Chemical composition of meteorites

I suggest to persons who think that they have found a meteorite to get a chemical analysis from a lab that can provide what we geochemists call “whole-rock” elemental composition data. There are several different ways to determine whether or not a rock is a meteorite. A chemical analysis is a good one because it is cheaper to do than most other tests and the results are usually unambiguous. That means, with a chemical analysis, I am not likely to say, “I still don’t know” or “maybe.”

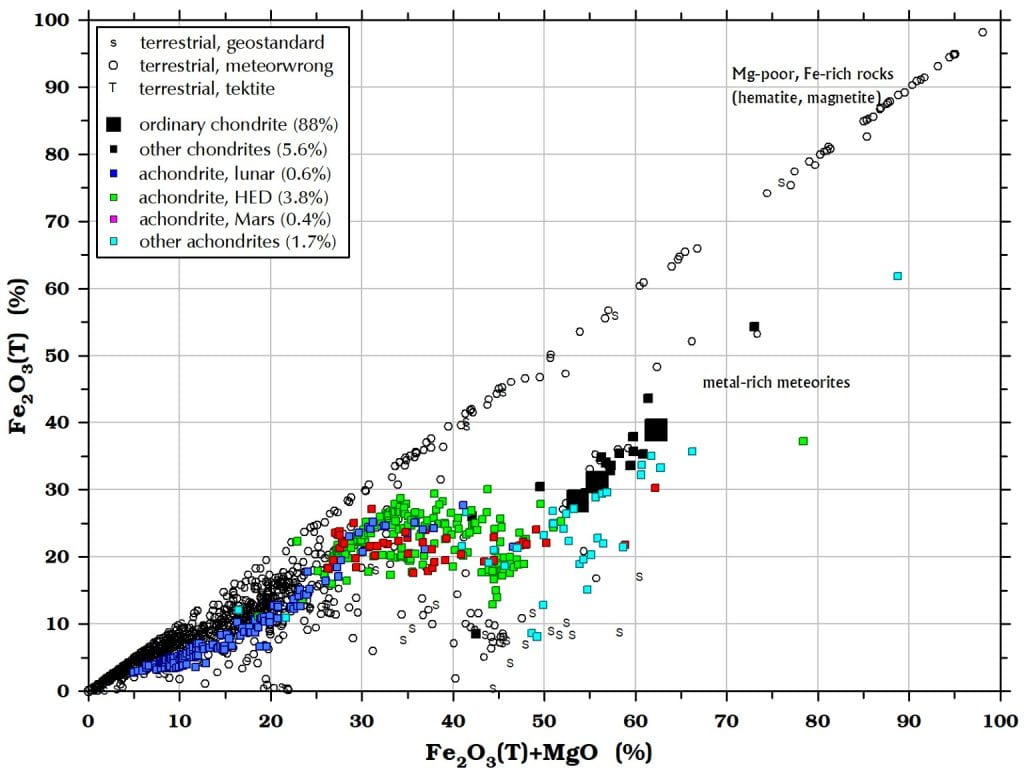

