In the Gilded Age the lure of international markets produced a groundswell of support in the US for the building of a Central American canal under the oversight and control of the federal government. Constructed between 1904 and 1914, the Panama Canal was designed to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and ensure the nation’s dominance in global trade.

The American printmaker Joseph Pennell traveled to Panama by steamer in 1912, commissioned by The Century Magazine and The Illustrated London News to chronicle the closing stages of the canal’s creation. As Pennell’s ship approached the isthmus, he saw misty valleys that reminded him of central Italy, high peaks “strange yet familiar” from Japanese prints, and quaint villages “reminiscent of Spain.”[68] His international vision of Panama expressed Americans’ optimism that finishing the canal would complete the country’s expansion into a global empire.

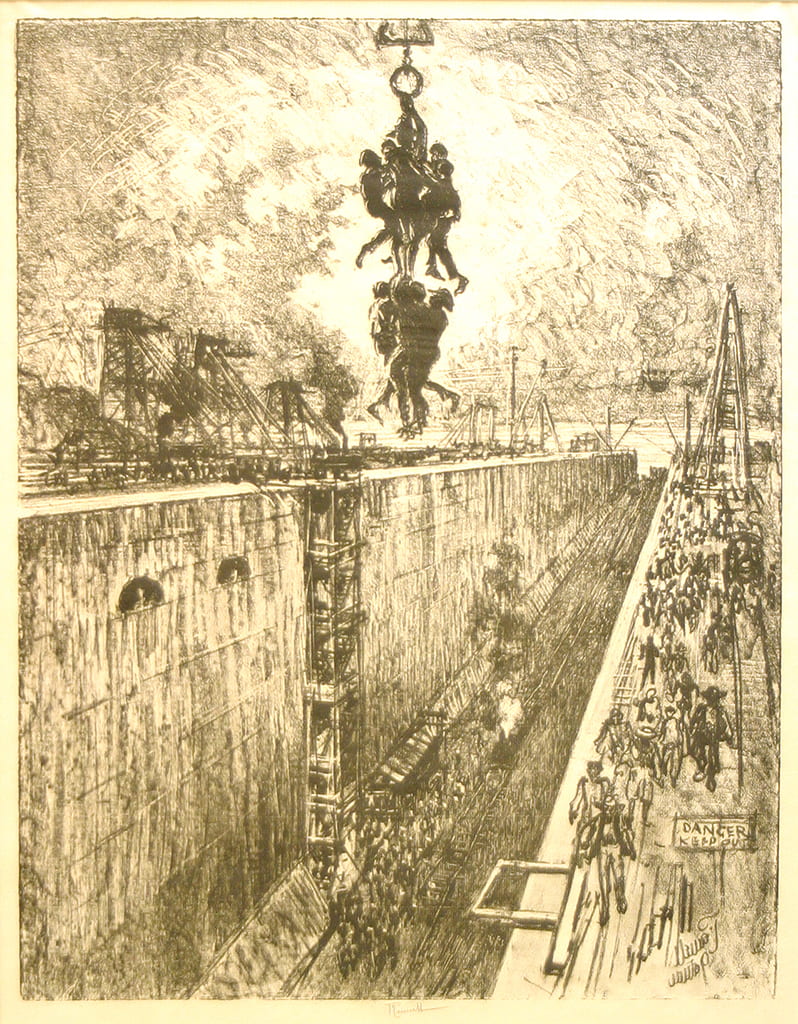

