Panicum sp.

Panicum sp. – Panic grass

Poaceae (Graminae)

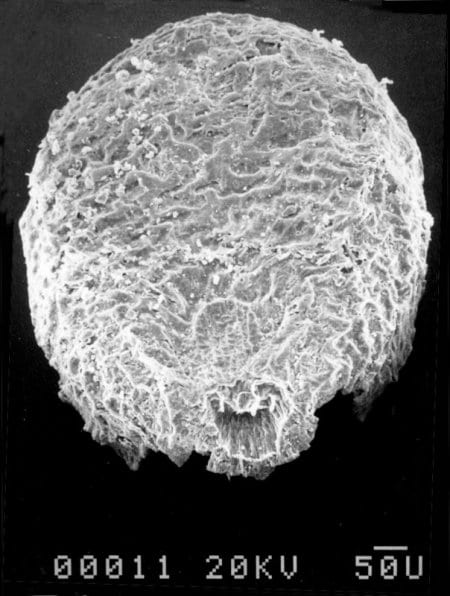

Figure 1. The dorsal side of he seed showing the position of the embryo (100x).

Panicum sp. seeds are small, elliptic grass seeds often found in fine fractions from floated archaeobotanical samples. These starchy seeds were temporarily classified as Gramineae or Poaceae Type 6L by archaeobotanists in the American Bottom area and west-central Illinois. Later, archaeobotanists identified the seeds as a panicoid-type grass, possibly belonging to the genus Panicum.

Description

Caryopsis (grains) of Gramineae Type 6L (Panicum sp.) are elliptic in shape with a slightly pointed basal end and apex. Dimensions are approximately 1 mm (length) x 0.5 mm (width) x 0.3 mm (thickness). Although sometimes mislabeled as ventral, the dorsal side of the caryopsis is slightly convex and bears an embryo (Figure 1). The embryo may be preserved on some archaeological specimens, but is often lacking, leaving a distinctive radicle depression which is also called a scutellum groove. The radicle depression extends only about one third of the length of the caryopsis, and is observable on the caryopsis forming a kind of a broad upside down “V” shape on the dorsal side. Hence, the sides of the radicle depression diverge in the Gramineae Type 6L, and are not parallel like those of Type 6F (see entry for Echinochloa muricata). The ventral side is flattish. A small, rounded hilum (the point of attachment of the grass grain to the palea) is observable as a circular depression on the basal end of the ventral side of carbonized specimens. Slight transverse wrinkles can be observed on the ventral side of the carbonized seed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ventral side of the same seed showing the hilum and slight transverse wrinkles (100x).

Archaeological Distribution

Panicumsp. seeds were identified in paleofecal specimens from Salts Cave, dating to the Early Woodland Period (Yarnell 1969). However, at that time no specific type (e.g., Gramineae Type 6L) was assigned to these panic seeds, and hence seeds from paleofecal specimens could possibly belong to some other type of Panicumspecies. A few seeds of panic grass have been identified from the Smiling Dan site in Illinois, dating to the Middle Woodland period (Asch and Asch 1985). Lopinot (1982) identified many naked whole Panicum sp. seeds and fragments from the Bridges Site, also in Illinois. More than 3,000 specimens from Feature 339 at this site were identified. In addition, Panicum sp. seeds were identified by many archaeobotanists from the Mississippian components of the sites excavated during the FAI-270 Project in the American Bottom area, Illinois. In the Stirling phase component of the Turner site (Whalley 1983), panic grass seeds represent nine percent of the identifiable seeds. Furthermore, Lopinot (1991) has identified Panicum sp. grass seeds from pits and features from all the phases at the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II site. The ubiquity index is 69.45% (percent of features in which panic grass seeds are present) for the Moorehead phase of the Mississippian Period. The taxon occurs most frequently at the Sand Prairie component of the Julien site (Johannessen 1984). Furthermore, Wagner (1987) has identified panic grass seeds from the Incinerator site in Ohio and other Fort Ancient sites.

