Category: Research

Listen to an Interview with Bruce: June 16 on St. Louis on the Air (Links to an external site)

Incredible! Unique Fish Communicate With Electricity, With Human-Like Cues (Links to an external site)

These Fish Speak With Electricity, But They Talk Just Like Us (Links to an external site)

Electric Fish Also Pause to Make a Point (Links to an external site)

Can Electric Fish Talk Like Obama? (Links to an external site)

Yes, they can.

On electric fish and dramatic pauses (Links to an external site)

Scientists reveal why pausing between words creates more impactful communication

Electric fish ignore their own zaps with a cool trick (Links to an external site)

African fish called mormyrids communicate using pulses of electricity. To distinguish their own signal from those of neighboring fish, their brains inhibit sensory responses using a corollary discharge, which is an internal copy of their own motor command.

How Electric Fish Use Zeroed-out Zaps To Chat (Links to an external site)

Carlson and Matasaburo Fukutomi, a postdoctoral fellow in his laboratory, published their new research on African mormyrid weakly electric fish in the Journal of Neuroscience.

A brief, well-defined period of inhibition keeps electric fish from missing out on other important external signals, Carlson said.

Zeroing out their own zap: Time-shifted inhibition helps electric fish ignore their own signals (Links to an external site)

Electric fish generate electric pulses to communicate with other fish and sense their surroundings. Some species broadcast shorter electric pulses, while others send out long ones. But all that zip-zapping in the water can get confusing. The fish need to filter out their own pulses so they can identify external messages and only respond to those signals.

Zeroing out their own zap (Links to an external site)

“In fish that communicate with longer pulses, sensory responses to their own pulse are delayed,” said Bruce Carlson, professor of biology in Arts & Sciences. “Thus, a delayed corollary discharge optimally blocks electrosensory responses to the fish’s own signal.”

Zeroing out their own zap (Links to an external site)

Electric fish generate electric pulses to communicate with other fish and sense their surroundings. Some species broadcast shorter electric pulses, while others send out long ones. But all that zip-zapping in the water can get confusing. The fish need to filter out their own pulses so they can identify external messages and only respond to those signals.

Time-shifted inhibition helps electric fish ignore their own signals (Links to an external site)

African fish called mormyrids communicate using pulses of electricity. New research shows that a time-shifted signal in the brain helps the fish to ignore their own pulse. This skill has co-evolved with large and rapid changes in these signals across species.

Time-shifted inhibition helps electric fish ignore their own signals (Links to an external site)

Electric fish generate electric pulses to communicate with other fish and sense their surroundings. Some species broadcast shorter electric pulses, while others send out long ones. But all that zip-zapping in the water can get confusing. The fish need to filter out their own pulses so they can identify external messages and only respond to those signals.

Zeroing out their own zap (Links to an external site)

African fish called mormyrids communicate using pulses of electricity. New research from biologists at Washington University in St. Louis shows that a time-shifted signal in the brain helps the fish to ignore their own pulse. This skill has co-evolved with large and rapid changes in these signals across species.

Zeroing out their own zap: Time-shifted inhibition helps electric fish ignore their own signals (Links to an external site)

“In fish that communicate with longer pulses, sensory responses to their own pulse are delayed,” said Bruce Carlson, professor of biology in Arts & Sciences. “Thus, a delayed corollary discharge optimally blocks electrosensory responses to the fish’s own signal.”

A History of Corollary Discharge: Contributions of Mormyrid Weakly Electric Fish (Links to an external site)

Here, we review a history of neurophysiological studies on corollary discharge and highlight significant contributions from studies using African mormyrid weakly electric fish. Mormyrid fish generate brief electric pulses to communicate with other fish and to sense their surroundings.

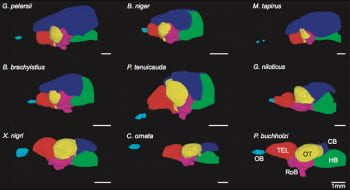

Maps show electric fish have super-sized cerebellums (Links to an external site)

Why do electric fish have such unusually large brains? (Links to an external site)

After mapping the brain of African mormyrid fish with great precision, a team of researchers has found that these fish have a larger cerebellum compared to their relatives. The experts believe this enlarged cerebellum may be linked to electric discharges that are used by the fish to communicate and locate prey. Bruce Carlson is professor of Biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He explained that the size finding in itself is not particularly surprising for those who follow this fish. This is because African mormyrid fishes are known for having a brain-to-body size ratio that is similar to humans.

New maps hint at how electric fish got their big brains (Links to an external site)

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis have mapped the regions of the brain in mormyrid fish in extremely high detail. In a new study published in the Nov. 15 issue of Current Biology, they report that the part of the brain called the cerebellum is bigger in members of this fish family compared to related fish — and this may be associated with their use of weak electric discharges to locate prey and to communicate with one another.