by Kelly L. Schmidt and Cecilia Wright. Last updated July 2022.

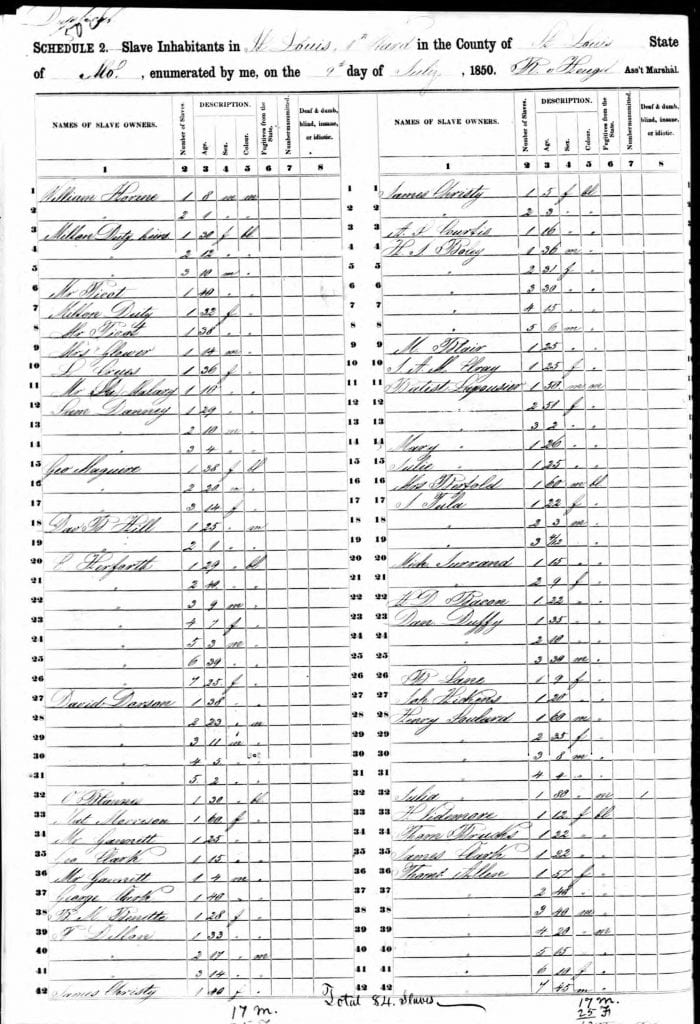

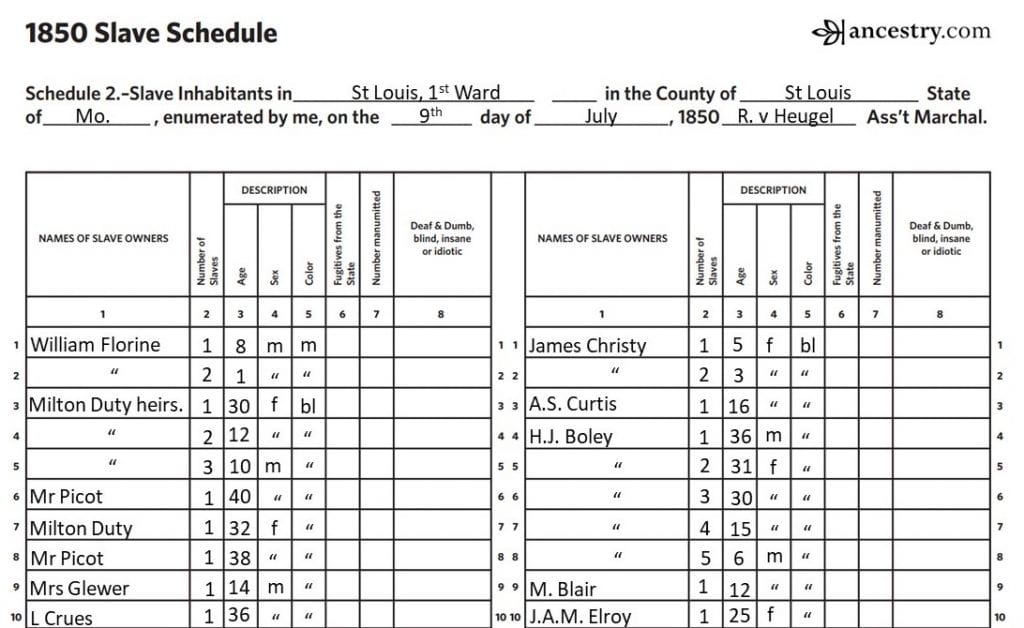

1850 United States Federal Census – Schedule 2, St. Louis Ward 1, St. Louis, Missouri, July 9, 1850, National Archives and Records Administration.

About the record

Prior to 1850, people held in enslavement were counted, unnamed, within the size of the household which enslaved them, along with the named head of household and, when applicable, dependents, boarders, and servants. The tabulation of the 1850 census (shown in the image and partial transcription above) marked a radical shift from previous censuses for two reasons. First, it separated enslaved people from free people in the household (in Schedule 1), recording them instead in Schedule 2, commonly known as the “Slave Schedule.” Second, and even more significantly, while earlier censuses had grouped all enslaved people within a certain age range and sex together, the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules have separate enumerations of each enslaved person in the household of each enslaver, recording each person’s age, color, and sex as usually assumed by the white enslaver or census-taker.

