Our lab studies how sensory information about orientation and movement drives appropriate body movements to adjust posture.

Awake animals normally maintain a given orientation with respect to gravity. This feature of behavior is so fundamental that it’s ingrained in colloquial language: we refer to a failed business as going “belly up.”

Posture is intimately dependent on signals from the inner ear, but we understand very little about how that information is mapped onto motor outputs.

The zebrafish is a terrific organism for investigating major questions in vestibulospinal signaling.

What are the spinal targets of vestibulospinal neurons?

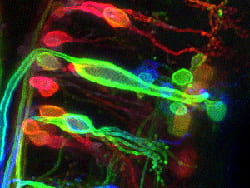

The spinal cord is home to a wealth of neuron types, which we can visualize and manipulate easily with transgenic zebrafish lines.

Posture is crucial to normal function: try walking when you’re lying on your back.

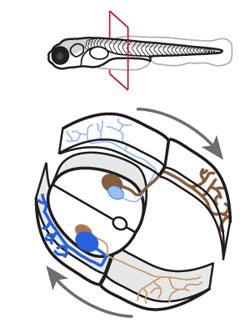

To understand how animals maintain posture, we study the vestibulospinal system of the larval zebrafish. Vestibular neurons in the brainstem report an animal’s movement and orientation with respect to gravity. A subset of them project to the spinal cord. What happens to the signals they carry?

How is sensory input functionally mapped onto the spinal output circuit?

Vestibulospinal neurons are tuned to all directions of head tilt. Logically, neurons with different sensory encoding should recruit different spinal populations, but because they are intermingled, no one has been able to investigate this.

Low neuron numbers and high accessibility in the zebrafish will let us tackle this problem.

How does locomotor feedback influence vestibular circuits?

Many vestibular neurons receive efference copy, but it is not known what circuits provide this feedback, nor how it develops and functions. We can watch development of cerebellar and spinal feedback to vestibular neurons over the course of a few days in the first week of life.