Resembling two leather-bound books, this boxed set of stereocards by Underwood & Underwood, one of the leading photography firms in Gilded Age America, contains one hundred views of the landscape, monuments, and people of Palestine. The Holy Land was one of the most common subjects for series of stereographs in the Gilded Age. Although they carried a hefty price tag, Holy Land stereograph collections reached hundreds of thousands of Americans, primarily in middle-class homes and schools.[48] An inscription on the inside lid of the box notes that this set was gifted to a young girl from Iowa named Edna Redeen “for perfect attendance at Sunday school.”

The popularity of stereoscopic photography of the Holy Land owed to its power to imaginatively transport the viewer. The stereoscope was an optical device that resolved two photographs of the same subject, taken at slightly different angles and juxtaposed on a card, into one image seen in depth. It simulated the bodily experience of three-dimensional space. When viewed in sequence, stereographs could further replicate the continuity of a tour or expedition. The Boston writer Oliver Wendell Holmes described viewing stereographs of the Holy Land as a virtual voyage from the comfort of his drawing room: “I pass, in a moment, from the banks of the Charles to the ford of the Jordan, and leave my outward frame in the arm-chair at my table, while in spirit I am looking down upon Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives.”[49]

Published in the accompanying guidebook Traveling in the Holy Land through the Stereoscope (1900) by the biblical scholar Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, a detailed map of Palestine delineates the sacred terrain traversed by the cards. Numbered points on the map refer to stereocards correspondingly numbered. The red line with arrows traces the route of the views, from the ancient port city of Jaffa to Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron, the Jordan River, and other areas, ending in Damascus. Branching v-shaped lines mark the “standpoints,” or places from which select views were taken, and define the boundaries of each stereograph’s field of vision. These notations promise the home viewer a tangible encounter with the Holy Land through the stereoscope, just as the land appears “to the eyes of one looking from the place where the camera stood.”[50] The topographical aspect of the map, which charts the landscape’s elevations and depths as well as distances, further alludes to the three-dimensional viewing experience made possible by stereo photography.

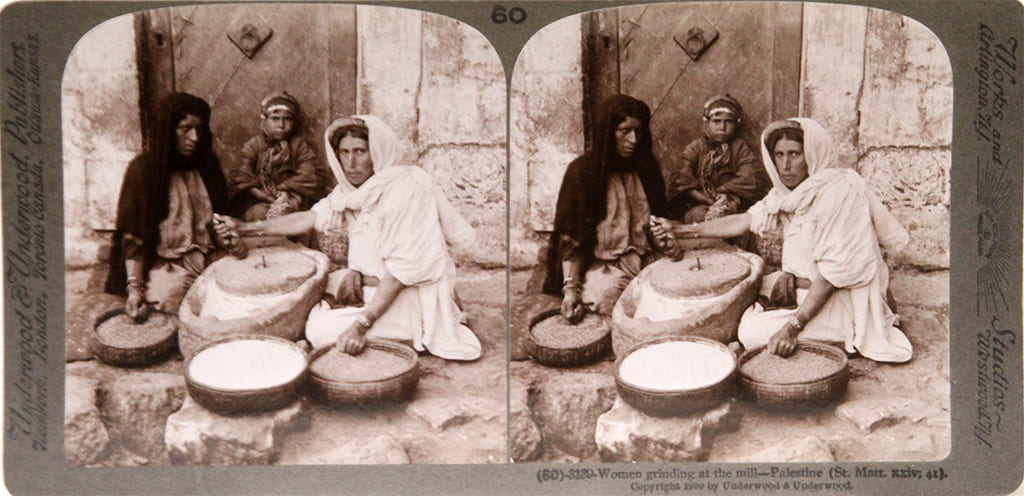

Hurlbut championed stereo photography’s ability to convincingly recreate Palestine as a tool “to make the Bible real to us,” as if a form of revelation.[51] Accordingly the images and text of the set, printed in the guidebook and as legends on the cards, focused on relating the landscape of Palestine to biblical events and drawing ethnographic comparisons between the people of the Holy Land and those of scripture. Photographs such as Women Grinding at the Mill—Palestine, captioned “How completely the life of to-day in these Oriental lands copies that of two thousand years ago!,” stressed the difference between “advanced” American viewers and the local population unaffected by change.[52] While the Palestine series could produce a greater understanding of biblical geography, its preoccupation with the scriptural past prevented Americans from appreciating the complex modernity of Middle Eastern cultures.

Image credits:

Jesse Lyman Hurlbut (American, 1843–1930), title page and map of Palestine, from Traveling in the Holy Land through the Stereoscope, c. 1900. Published by Underwood & Underwood, New York. Images courtesy of Hathi Trust.

Underwood & Underwood (American photography studio, 1882–c. 1940), Women Grinding at the Mill—Palestine, from Palestine, published c. 1906. Stereocard, 3 5/8 x 7 in. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gift of Laurie Wilson, Robert Frerck, and family, 2015.