David Thackery, author of Finding your African American Ancestors, describes the contents of the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules as follows: “Although free African Americans were enumerated by name in 1850 and 1860, slaves were consigned to special, far less informative, schedules in which they were listed anonymously under the names of their owners. The only personal information provided was usually that of age, gender, and racial identity (either black or mulatto). As in the free schedules, there was a column in which certain physical or mental infirmities could be noted. In some instances, the census takers noted an occupation, usually carpenter or blacksmith, in this column. Slaves aged 100 years or more were given special treatment; their names were noted, and sometimes a short biographical sketch was included. In at least one instance, that of 1860 Hampshire County, Virginia, the names of all slaves were included on the schedules, but this happy exception may be the only instance when the instructions were not followed.

Sometimes the listings for large slaveholdings appear to take the form of family groupings, but in most cases slaves are listed from eldest to youngest with no apparent effort to portray family structure. In any event, the slave schedules themselves almost never provide conclusive evidence for the presence of a specific slave in the household or plantation of a particular slaveowner. At best, a census slave schedule can provide supporting evidence for a hypothesis derived from other sources. Prior to 1850 there were no special slave schedules for the manuscript census, as slave data was recorded as part of the general population schedules. In these, only the heads of household were enumerated by name.”

The US Census is not an objective recording of facts but, like all public records, a highly selective and politically motivated accounting of what mattered to people in power. The 1850 and 1860 censuses only recorded information about enslaved people that enslavers and government officials found useful. For instance, the census reported legal status, whether an enslaved person had fled or been manumitted from the household, or classified the enslaved person as deaf, dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic. The census asked only for the enslaver’s name and omitted enslaved people’s names. The 1860 slave schedule added a column for the number of slave houses on the property.

The decision to exclude names of enslaved people from Schedule 2 of the census was a conscious one influenced by Southern senators in Congress. To learn more, we highly recommend reading David E. Paterson’s article, “The 1850 and 1860 Census, Schedule 2, Slave Inhabitants,” which extensively describes the congressional debate over the census and the deliberate decision-making to ignore the dignity and humanity of enslaved people by excluding their names. The article also shows why we can’t fully trust the Slave Schedules’ representations of enslaved people’s genders, ages, or even the dwellings in which they lived.

To read more about the functions of and motivations for these Census records, consult the following sources:

- Martha Hodes, “Fractions and Fictions in the United States Census of 1890,” in Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History, ed. Ann Laura Stoler (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 240-70.

- Margo J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (Yale University Press, 1988)

- Jennifer L. Hochschild and Brenna Marea Powell, “Racial Reorganization of the United States Census, 1850-1930: Mulattoes, Half-Breeds, Mixed Parentage, Hindoos, and the Mexican Race,” Studies in American Political Development 22 (2008)

About the dataset

The 1850 and 1860 censuses (scanned and roughly transcribed on the genealogy websites Family Search and Ancestry). PDF scans of the Slave Schedules are also available on the Missouri State Archives website.

Family Search and Ancestry.com organize the scans of census records as they were arranged by the United States Census Bureau. But the Missouri State Archives has noted a pattern in how the Census Bureau originally arranged the records that has created misleading discrepancies in the data: “It appears that the Census Bureau, before binding the 1860 census, attempted to put the records within a county in alphabetical order by township. This created problems in counties where the enumerator did not start each township on new pages.” This means that if there was a list of enslaved people associated with one enslaver that spanned two pages, and the enumerator started with a new township on the second page, that the list of enslaved people may have been split from one another by the page break and regrouped alphabetically with a different county, leaving the possibility that enumerations of enslaved people in a household where the census pages for a township begin or end are erroneous. This can mean that the wrong enslaved people can be associated with an enslaver. The Missouri State Archives has rearranged the scans of census records on their website to correct for this error and “match the original order created by the enumerators and not the Census Bureau arrangement. Counties without name continuation problems were left as they were arranged by the Census Bureau.”

The SLIDE dataset

SLIDE uses the transcriptions from Family Search to create the 1850 and 1860 census datasets for greater St. Louis. These transcriptions, even less reliable than Ancestry’s, have been reproduced in our dataset. Therefore, their errors are present as well. Efforts are underway to review the original record and make corrections to the dataset. Due to the way Family Search has transcribed the censuses, we are also missing the categories blind, deaf, and fugitive from the state, as well as the number of enslaved dwellings listed on each property in 1860. However, the names of enslaved people over age 100, which are listed in the 1860 census, have been added to our dataset.

We have also not yet corrected for mis-joins as described by the Missouri State Archives, so we may have erroneous associations of enslaved people with an enslaver or township.

Our dataset does not currently contain data from all households of free Black St. Louisans or white-headed households with free Black residents within them, who are named in Schedule.

Cite this page

Kelly L. Schmidt and Cecilia Wright, “About the 1850 and 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules,” The Saint Louis Integrated Database of Enslavement, July 2022, https://sites.wustl.edu/enslavementstl/1850-and-1860-us-census-slave-schedules/.