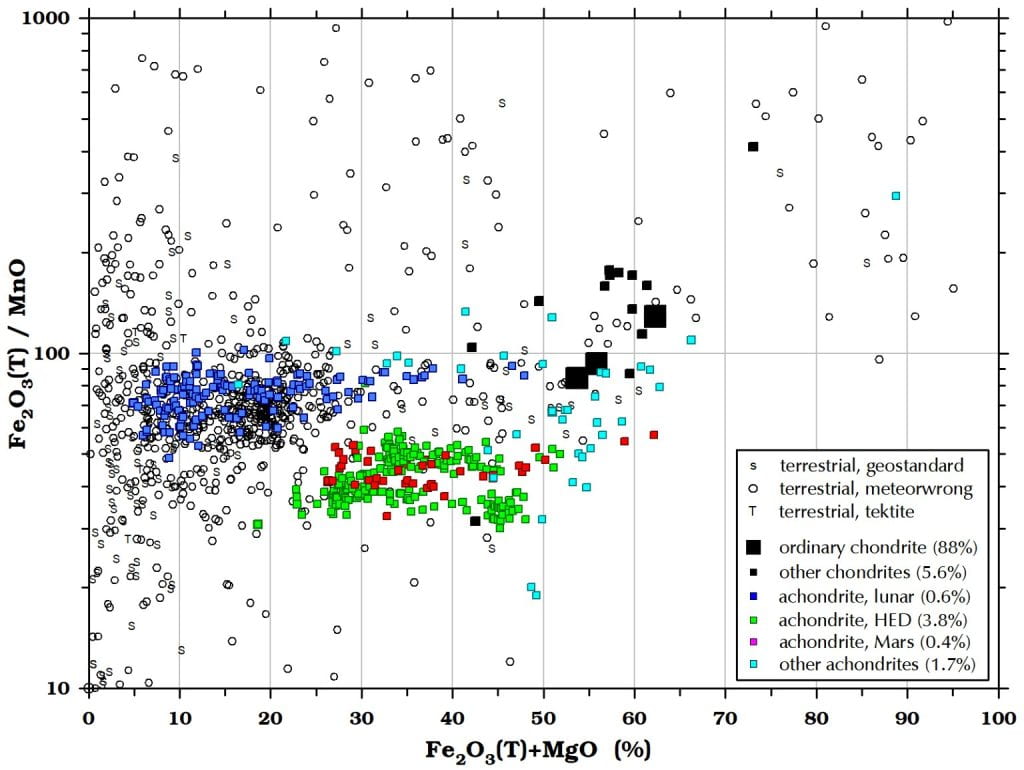

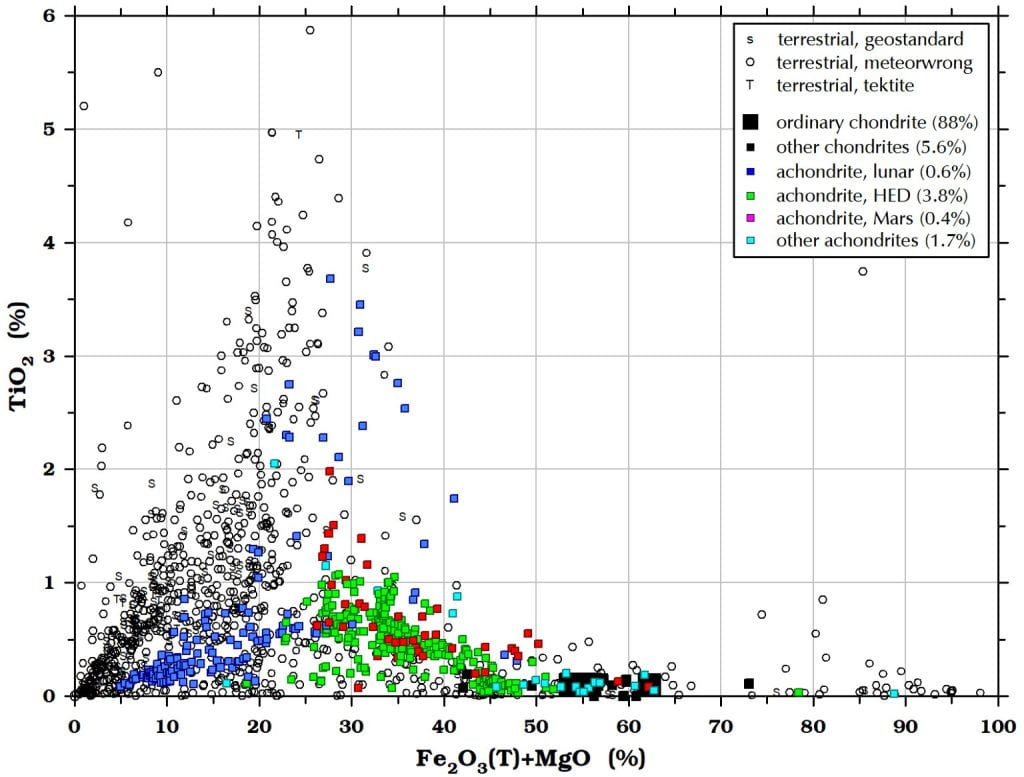

So that you can check your data yourself, I show plots here of concentrations and concentration ratios of several chemical elements in meteorites compared to rocks that persons have had analyzed by commercial labs. Except for Mn (manganese), Cr (chromium), and Ni (nickel) all of the elements plotted here are what geochemists call “major elements” because they typically occur at percent-level concentrations. Major elements reflect the mineralogy, which is the best way to distinguish most meteorites from Earth rocks.