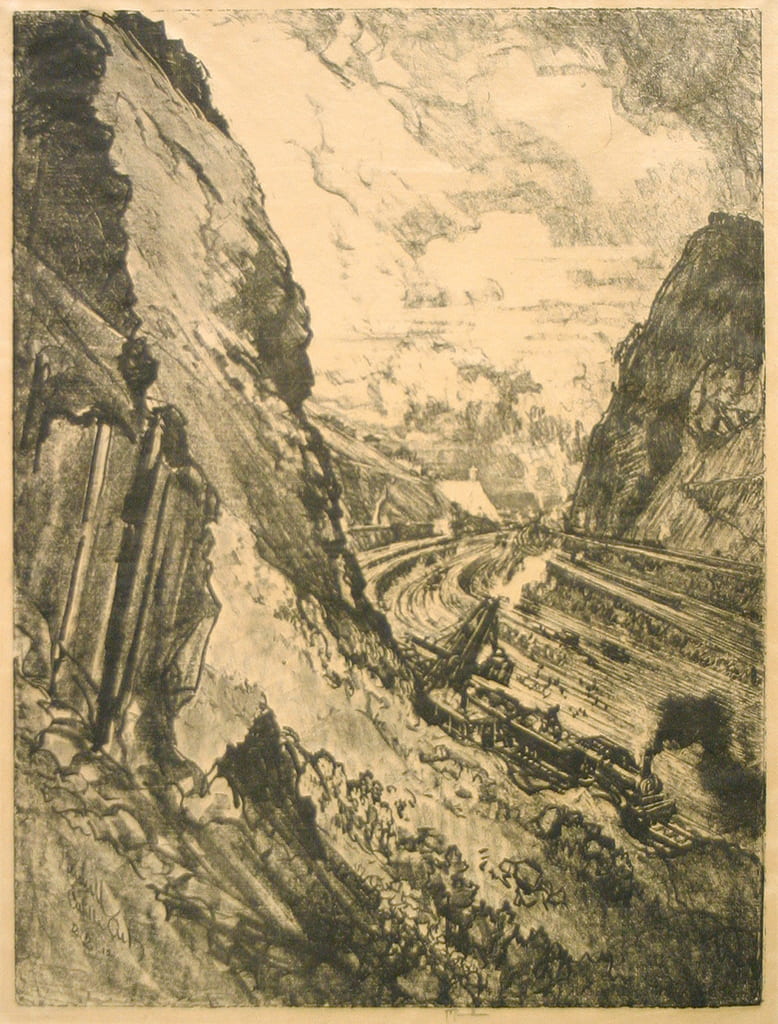

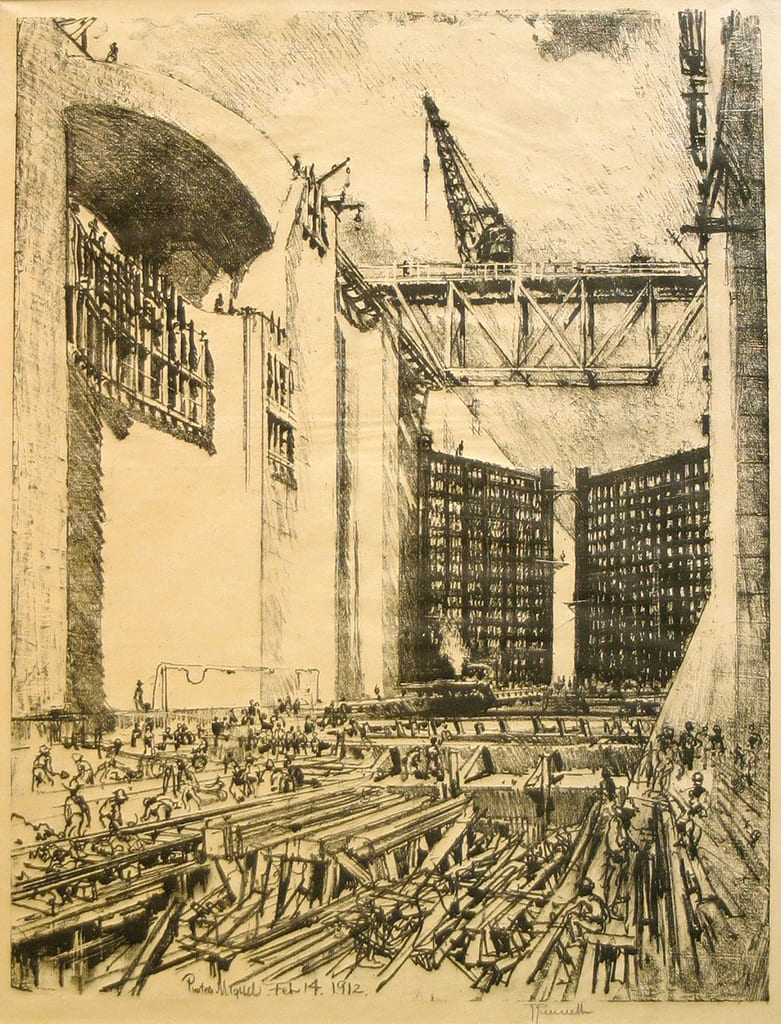

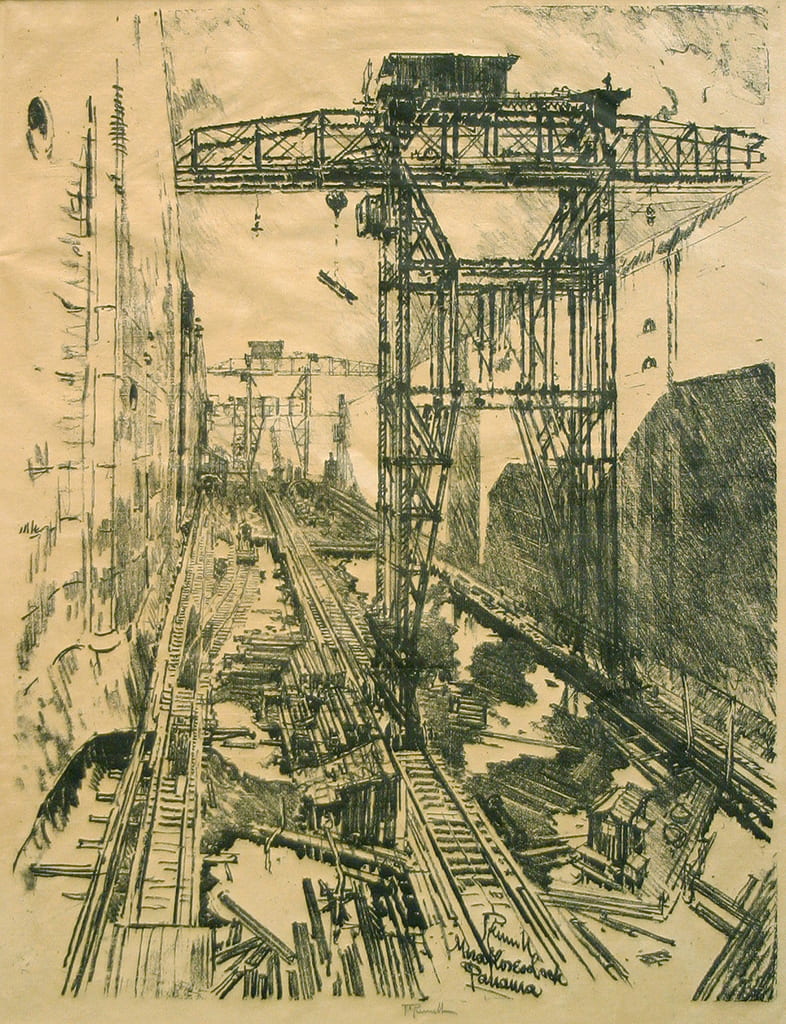

Pennell’s series of lithographs of the canal was printed in Philadelphia from drawings the artist completed on site using lithographic pencils and chalks. Their energetic lines retain the spontaneous quality of a quickly drawn sketch and capture the impressive forces, both man and machine, put to work building locks, exploding rock, and hauling earth.

