Active Projects

Universal Organic Recycler

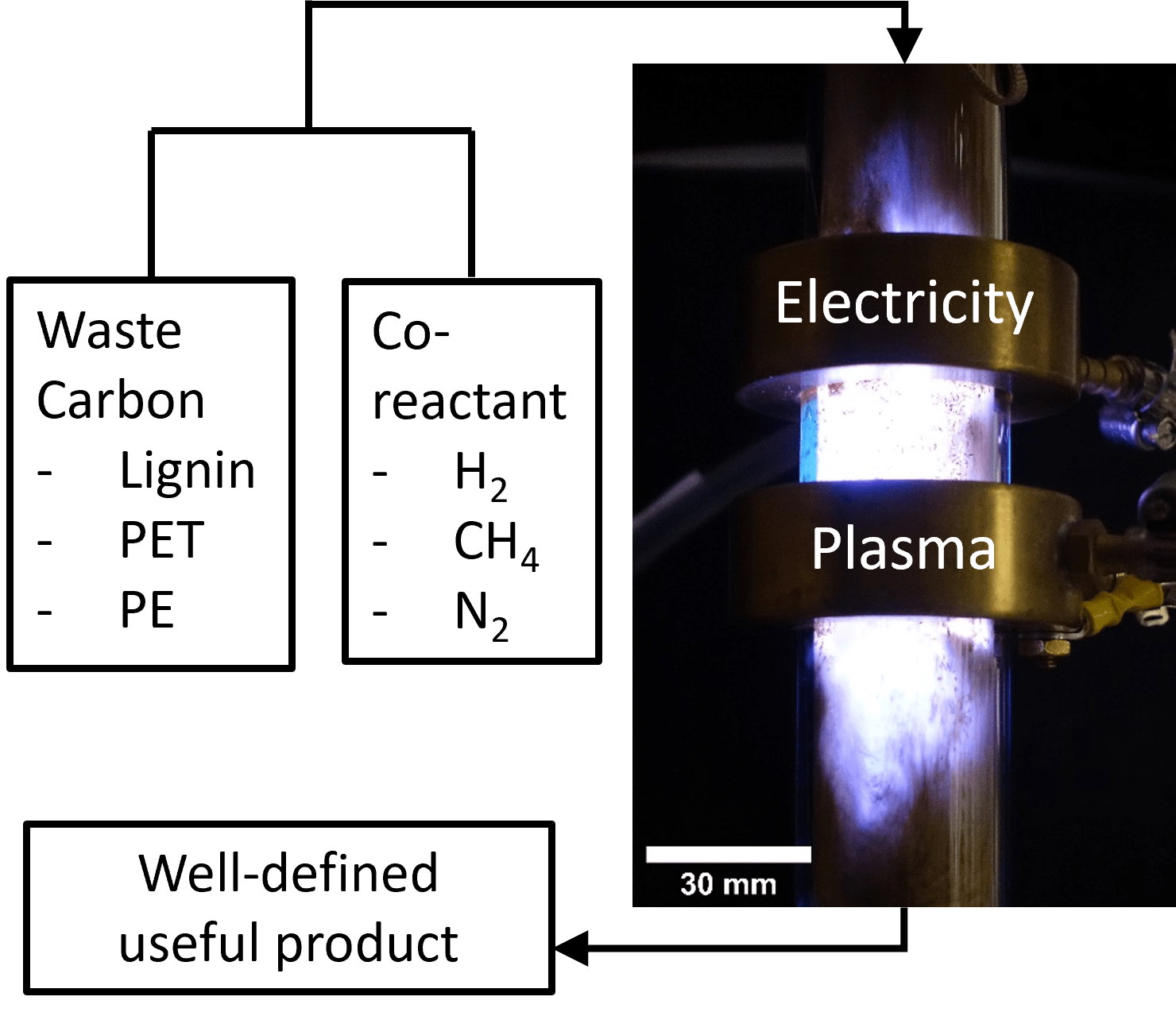

Many of the products we rely upon are carbonaceous, and for good reason. They may be very lightweight with excellent mechanical properties, such as fiber reinforced plastics, or they may be highly corrosion resistant compared to metals. To realize a sustainable future, we want to minimize the carbon used from fossil resources. That will require increased utilization of waste components of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g. lignin), and also reuse of the carbon in plastic waste such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyethylene (PE). If cost-effective ways of recycling the carbon in waste plastic can be developed, then there is an economic incentive to avoid accumulation in the environment.

