It is necessary to acknowledge that the year 2020 was inexplicably dense. Although my analysis may place these activism-oriented signs into conversation with Nato Thompson’s views on the artistic efficacy of didacticism and ambiguity, their interpretation is contextually fluid and should always be questioned. I cannot address the signs’ relationships to a myriad of relevant socio-political and pop-culture connections, but I hope to raise questions that will make you want to dig deeper into the culture these images reflect and reify. The views expressed in this essay are my own and are not representative of communities I address.

Key Terms

Ambiguous: that which encourages pluralistic interpretation and defies the obvious; “the poetic,

the absurd[…] the right not to be clear.”25

Didactic: that which is direct and/or obvious; clear intentionality; “the desire to teach and

moralize. This is often reduced to the notion that a work can be understood.”26

Sans Serif/Serif: in typography, smaller, ornamental strokes at the end of larger strokes are

known as serifs. (eg. Arial, or Helvetica are considered sans serif fonts, “sans” meaning

“without” in French. Serifs appear commonly in typefaces such as Times New Roman.)

Virtue-signaling: a preformative act that feigns representational betterment or allyship without

materially benefiting the communities they supposedly wish to aid.

Amidst a global pandemic and heated socio-political tensions, the year 2020 distended a nation, every nation. Americans were traumatized by racial injustices on their screens and in the streets. Churches all over the country took to their signage for addressing a variety of these complex and zealous dialogues, in-particular, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.[1]

St. Louis churches felt a particular moral responsibility to engage in this aesthetic dialogue as powerful public institutions within their communities.2 While a number of churches throughout St. Louis have since removed their anti-racist signage, some still stand. The act of removal demands many answers as to “why” and “when,” yet many more questions arise when we begin to interrogate why they exist in the first place. While these churches’ goals are presumably for community betterment, by what means did they go about consciousness-raising and what are the implications of such means? The various efforts of churches in St. Louis spurred a variety of questions, many of which I will not be able to unpack but hope you will consider while you read.

- What does it mean for a church to make a BLM or anti-racist sign after the summer of 2020?

- What does it mean for anti-racist signs to stand prominently, or not-so-prominently, in 2021?

- What does it mean to broadly reject racism without explicitly stating, “BLM?” – Are these signs a permanent reminder of or merely in the wake of exigent circumstances?

- Where within the churchyard do these signs appear?

- Does it make a difference whether the phrases are on their titular signage or elsewhere? – What does occupation of the church’s physical space enact conceptually? – Without a congregation physically present for most of 2020, who was making these decisions? – How does one go about representing an entire congregation?

- What personal and community biases are being integrated into these displays?

- Where in St. Louis do these signs appear most?

- What is the impact of the city’s redlining and subsequent segregation on where signs pop-up?

- Are these efforts merely virtue-signaling?3

- What kind of interventions from within the church are dismantling structural racism?

- Who is doing all the actual “standing” against racism? Or is it just the sign that is doing the standing?

I took to the streets in February and March of 2021 to see what visual remnants of 2020’s BLM surge continue to echo within these sites.4 Church signs across St. Louis utilize a number of visual means to signal their affiliation with the BLM movement, some more ambiguous,5 others more didactic.6 A sample of churches in Kirkwood (St. Louis, MO) provide an exemplar range of these methods. I first encountered the binary framework in Nato Thompson’s book, Seeing Power,7 where he unpacks the efficacy of these diametric qualities to provide a critical “spectrum of legibility” for socially-engaged artists.8 His discussion focuses on the powers this binary can employ and concludes with the understanding that “geopolitical, social, and site-specific context” is key to efficiently producing a “socially equitable landscape.”9 Both ambiguity and didacticism have their own strengths and weaknesses. The didactic’s desire to teach and provide clarity can often be read as naivete10, while ambiguity’s range of interpretations can provoke skepticism or worse, paranoia.11 A small sample of Kirkwood12 churches, walking distance from one another, provide a spectrum of didactic and ambiguous church signage that appeals to the divisive politics of racial justice.13

Erected in 2020, following the George Floyd protests, the sign made by Eliot Unitarian Church in Kirkwood is directly in response to surges of support for BLM in 2020. It features the movement’s iconic phrase in a metal and plastic frame alongside a notice for a weekly, silent vigil for BLM. A QR code attached links to their facebook page where information about the Church and vigil can be found. The vigils still occur weekly in April of 2021.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

At Eliot Unitarian Chapel (EUC) there is one of the most direct and grandiose signs I have seen in the whole city. It is much larger than the church’s titular sign on the corner of the property. Held up by a metal frame and posts, it sits directly in front of the entrance to the chapel, a prominent set of red doors. The sign reads, “BLACK LIVES MATTER,” in bold black and white (b/w) sans serif lettering,14 a nearly direct replication of the b/w BLM signs disseminated by the University City Action Network (UCAN) for their Black Lives Matter Yard Sign Project.15 These yard signs differ only in their serif font and ratio of the scale of text to frame. EUC’s larger sign, clearly hand-crafted, feels intimate while not attempting to mince words. The frame has even been laminated, weather-proofed for longevity. Alongside the framed BLM text, EUC’s graphic icon appears, abstractly-figurative of a lit altar. A smaller sign to the right of the framed displays in b/w, sans serif lettering, “VIRTUAL / VIGIL EVERY TUESDAY AT 5.” A QR code attached directs viewers to the church website where they can find links to attend the tuesday vigils and encourages community dialogue.16

