by Kelly L. Schmidt and Cecilia Wright. Last updated July 2022.

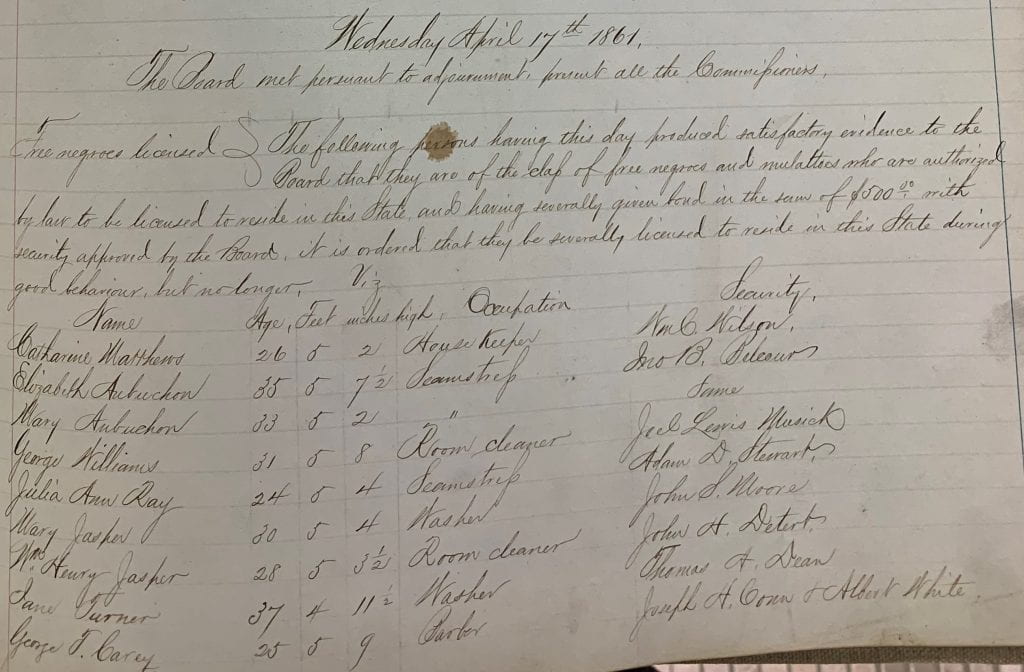

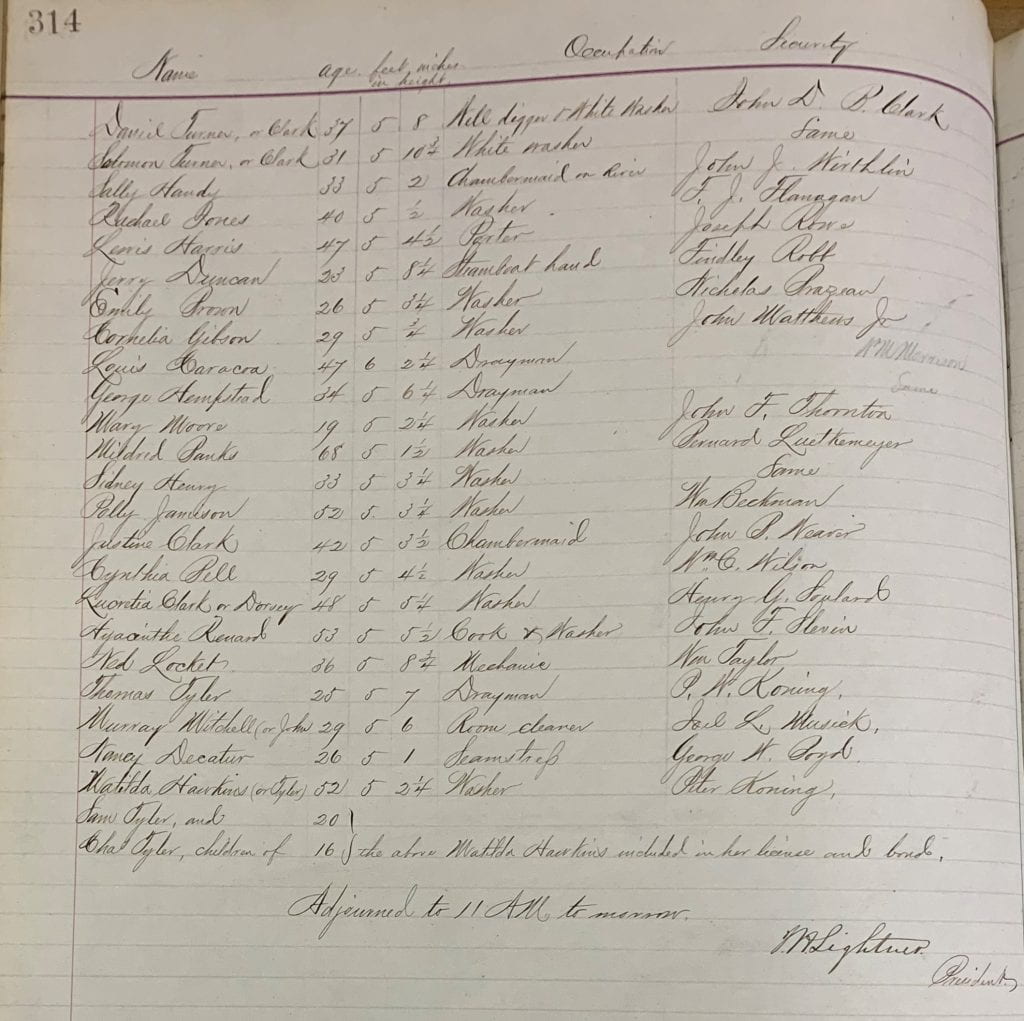

St. Louis County Court Record Book 10, April 17, 1861, p. 314, Missouri History Library.

About the record

On March 14, 1835, the Missouri General Assembly passed a law that required free Black residents to apply for licenses in order to remain in Missouri. Fearful of too large a free Black population, state legislators passed the law to limit the number of free Black people living in Missouri. If a free person of color was caught without a license they were arrested, imprisoned, and “brought up before the Board of County Commissioners, a panel of three judges who decided their fate.” Those caught were punished harshly. They were imprisoned, then either forced to pay a fine or lashed between ten and twenty times. If a person could not pay the fine in full, they were often hired out and forced to labor to pay it off. Finally, people found to be illegally residing within the state were forced to leave Missouri. In 1843, the General Assembly passed an even more restrictive act, “An Act more effectually to prevent free persons of color from entering into the State, and for other purposes.” Thereafter, free Black residents were forced not only to carry a freedom license, but also to pay an enormous fee, somewhere between $100 to $1,000, in order to remain in the state.

When Black St. Louisans applied for freedom licenses, the court’s approval or denial of their licenses were recorded in the St. Louis County Court Record Books. When approved, a copy of the license was given to the applicant and another copy kept by the court. Both records illuminate details about Black St. Louisans’ lives in freedom, but the purpose of recording and preserving these details about free Black St. Louisans was for surveillance. Information about a person’s occupation, address, physical characteristics, and relationships were recorded to allow Black residents to better be tracked down if they were caught without a license or apprehended in perceived violation of the terms of their freedom license. The white observer creating the record described physical characteristics and other identifying features based on what distinguishing features could be used to identify a person if caught. These descriptions, often focusing on racialized and exaggerated features, as well as marks of the violence of enslavement such as scars from beatings, were likely not how the applicants would have viewed themselves and one another.

Decisions regarding applications for freedom licenses recorded in the St. Louis County Court Record Books are different from the full licenses granted to free Black St. Louisans, and sometimes contain slightly differing information. See, for example, Matilda Hawkins, listed with her children at the end of the approval for freedom licenses in the image and transcription of the County Court Record Book above, compared to her freedom license below. The license, for example, has further descriptions such as the physical appearance of Matilda Hawkins and her children, which the County Court Book does not include in the data summarized about applicants.

