood, the overall abundance of Massasauga rattlesnakes did not change dramatically. However, the relative abundance of small Massasaugas greatly decreased, having likely been wiped out by the force of the flood. Although overall there were more larger snakes, the snakes weighed less relative to their size when compared to the data from 1986 This was likely due to decreased availability of small prey – a result of the flood. In addition, the sex distribution shifted in favor of males post-flood, likely due to the smaller size of females, and as a result, overall reproductive rates decreased. The population of Massasaugas was greatly weakened by the flood, but follow-up data collection in 1996 showed that fortunately both the ecosystem and the rattlesnake population were recovering from the flood. This study showed not only the importance of monitering the recovery and overall abundance of individuals within populations after habitat destruction, but also the more subtle effects within populations that habitat destruction can put already endangered species into even greater danger of extinction.

Seigel, Richard A., Christopher A. Sheil, and J. Sean Doody (1998). “Changes in a Population of an Endangered Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus) Following a Severe Flood. Biological Conservation, 83.2, 127-131.

Sources:

1Li, Li et al. “Snake Venoms in Cancer Therapy: Past, Present and Future.” Toxins vol. 10,9 346. 29 Aug. 2018, doi:10.3390/toxins10090346

“Snakes.” Missouri Department of Conservation. Conservation Commission of Missouri, 2015. Web. 9 October 2015.

Collins, Joseph and Roger Conant. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. 3rd. ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998. Print.

Babysitting Emergency Reference Guide. American Red Cross.