The horizontal axis of all the plots is “Fe2O3(T)+MgO.” Most labs that are in the business of analyzing rocks report the iron concentration as “total iron (T) as Fe2O3” because in Earth rocks much or most of the iron occurs as Fe(III), that is, ferric iron. There is little or no Fe(III) in freshly fallen meteorites, however; it is all Fe(II), ferrous iron, and Fe(zero), metal. For convenience, however, I use Fe2O3 in the plots. If you had an analysis done, just add the Fe2O3 and MgO values together for comparison. If you have Fe values reported as FeO, just multiply the FeO value by 1.111 to get Fe2O3.

In the legends, the percentages (%) represent the relative abundance of each meteorite type among stony meteorites. I cannot emphasize this enough: Most (88%) stony meteorites are ordinary chondrites; all the other types are rare.

Figure 1. Many terrestrial rocks have higher concentrations of SiO2 (silica) than any meteorite because they contain quartz and meteorites do not contain any significant amount of quartz or other silica minerals. If SiO2 is greater than 60%, then the rock is not a meteorite. The only possible exception would be a lunar granite, which is a volumetrically insignificant component of the Apollo collection and no granitic meteorites have yet been found. The low-SiO2 terrestrial rocks are mainly limestones [low Fe2O3(T) + MgO] and iron ores [high Fe2O3(T) + MgO]. Nearly all of the terrestrial rocks with 12-26% Fe2O3(T)+MgO and 45-52% SiO2 are basalts. Some meteorites are basalts (lunar, Mars, HEDs) but planetary basalts tend to have greater Fe2O3(T)+MgO (22-42%) and Cr but and lower Al2O3, Na2O, and K2O than terrestrial basalts of the same Fe2O3(T)+MgO (below).

Figure 2. Most meteorites, especially lunar meteorites, have higher concentrations of aluminum (Al2O3) than terrestrial rocks of similar Fe2O3+MgO. For an explanation of why lunar meteorites plot along the diagonal trend, see How do we know that it is a rock from the moon? and The chemical compostion of lunar soil. Feldspars (or clays derived therefrom) are the major carrier of aluminum in terrestrial rocks, too. Chondrites have low concentrations of Al2O3 because they contain little feldspar.

Figure 3. Lunar meteorites also have high concentrations of calcium (CaO) because most of the plagioclase is the Ca-rich extreme of plagioclase, anorthite. Terrestrial rocks with high CaO are usually rich in calcite (calcium carbonate), like the limestones that plot around 50% CaO. The terrestrial rocks that plot with the martian meteorites are mostly basalts, which have similar mineralogy to the martian basalts (but see Na2O and K2O below). Chondrites have low concentrations of CaO. Again, 88% of stony meteorites are chondrites, so high-Ca rocks are probably not meteorites.

Figure 4a. The ratio of CaO to Al2O3 varies greatly in terrestrial rocks.

Figure 4b. In contrast, in most meteorites, virtually all the Al2O3 and most of the CaO is carried by feldspar, so there is little variation in CaO/Al2O3.

Figure 5. Among meteorites, magnesium (MgO ) necessarily increases with Fe2O3(T)+MgO. Some terrestrial rocks lie off the trend because they have MgO/Fe2O3(T) ratios outside the range for meteorites. High-MgO terrestrial rocks are mainly ultramafic rocks like peridotites, dunites, and serpentinites. Low-MgO rocks are rich in quartz, calcite, or hematite.

Figure 6. The same is largely true for iron [Fe2O3(T)]. High-Fe2O3 meteorwrongs are iron ores, often hematite concretions.

Figure 7. The ratio of magnesium to iron does not vary greatly among most kinds of stony meteorites. Rocks with MgO/Fe2O3(T) <0.2 or >6 are probably not meteorites. Only rare lunar granites have low MgO/Fe2O3(T), and none of these has been found as a meteorite.