Our vision is to develop a Universal Organic Recycler driven by renewable electricity that can accept a wide range of waste carbonaceous materials such as lignin, PET and PE to produce a narrow well-defined product distribution from which fresh materials can be synthesized. There is a connection to gasification, but we are interested in intermediates other than synthesis gas (CO + xH2). For this work, we are interested in collaborating with experts in catalysis and renewable resources / waste management.

Figure 1. An early conception of an organic processor from the IRG.

Plasma-Liquid Selective Organic Chemistry

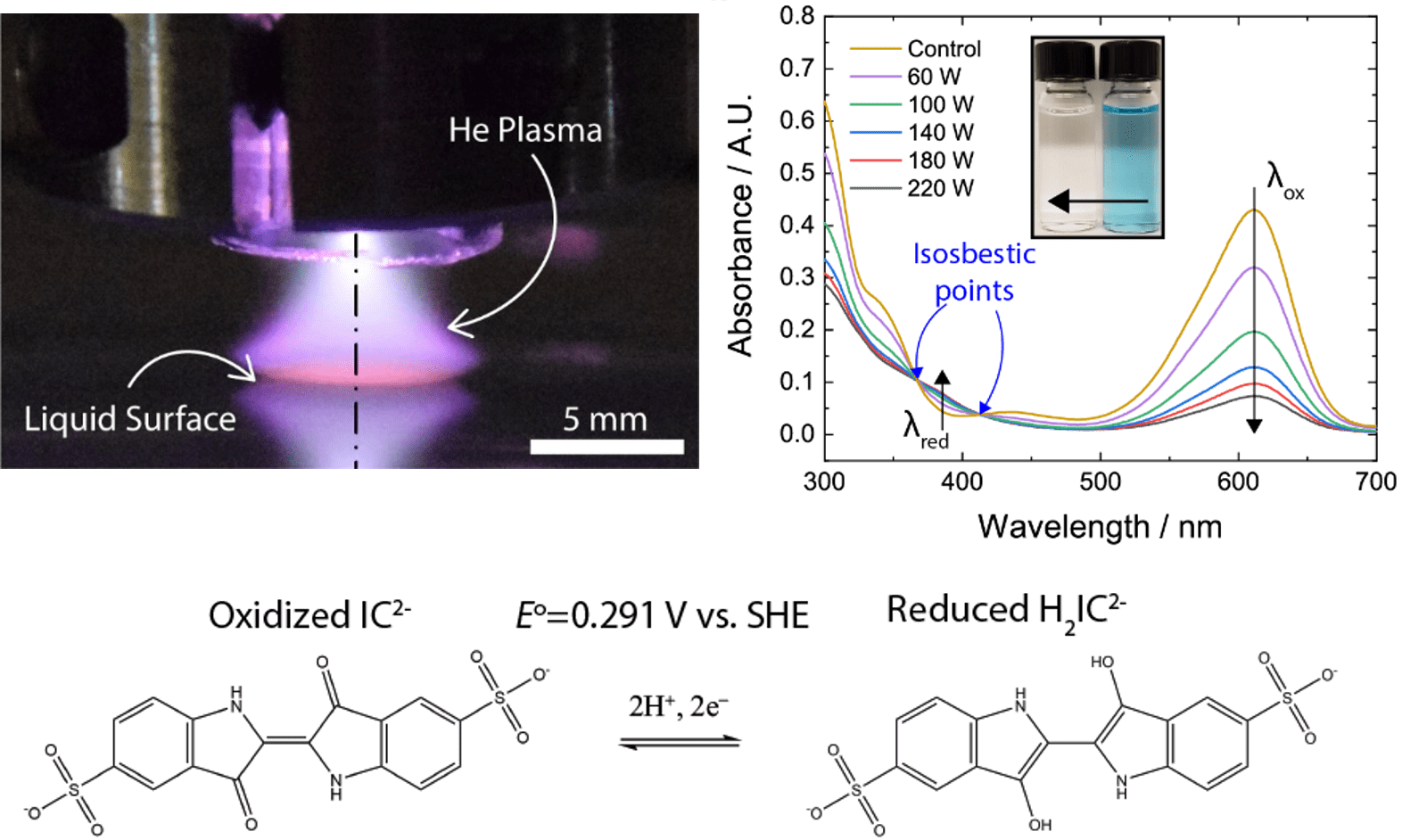

Many organic chemistry reactions, for example of interest to the pharmaceutical industry, involve hazardous reagents. Some specific examples are the Birch reaction, which requires metallic sodium metal dissolved in liquid ammonia, or fluorination chemistry, which requires hydrogen fluoride or fluorine gas, both of which are extremely dangerous. In some cases, such as fluorination chemistry, the hazardous and unpredictable reactivity of the reagents slows the progress of research through practical limitations related to safety.

We are interested in using Plasmas in Contact with Liquids to promote, using benign reagents, organic reactions in solution that would otherwise require hazardous precursors. The focus here is on high value products, for example of interest to the pharmaceutical industry. For this work we are interested in collaborating with organic chemists and specialists in plasma diagnostics.

Figure 2. Low temperature plasma in contact with water selectively reduces indigo carmine without side reactions, as evidenced for example by the observation of isosbestic points in the UV-VIS absorbance spectrum.

Nanomaterial Synthesis and Characterization

The properties of materials change when their characteristic size is shrunk down to the nanometer length scale. At the same time, the very large specific interfacial area presented by these materials makes them unstable. We are interested in exploring nanomaterials that are chemically and physically stable in demanding environments. For applications, we are interested in several areas, for example:

