Introduction

Economic choice is the behavior observed when individuals make choices solely based on subjective preferences – for example when choosing between dishes on a restaurant menu, between possible financial investments, or between different career paths. (1) Economic choice is an intrinsically fascinating topic, intimately related to philosophical questions such as free will and moral behavior. (2) Generations of economists and psychologists accumulated a rich body of knowledge, identifying concepts and quantitative relationships that describe economic choices. Thus choice is a rare case of high cognitive function for which we have a formal and quantitative behavioral description. This background can be used to guide and constrain research in neuroscience. (3) Economic choice is relevant to a constellation of mental and neurological disorders, including frontotemporal dementia, schizophrenia, major depression and drug addiction.

Options available for choice in different situations can vary on many dimensions. For example, different flavors of ice cream evoke different sensory sensations and may be consumed immediately; different houses for sale may vary for their price, their size, the school district, and the distance from work; different financial investment may carry different degrees of risk, with returns available in a distant, or not-so-distant, future. How does the brain generate choices in the face of this enormous variability? Economic and psychological theories of choice behavior have a cornerstone in the concept of value. While choosing, individuals assign values to the available options; a decision is then made by comparing values. Hence, while options can vary on multiple dimensions, value represents a common unit of measure to make comparisons. From this perspective, understanding the neural mechanisms of economic choice amounts to describing how values are computed and compared in the brain.

Recent discoveries

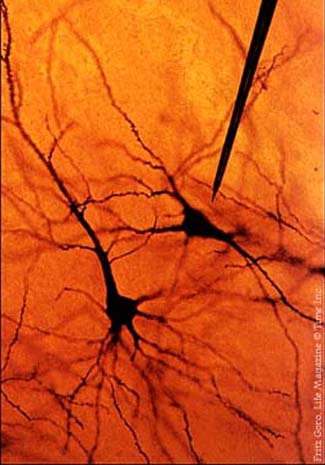

Representation of goods and values in orbitofrontal cortex. Much of our research has been devoted to understanding how subjective values are represented at the neuronal level. In our experiments, monkeys choose between different juices offered in variable amounts. The (subjective) relative value of the juices is inferred from choices and used to interpret neuronal activity (Padoa-Schioppa 2011). Many studies have focused on the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), where we found three groups of cells encoding the value of individual offers (offer value), the value of the chosen good (chosen value) and the binary choice outcome (chosen juice) (Padoa-Schioppa and Assad 2006). Our finding have been replicated in a large number of studies, and value signals were also found in other brain regions. Until recently, however, it was unclear whether values encoded in OFC – or anywhere in the brain – are causally related to choices. This question is critical because values can guide a variety of mental functions such as associative learning, perceptual attention, and emotion. In a recent study, we used electrical stimulation to demonstrate that offer values encoded in OFC are causal to choices (Ballesta et al 2020). This important result validates a large body of work conducted by us and many other labs.

Context adaptation. A central focus has been to understand how the neuronal representation in OFC depends – or does not depend – on the behavioral context of choice. We discovered several phenomena. (1) One study found that the activity of neurons encoding the value of a particular good does not depend on what other goods are offered in alternative. This trait, called “menu invariance”, is very consequential because it implies choice transitivity (Padoa-Schioppa and Assad, 2008). (2) The number of different goods available for choice is very large, potentially infinite. How does the brain cope with this variability? In one study, we divided sessions in two blocks of trials, and we offered different juices in the two blocks. We found that OFC neurons associated with one particular juice in the first block remapped and became associated with a different juice in the second block. At the same time, the functional role of different neurons remained stable across trial blocks. In other words, offer value cells remained offer value cells, etc. Thus the same neural circuit could subserve decisions in many different contexts. (3) Values available in different contexts can vary substantially – the same person might choose between goods worth a few dollars or between goods worth thousands of dollars. We discovered that the encoding of value in OFC adapts to the range of values available in any given condition – a phenomenon termed range adaptation (Padoa-Schioppa 2009; Conen and Padoa-Schioppa 2019). We also showed that range adaptation in the encoding of offer values is optimal as it ensures maximal expected payoff (Rustichini et al 2017).

Decision mechanisms. There is now broad consensus that values are explicitly represented at the neuronal level. In contrast, where in the brain and how exactly values are compared to make a decision remains an open question. Some scholars proposed that values are compared (i.e., decisions are made) in motor systems; others proposed that decisions take place across a large number of areas. Notably, the groups of cells identified in OFC capture both the input (offer value) and the output (chosen juice, chosen value) of the decision process. This consideration lead us to propose that these neurons constitute the building blocks of a decision circuit. Several lines of evidence support this view. (1) Theoretical work shows that the cell groups in OFC are computationally sufficient for binary choices. In other words, one can build a biophysically realistic neural network that generates decisions and whose elements resemble the cell groups identified in OFC (Rustichini and Padoa-Schioppa 2015). (2) Several studies examined near-indifference offers, for which animals split choices. They found that choice variability correlates with variability in the firing rate of each cell group (Padoa-Schioppa 2013; Conen and Padoa-Schioppa 2015). (3) Disrupting neuronal activity in OFC disrupts decisions (i.e., it increases choice variability; see below).

Economic choices in mice. In summary, it seems likely that economic decisions take place in a neural circuit within the OFC. However, this neural circuit is poorly understood. For example, it is unclear whether different groups of neurons identified in this area correspond to different anatomical cell types, whether they reside in different cortical layers, how exactly they are connected with each other, and whether they are differentially connected with other brain regions. These questions are hard to tackle with traditional neurophysiology, but they can be addressed in principle using genetic tools. Hence, in collaboration with Tim Holy, we recently developed a mouse model of economic choice behavior. We found that optogenetic inactivation of the lateral orbital (LO) area severely disrupted choices. Furthermore, neuronal recordings in LO identified different groups of cells analogous to those previously found in the primate OFC. The main difference is that in the monkey OFC, options and values are represented in the reference frame defined by the juice types (good-based representation). In contrast, in the mouse LO, the representation of options and values in spatial (Kuwabara et al 2020)

Current directions

Ongoing research proceeds in several directions:

- Generalizing current notions. Current notions rely almost exclusively on studies in which two options were offered simultaneously. However. in many real-life situations, options appear or are considered in sequence. Similarly, choices often entail three or more options. We want to assess whether notions emerged from previous studies generalize to more complex situations. Furthermore, we want to use more complex choice tasks to address open questions about the decision mechanisms and context adaptation.

- Role of other brain regions. In addition to OFC, we previously examined neuronal activity in lateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala (Jezzini and Padoa-Schioppa 2020). We are currently examining neuronal activity in gustatory cortex, and we plan to extend our investigation to visual cortex and other brain regions.

- Dissecting the decision circuit. We are using our mouse model to dissect the (putative) decision circuit. In particular, we are working to assess whether different groups of cells identified in relation to choice behavior have specific anatomical identity, layer location and long-range connectivity.