Figure 8a. The ratio of manganese to iron varies greatly among terrestrial rocks.

Figure 8b. The ratio of manganese (MnO) to iron does not vary much within different groups of meteorites. The Fe2O3(T)/MnO ratio (or Fe/Mn or FeO/MnO) is not as reliable a test for meteorites as some sources imply, although ratios of <60 are inconsistent with lunaites and >50 are inconsistent with eucrites, for example. Many earth rocks have Fe2O3(T)/MnO in the range of meteorites.

Figure 9. Sodium (Na2O) is one of the best elements for distinguishing between terrestrial rocks and meteorites. Most terrestrial rocks are richer in Na2O than any meteorite. Rocks with >2% Na2O are probably not meteorites. The high-Na achondrite is Grave Nunataks (GRA) 06128/9.

Figure 10. Sodium (Na2O) and potassium (K2O) are both alkali elements and all meteorites have low concentrations of all alkali elements compared to most terrestrial rocks. Rocks with greater than 0.6% K2O are probably not meteorites.

Figure 11. One of the best elements for distinguishing meteorites from Earth rocks is chromium (Cr). Nearly all stony meteorites have high concentrations of Cr compared to most Earth rocks. The most Cr-poor meteorites are the feldspathic lunar meteorites, which have high concentrations of Al2O3 and CaO. Cr-rich terrestrial rocks tend to be ultramafic rocks like dunites, peridotites, pyroxenites, and serpentinites. Most of the meteorwrong analyses of this plot were done by Actlabs, and Actlabs has a detection limit for Cr of 20 ppm. I have plotted all Actlabs data reported as “<20 ppm” at 10 ppm. The two low-Cr points for martian meteorites (~100 ppm) represent the two stones of Los Angeles.

Figure 12. Concentrations of nickel (Ni )are high in chondrites, typically 10,000-16,000 ppm (1.0-1.6%). Nickel data are often not useful for identifying achondrites because many achondrites have Ni concentrations in the range of terrestrial rocks. Ten of the 780 Actlabs analyses of “meteorwrongs” plotted here are, in fact, meteorites: 8 ordinary chondrites, 1 pallasite, and 1 iron meteorite. I know that about half of these real meteorites were purchased and the buyer had them analyzed to determine if they were real meteorites. Actlabs has a detection limit for Ni of 20 ppm. I have plotted all Actlabs data reported as “<20 ppm” at 10 ppm. Similarly, Actlabs usually reports Ni concentrations for ordinary chondrites as “>10,000 ppm.” I have plotted all these data at exactly 10,000 ppm.

Figure 13. Titanium (TiO2) is not particularly useful for distinguishing meteorites from Earth rocks except for Earth rocks with <20% Fe2O3(T)+MgO . Only basaltic lunar meteorites have >2% TiO2. Some Apollo basalts have 10-12% TiO2 but no such meteorites have yet been found among the lunar meteorites.

Notes, Caveats, and References

1) Terrestrial – Meteorwrong. All the “meteorwrongs” in the plots (white circles) represent rocks that persons have had analyzed and have been sent to me the results. As I note in the Ni (nickel) plot above, 8 of the “meteorwrongs” are actually meteorites.

2) Terrestrial – Geostandard. Many countries have agencies that pulverize large quantities of rock for use as interlaboratory comparison standards. Several hundred geostandards are available that represent all common, and many uncommon, rock types of the earth. For most of these, there are many analytical data available. I have selected from the compilation of Govindaraju (1994) and Korotev (1996) data for 156 such rocks. I have avoided data for soils and unconsolidated sediments, monominerallic rocks (except chert, sandstone, limestone, hornblendite, magnesite), ores (except for some iron ores because these are sometimes mistaken for meteorites), and geostandards that do not have data for the elements that I plot here. In total there are geostandards data for 7 andesites, 5 anorthosites, 17 basalts, 2 carbonatites, 1 chert, 6 diabases, 2 diorites or diorite gneiss, 2 dolomites, 4 dunites, 15 gabbros, 21 granites and related rocks, 5 granodiorites, 1 hornblendite, 6 iron ore or iron-formation rocks, 2 kimberlites, 1 quartz latite, 10 limestones, 2 lujavrites, 1 magnesite, 1 monzonite, 1 norite, 3 peridotites, 1 pyroxenite, 5 rhyolites (including 1 obsidian), 1 sandstone, 5 schists, 3 serpentinites, 12 shales, 2 slates, 6 syenites, 2 tonalites, 3 trachytes, and 2 “ultrabasic rocks.”