- Deep ultraviolet solid state light sources

- Tunable across the visible materials for photocatalysis and photoelectrochemistry

- Quantum sensing

- Super hard structural ceramics

For composition, we are interested in III-nitride materials based upon gallium nitride, for example GaN, InGaN, and GaSbN for applications involving light and electron transport. For structural ceramic applications, we are interested in Al2O3, particularly nanocrystalline alpha-Al2O3, and cubic BN. For nanomaterials we are interested in collaborating with application experts. We specialize in synthesis and characterization.

Figure 3: Nanomaterials. (left) Single freestanding GaN quantum dot. (middle) Photoluminescence (PL) from GaN quantum dots under different excitation energies in the range from 4.5 to 5.0 eV. (right) Hardness of nanostructured alumina ceramics as a function of particle diameter showing a maximum at approximately 10 nm.

Thermodynamics

One of the greatest scientific challenges of the 21st century is using thermodynamics to describe processes that operate far, especially very far, away from local equilibrium. Our hypothesis is that even in systems that operate very far away from local equilibrium, such as low temperature plasmas, chemical reactions are still end-state driven, and in that sense, are similar to reactions governed by local equilibrium. However, the end-state of chemical reactions in systems that operate very far from local equilibrium can be different from those that are governed by local equilibrium. Along these lines, we are interested in questions such as:

- How can chemical speciation at nonequilibrium end-states be predicted from the process state variables?

- Are those predictions consistent with experimental observations?

- Does the entropy generation rate reach an extremum? Under what circumstances is that extremum a minimum or a maximum?

Figure 4: Nonequilibrium thermodynamics. (left) Systems governed by local equilibrium (blue) and superlocal equilibrium (red) proceed to fundamentally different stationary states. (middle) Example of a system governed by local equilibrium. (right) Example of a system governed by superlocal equilibrium.