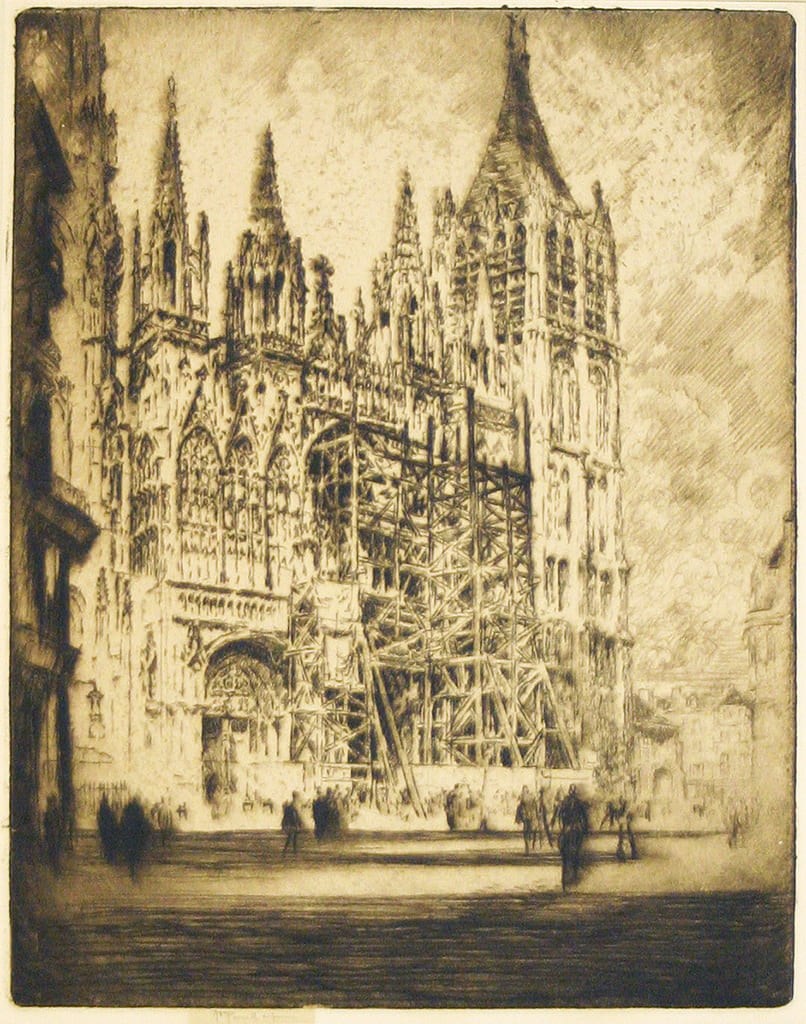

Pennell’s industrial subject matter evokes a quasi-religious sense of the sublime. In End of the Day—Gatun Lock, a crane lifts workmen from the pit at Gatun Locks, mirroring biblical scenes of the Transfiguration of Christ. The immense walls of the Pedro Miguel Locks, spanned by arches and supports, recall the great churches of Europe in earlier etchings by the artist. Pennell called their result “as fine as the flying buttresses of a cathedral.”[69] The cranes at Miraflores Locks at the Pacific end of the canal evoke towering deities. The artist visualizes industry as a kind of new god. During the Gilded Age, a gospel of industry began to identify and even compete with religion, which had been undermined by recent discoveries of science, especially Darwinian biology. The historian Henry Adams used the metaphor of the Dynamo and the Virgin to describe how modern forces of industry were supplanting those of traditional spirituality. Encountering the giant Langley engine at the Paris Exposition of 1900, he felt the dynamo as a “moral force, much as the early Christians felt the Cross…Before the end, one began to pray to it.”[70]

Pennell called his lithographs “a record of the greatest American achievement of all time,” although the labor force of the canal was largely Afro-Caribbean, recruited from such places as Barbados, Martinique, Guadalupe, and Trinidad.[71] Pennell almost entirely excluded these workers from the lithographs. His lack of focus on the workmen obscures the project’s human toll of overwork, disease, and death, and renounces any reform agenda in an era roiled by labor unrest.[72] The telling absence of workmen also expresses Pennell’s unease with the people of color he encountered in Panama and with the broader racial and cultural diversity of the increasingly interconnected world.[73]

Image credits:

Joseph Pennell (American, 1860–1926), End of the Day—Gatun Lock, The Cut—Looking Toward Culebra, Laying the Floor of Pedro Miguel Lock, and Cranes—Miraflores Lock, from the portfolio Pictures of the Panama Canal, 1912. Lithographs, 21 3/4 x 17 in., 22 1/4 x 17 in., 25 1/2 x 20 1/2 in., and 25 1/2 x 20 3/4 in. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gifts of J. Lionberger Davis, 1867.

Joseph Pennell (American, 1860–1926), West Door, St. Paul’s, 1903, and West Front, Rouen Cathedral, 1907. Etchings, 12 1/8 x 9 1/2 in. and 13 3/4 x 10 in. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. University purchases, 1908.