3) Terrestrial – Tektite. I have plotted data of Koeberl (1986) for various types of tektites. Note that tektites have compositions like terrestrial rocks (because they are terrestrial rocks!), not like meteorites.

4) All (but 8) of the white points represent terrestrial rocks. All the black points and colored points are for meteorites.

5) All the meteorites in the plots (all square symbols) are stony meteorites, not stony-irons or irons.

6) Most stony meteorites are chondrites, and most chondrites are ordinary chondrites. If you have actually found a meteorite, it is probably some kind of chondrite. That is why I made the points for chondrites black and the ordinary chondrites BIG and black. Chondrites are most dissimilar to Earth rocks. Each black point represents the average composition of one of the chondrite groups: H, L, LL, EH, EL, CI, CM, CV, CO, CR, CO, R, Ac, & K. Data from Wasson & Kallemeyn (1988).

7) The lunar meteorite data are from my own database. Each point represents a different meteorite.

8) For the martian meteorites, eucrites, howardites, diogenites, and “other rare achondrites,” each point represents a meteorite or analysis. Data mostly from Jarosewich (1990), Lodders & Fegley (1998), and Mittlefehldt et al. (1998).

9) The plots presented here reasonably represent >99% of all meteorites.

10) It is like lottery numbers – you do not win unless the composition is consistent with ALL the chemical-composition parameters, not just some of them!

11) I have not shown data for trace elements other than Mn, Cr, and Ni. Data for individual trace elements like Rb, Sr, Zr, Hf, Nb, Ta, Th, U, and the REE (rare-earth elements) are not always useful for distinguishing earth rocks from planetary rocks, although ratios among these elements are often very useful, e.g., rare earth “patterns.”

12) I should show some plots here for chalcophile (sulfur-loving) elements – Cu, Zn, As, In, Sn, and Sb. The problem is that the concentrations of these elements are so low in achondrites that there are few data to plot. Chondrites have considerably higher concentrations of chalcophile elements than do achondrites.

Chalcophile-element concentrations in chondrites (range of group means of Wasson & Kallemeyn, 1988). Values in ppm

| Cu | Zn | As | In | Sn | Sb |

| 80–185 | 17–312 | 1–4 | 2–80 | 0.7–1.8 | 0.06–0.2 |

So, for example, if you have a rock with >5 ppm As (arsenic), then the rock is not a meteorite. Many terrestrial sedimentary rocks, as well as metamorphic rocks that formed from sedimentary rocks, have concentrations of chalcophile elements much higher than those in the table above.

References

Govindaraju K. (1994) 1994 compilation of working values and sample description for 383 geostandards. Geostandards Newsletter 18, 1–158.

Jarosewich E. (1990) Chemical analysis of meteorites: A compilation of stony and iron meteorite analyses. Meteoritics 25, 323-327.

Koeberl C. (2006) Geochemistry of tektites and impact glasses. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 1986 14, 323-350.

Korotev R. L. (1996) A self-consistent compilation of elemental concentration data for 93 geochemical reference samples. Geostandards Newsletter 20, 217–245.

Lodders K. and Fegley B. Jr. (1998) The Planetary Scientist’s Companion, Oxford University Press, New York, 371 pp.

Mittlefehldt D. W., McCoy T. J., Goodrich C. A., and Kracher A. (1998) Chapter 4. Non-chondritic meteorites from asteroidal bodies. In Reviews in Mineralogy, Vol. 36, Planetary Materials (ed. J. J. Papike), pp. 4-1–4-195, Mineralogical Society of America, Washington.

Wasson J. T. and Kallemeyn G. W. (1988) Compositions of chondrites. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A 325, 535-544.