Modern Plant and its Distribution

There are over 170 annual and perennial species of Panicum growing in various habitats in North America. The center of abundance of North American species is in the Southeast. The plants are mainly inhabitants of fields and waste places, but some appear in moist low areas, while others appear on dry rocky uplands and open woods (Hitchcock 1950).

Discussion

Because there are so many native Panicum species, archaeobotanists are not yet able to identify Gramineae Type 6L to the exact species of Panicum genus. However, Type 6L does not belong to the Panicum species that have very elongated seeds, nor to those with rather circular grains. In many archaeobotanical assemblages from eastern North American sites, Gramineae Types 6L, 6F and 20/21 occur together, and Johannessen (1983) has illustrated all three types.

Several suggestions about the use of panic grass have been proposed. If panic seeds are associated with high numbers of stem and leaf fragments, Asch and Asch (1985) suggested that finds of Panicum sp. might be interpreted as evidence of technological use of plants for thatching, matting, lining of pits, etc. However, at Smiling Dan such association is lacking, and the authors explicitly state that there is no evidence for a nonfood use of Panicum sp. at this site (Asch and Asch 1985:390). According to the authors, Panicum sp. grains are minute, so the occasional harvesting from a dispersed plant population would not be practical. Similarly, Yarnell (1969:44) implied that the panic seeds present in paleofeces from Salts Cave may not have been intentionally collected. In contrast, Lopinot (1983) argues that association of non-woody stem fragments with panic seeds is random, interpreting a high concentration of Panicum sp. seeds in cache or storage pits as evidence of prehistoric food use. He therefore classifies panic seed in his category of “economic native seeds”. According to Wagner’s (1987) interpretation, small-seeded plants, including panic grass, could have been deliberately grown, or left unattended in fields, or carried back to the village for human consumption at the Incinerator site in Ohio. Although there is good ethnohistoric evidence for the use of panic seeds from the American Southwest and many other parts of the world, I could find no precise evidence for the use of panic seeds by Native groups from eastern America.

Written by: Ksenija Borojevic

References

- Asch, D. L., and N. B. Ash

1985 Archaeobotany. In Smiling Dan: Structure and Function at a Middle Woodland Settlement in the Lower Illinois Valley, edited by B. D. Stafford and M. B. Sant, pp. 327-401. Center for American Archaeology Research Series Vol. 2. Kampsville, Illinois. - Hitchcock, A. S.

1950 Manual of Grasses of the United States. United States Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publications 200. - Johannessen, S.

1984 Plant Remains from the Julien Site. In The Julien Site, edited by G. R. Milner, pp. 244-276. American Bottom Archaeology FAI-270 Site Reports, Vol. 7. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

1983 Plant Remains. In The Robinson’s Lake Site, edited by G. R. Milner, pp. 124-132. American Bottom Archaeology FAI-270 Site Reports, Vol. 10. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. - Lopinot, N. H.

1991 Archaeobotanical Remains. In The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Biological Remains. Preservation Agency, Springfield.

1982 Archaeobotany of the Bridges Site. In The Bridges Site (11-Mr-11): A Late Prehistoric Settlement in the Central Kaskaskia Valley, by M. L. Hargrave, G. A. Oetelaar, N. H. Lopinot, B. M. Butler, and D. A. Billings, pp. 248-276. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Research Paper No. 38. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. - Wagner, G. E.

1987 Uses of Plants by the Fort Ancient Indians. Unpublished Ph. D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis. - Whalley, L.

1983 Plant Remains from the Turner Site. In The Turner (11-S-50) and DeMange Sites (11-S-447), edited by G. R. Milner, pp. 213-233. American Bottom Archaeology FAI-270 Site Reports, Vol. 4. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. - Yarnell, R. A.

1969 Contents of Human Paleofeces. In The Prehistory of Salts Cave, Kentucky, edited by P. J. Watson, pp. 41-54. Illinois State Museum, Reports of Investigation 16. Springfield.