Another sign on the site features a black graphic of a brushstroke-style heart over a yellow background. This sign, smaller than the first, occupies a wall of the church building to the right of the main display. Its message echoes the larger and more prominent one on the lawn, dually donning the BLM phrase in a high-contrast font. It also beckons the public to participate within the discussion.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

Another sign on the side of the church prompts and localizes the dialogue within the congregation. A rectangular, yellow banner states in black, sans serif type, “BLACK LIVES MATTER” and in smaller point-size beneath, “Join the discussion here.” To the left of the words sits a heart-shaped, brushstroke-style graphic. In tandem with the larger lawn display, these efficiently portray EUC’s welcoming intentionality and didactic resolve.

EUC’s signs are didactic at their core, attempting to “teach and moralize,”17 alongside minimal graphic fluff, the sign centers its BLM statement and even provides access to resources for further explanation and guidance. The weatherproofing and rigid structure of the sign greatly contribute to the work’s perceived sincerity. The potential for longevity authenticates the gravity of their attempt to counter systemic racism. Thompson notes the importance of intentionality to the efficacy of didacticism, by stating, “[…]the ability to read intentionality and the ability to teach are not exactly the same.[…]Increasing visual literacy provides an acute sense of intentionality.”18 Where intention can be discerned visually, this enables viewers to then question for themselves the intention, thus initiating a self-reflective process of observational learning. The hand-made quality, prominent scale, longevity, and call-to-action contribute to this work being perceptually intentional. EUC’s display doesn’t feel like virtue-signaling compared to the tragically tiny and ambiguously ineffective signs put up by other churches around the city.

Aside from socializing a path-of-least-resistance for their congregation to be engaged in a critical race dialogue, I still wonder if structural changes have been made to condemn systemic injustices within their community and clerical institution. I’m not so willing to step inside to find out and that limits my vantage point. The site-specific details are therefore limited to a formal exterior. Perhaps these textual displays are misrepresentative of their communities’ true intentions or maybe they are indicative of deeper unacknowledged truths behind the intent and lack thereof.

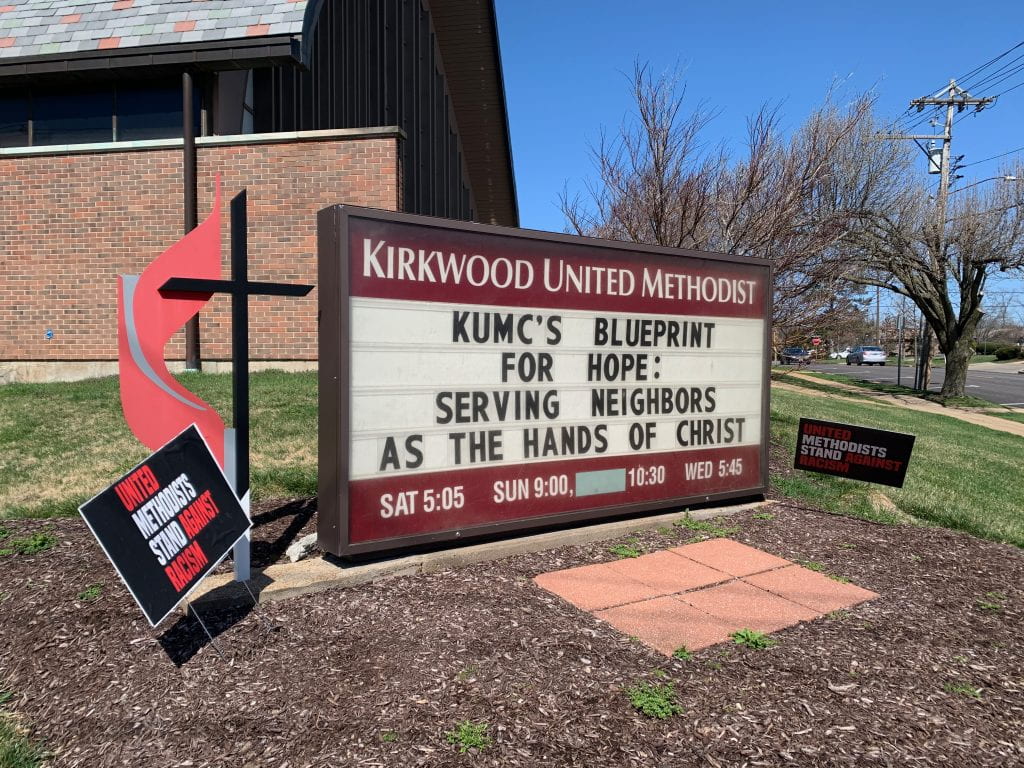

Erected following the George Floyd protests, the signs standing at the corner of Kirkwood United Methodist Church are an indirect response to anti-racist social movments such as Black Lives Matter. The signs in the Kirkwood location are much smaller than some of their counterparts across the city. Only up-close can one begin to discern the messages on the yard-signs. Yielding to gravity from their own weight, they are hardly legible from the road or side-walk.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