“Know all Men by These Presents,

That we, Matilda Hawkins as principal, and Peter Koning as security, are held and firmly bound unto the State of Missouri, in the just and full sum of Five hundred Dollars, lawful money of the United States, for the payment of which we bind ourselves, our heirs,

executors and administrators, firmly by these presents, sealed with our seals, and dated this 17 day of Apl A.D. 1861

The condition of the above Obligation is such, that whereas, the said [Matilda Hawkins]

has applied to the Board of County Commissioners of St. Louis County for, and obtained a license to reside in the State of Missouri, during good behavior:

Now, if the said applicant shall be of good character and behavior during residence in the State of Missouri, then this obligation to be void, else of full force and virtue.

Matilda her X mark Hawkins L.S.

Peter Koning L.S.

Matilda Hawkins or Tylor aged 52 — 5′ 1/2″

Scar on left side of upper lip rather light

Children Sam Tyler 5’7″ aged 20 years straight hair like an Indian

Chas Tyler 5.5. aged 16 Dark Mulatto.”

The Washington University in St. Louis University Libraries Digital Gateway contains many digitized Freedom Licenses (See Matilda Hawkins’s here). The original records are at the Missouri History Library.

Freedom license records do not document every free Black resident of St. Louis from 1835-1863. Although all free Black residents of St. Louis were legally required to obtain a freedom license, not all did or were able to get a license for a variety of reasons, including not being able to prove having met the conditions for a license, not having a security, prohibitive cost, or possibly moral objection. Circumstances that threatened their ability to live freely in the state intermittently put pressure on Black residents living without a license, leading to surges in which many applicants sought freedom licenses during especially fraught and violent moments in the state’s history. Such a surge occurred after April 14, 1861, when the firing on Fort Sumter that precipitated the Civil War escalated political movement in St. Louis as citizens formed pro-union and pro-secession organizations. Pro-slavery actors in the Missouri State Assembly quickly replaced the St. Louis Police Force with their own Police Board, which threatened to arrest and prosecute any Black person in St. Louis who did not hold a license. In response, 404 Black residents of Missouri rushed to acquire freedom licenses between April 15 and June 3, 1861. Matilda Hawkins and her family were part of this group. Although Matilda Hawkins freed herself and her son Charles in 1848 (you can find their emancipation on the SLIDE database), and her other sons obtained their freedom in 1859, they did not obtain licenses until April 1861.

To learn more about St. Louis freedom licenses, see the report “Freedom Licenses in St. Louis City and County: 1835-1865,” by Ebony Jenkins.

About the database

The Freedom License Database, compiled through the National Park Service in the summer of 2008 by Bob Moore and Ebony Jenkins from the St. Louis County Court Record books, includes information about 1,493 people who successfully applied for freedom licenses in greater St. Louis. This information tends to include the name, sex, age, height, occupation, and notes on personal appearance of the applicant, as well as the name of individual who secured their application, the bond price, and the application date. Occasionally important details such as addresses and familial relations are included in this information. This database also includes the names of the 511 people with recorded court-mandated punishments for being caught without a freedom license, 50 cases in which people were denied freedom licenses, and a list of 80 related court cases.

Limitations

- Due to difficulties in reading 19th-century handwriting, there are some transcription errors in the database.

- The database contains freedom license applications in St. Louis County Court Record books, but not details from the actual freedom licenses themselves.

The SLIDE dataset

We have taken the Freedom Licenses database compiled by Bob Moore and Ebony Jenkins through the National Park Service, restructured some of its categories (columns), and cleaned the data within it for a higher level of searchability. We have begun correcting some transcription errors within the database, but have not yet completed this process.

Along with presenting the original transcription of people’s occupations listed in freedom licenses, as well as a cleaned and standardized listing of these occupations to enhance searchability, the SLIDE database has an additional column using broader groupings of occupation types as defined by Enslaved.org. We added two groupings to Enslaved.org’s categories: “Public works” and “Laborer.” The “Public works” category encompasses firemen, city bell ringers, and gatekeepers. The category “Laborer” encompasses people who worked in factories, general laborers, and railroad hands.

The SLIDE database currently only contains the freedom license applications detailed in the National Park Service Freedom Licenses Database. We hope to incorporate the full freedom licenses themselves into SLIDE at a later date.

Cite this page

Kelly L. Schmidt and Cecilia Wright, “About the Freedom Licenses Database,” The Saint Louis Integrated Database of Enslavement, July 2022, https://sites.wustl.edu/enslavementstl/freedom-licenses-database/.