Dark Eyed Junco

Junco hyemalis

Taxonomy:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

Species Description:

Identifying Traits:

Dark Eyed Junco’s are small birds, with wingspans of 7.1-9.8 inches

(18-25cm) and body lengths of 5.5-6.3 inches (14-16cm)5. They are divided between male and female colorations, with males having a dark grey upper body, head, and neck with a lighter gray underbelly and females having a tan brown upper body, head, and neck with a white underbelly. The legs of both genders are a pale brown color. Both genders posses characteristically dark eyes. There beaks tend to be a pale brown-pink but there are some small reported sightings with brighter beak coloration, such as orange and yellow.

Behavior:

Dark Eyed Junco’s organize themselves both by pairings and by flocks. The pairings occur alongside mating in the spring and summer months, while flocks tend to form as these birds vie for limited resources in the late autumn and winter. The adult males of the flock dominate the feeding hierarchy and can force the lowest members, the young females, to starve7. They fly together around sunrise and sunset and spend daylight hours foraging individually. Within the winter range, it is common to find a greater number of males nearer to the breeding grounds for the following spring, which gives the males an advantage in establishing themselves.

Life History:

Diet:

Dark Eyed Junco’s diet varies depending upon the season and location. The are omnivores, capable of eating spiders and insects during the spring and summer months as well as grass seeds and small fruits during the autumn and winter months. However, they tend to favor seeds and plants over insects5, consuming approximately three times the quantity of seeds and plant material to insects and spiders. Burrowing into shallow soils and through thin layers of snow is common, especially when targeting grubs and caterpillars.

Reproduction:

Dark Eyed Junco’s have very characteristic reproductive habits. Generally starting in the spring, Males will migrate into a territory in advance of the females and begin singing from the tallest available tree in the immediate area (approximately 2-3 acres). When the females arrive, the males will try to persuade a female of the species with bird song and with displays involving his tail5.

Once paired, they will together build a nest on the ground or no more than 8 feet above the ground that will often be used for two or more broods in a season3. Dark Eyed Junco couples produce between 3-6 eggs, ranging in color from white to pale green. The chicks take between 10-14 days to develop enough to leave the nest, though they are dependant on parental feeding for three more weeks2. Dark Eyed Junco’s are noted to have a relatively high survivability and can live between 3-11 years.

Habitat

Due to their tendency to nest on or right above the ground, Dark Eyed Junco’s are commonly found in woodland areas with openings in the forest and a diverse, herbaceous understory. They prefer the edges of large forestlands, clearings, meadows, and streams. They avoid dense forest and as such are frequently found in disturbed areas and close to human areas. This less dense habitat makes them easier prey for hawks, owls, and shrikes as well as ground mammals such as cats who frequently raid their ground nests for eggs.

Distribution

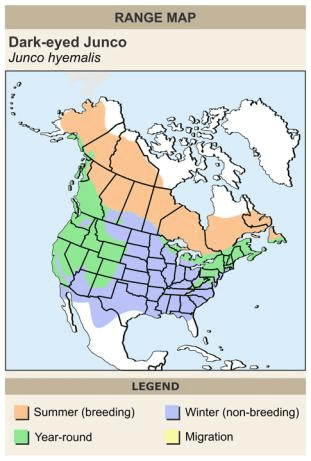

Dark Eyed Junco’s are found across the country and tend to summer in Canada and the northern United States and migrate south for the winter towards the northern Gulf of Mexico and southern United States. There are many groups of Dark Eyed Juncos who do not migrate, especially those found in Midwestern and Eastern states that have moderate continental climates. The map of their North American range is shown in the maps section (Figure 1), with a map of Missouri alongside it (Figure 2). Missouri is located within the winter range of the bird and is noted as being a common viewing region for Dark Eyed Junco migrations and flocking 4.

Research

Dark Eyed Juncos, with their wide distribution and proximity to humans, are a frequently studied species, especially their social habits. One of the most interesting studies about the Junco hyemalis was conducted by Thomas Allen, a professor at Michigan Technological University. The study is more of an account of the behavior of a male Dark Eyed Juncos when he replaced a dead male in a family1.

Replacement parental behavior in the animal kingdom is extremely varied, with many species acting like gorillas and killing off the former male’s children when taking over a family. This is done to increase the new male’s relative fitness, or likelihood of success in reproduction. The Dark Eyed Junco male that the study focused on acted very differently towards the offspring of the dead male. The new male entered the territorial range of the dead male and began moving towards the nest, distracting the female and coercing her to spend time with him. Despite the fact that she was already raising a brood, she copulated with the new male and he began providing food for her and the young, even though they were not his own. It took four days for the new male to begin feeding the children that were not his own. He also played a large part in watching over the nest and defending the nest, even before he began feeding the offspring.

Overall, behavior like this is considered maladaptive in that it decreases the new males chance of successfully raising his own children. Birds have been documented as ignoring the young that are not their own, offering “little to no parental assistance6.” Since this research is based off of a single coupling, we cannot assume the behavior holds through. Despite this, the research raises many interesting questions about replacement parental care and its implications for other populations.

Notes: The species was first named by Carolus Linneaus in 1758 but was later revised by the scientific community. The name translates as “Winter Junco”.

Distribution Map

Sources and Relevance:

Allan, Thomas A. “Parental Behavior of a Replacement Male Dark-Eyed Junco.” The Auk , 1979;96:630-631. → This research focuses on the behavior of replacement males in relation to the widowed female and the offspring of the deceased male.

Bent, Arthur C. Life Histories of North American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and Allies: Part II. New York: Dover Publications. 1968. → This article was essential for gathering the data necessary to assemble a life table for the Dark Eyed Junco.

Ferree, Elise D. “White Tail Plumage and Brood Sex Ratio in Dark-Eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis turhberi).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2007;62:109-117 → This study highlighted the important points of the reproductive process in Dark Eyed Juncos.

Holberton, Rebecca L. “An Endogenous Basis for Differential Migration in the Dark-Eyed Junco”. The Condor , 1993;95:580-587 → Holberton is a vital source of evidence for the distribution and migratory behavior of the Dark Eyed Junco

Nolan, V., Jr., E.D. Ketterson, D.A. Cristol, C.M. Rogers, E.D. Clotfelter, R.C. Titus, S.J. Schoech, and E. Snajdr, “Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis).” The Birds of North America, 2002; 716: 334-338. → Nolan et al. provided important background information and physical description for the Dark Eyed Junco.

Power, Harry W. “Mountain Bluebirds: Experimental Evidence Against Altruism.” Science , New Series, 1975;189:142-143. → Power’s study was a crucial counterpoint to the behavior observed in the Allan study

Rogers, C.M., Nolan, V. Jr.. and Ketterson, E.D. “Winter Fattening in the Dark-Eyed Junco: Plasticity and Possible Interaction with Migration Trade-Offs.” Oecologia 1994; 97: 526-532. Web. → Rogers’ research supplemented insights into the social stratification behavior and flocking of Dark Eyed Juncos in the winter.

Image:

Field Guide to Birds of North America. Dark-eyed Junco. Mitch Waite Group. 2010. Web. 25 Oct. 2013.