A few blocks over sits Kirkwood United Methodist (KUMC), whose signs walk a fine line of ambiguity and didacticism that, although perceptually limited, in some scales appears effective in communicating their anti-racist intentions. As one of many seed-churches within the St. Louis area, the denomination of United Methodists appears coordinated in their campaign.19 Their signs attempt to ambiguously refer to their position against systemic racial injustices, a direct response to the activist surge fueled by the 2020 BLM movement. However, their ambiguity feels detached and ingenuine. Due to the institutional/corporate aesthetics and deliberate omission of the words “Black Lives Matter,” their ambiguous gesture provokes skepticism.

A close-up of a water-worn yard-sign flanking KUMC’s larger, permanent sign announces their anti-racist position. Their support consists of flimsy metal wire. The only reference to the BLM movement is through the work’s visual style, and its timing following BLM protests across the nation.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

KUMC sits on a corner, using this public space in front of a massive chapel for its signage, a standard analog board with changeable letters for message flexibility. On either side of the sign sit two smaller yard signs with the message, “UNITED METHODISTS STAND AGAINST RACISM,” in white, sans serif type on a black background. The words “UNITED…AGAINST RACISM” are colored red, beckoning unity beyond the congregational label of “methodist.” The signs are illegible from the road and flimsy wire-frame supports hold the small yard signs at skewed angles preventing legibility from pedestrian and motorist passersby. They are even beginning to warp, presumably due to weather damage. The temporary construction negates their message’s potential for lasting commitment to anti-racist education, thus making their effort feel ephemerally ineffective. UMC locations in University City, and Jennings, differ greatly in their displays evidencing the choice local churches had in carrying out the wishes of the church bishops.

In contrast to KUMC, the sign outside Grace Methodist Church, facing thoroughfare Skinker Blvd. and bordering University City, is one of magnitude. It reads verbatim, textually and graphically, a replica of the yard signs outside KUMC; however, shifts in scale. It is made of weather-proofed canvas on a sidewalk-filling PVC frame.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

Grace Methodist Church (GMC) in University City used the same graphics as KMUC, additionally labeled with a URL for virtual accessibility and education.20 The sign at GMC is scaled-up massively, easily legible for motorists and pedestrians alike, and uses a PVC frame to support the mechanically-printed banner. GMC’s remained up until early March of 2021.

Outside North Park United Methodist Church, in Jennings, MO, there sits an educational yard-sign

providing practical measures for slowing the spread of COVID-19. Although, this site lacks visual media to spur anti-racist conversations, its placement within a largely black community lessens the need. It might feel redundant to encourage the conversation that’s already being had in those locales.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

North Park United Methodist Church (NPUMC), one of the few non-abandoned church buildings in North County, lacks a sign from the anti-racism campaign.21 Perhaps the largely black communities of North County do not need to proclaim the way white folx in the county might feel obligated. Only a small yard sign outlining measures for COVID-19 relief is up, its most prominent text reading, “HELP SAVE LIVES!” These locations’ exaggerations and negations respectively feel more intentional than the deteriorating and practically useless display in Kirkwood.

While still in direct response to the movement, these signs are evocative of skepticism due to the absence of the words “Black Lives Matter.” The campaign’s corporate persona is telling of the churches’ surface-level sympathy, but the fact that this is an institutionally vetted message feels impersonal and broadly reactionary, like a PR post to save face. At KUMC this is even moreso, due to the lack of apparent maintenance. Thompson notes the freedom ambiguity can provide as a form of escapism within an environment laden with visio-social manipulation. According to Thompson, “The ambiguous gesture can act, in many cases as a place of individual self-production, and as a way to escape the escalating war of coercive visual material.”22 The key to portraying effective intention is in the personality of the ambiguous. From an institutional perspective, the clean aesthetics and uniformity of the campaign feels impersonally manipulated and ultimately less genuine. Their widespread efforts appear, on the surface, to care for those affected by racial injustices and violence. So, I wonder, why are they whispering, “Black Lives Matter,” instead of shouting it?

St.Peter’s Catholic Church in Kirkwood features a two sign display, the larger constructed of metal, hearkening the value of life, and the smaller, a textual proclamation of their anti-racist stance. The site is quite far removed from the church building, instead situated on a corner flower bed on the church’s school property.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

Back in Kirkwood, St.Peter’s Catholic Church (SPCC), connected to a school of the saintly namesake, has posted anti-racist signage of their own. The display, much like KUMC’s, is a yard sign that hasn’t been properly adjusted in a while, illegibly angled towards the ground. It reads in small point, white and blue, sans serif type a number of virtues they, “STAND FOR” including, “LOVE, DIVERSITY,” and, “ACCEPTANCE,” before closing with the blanket statement in bold, “WE STAND AGAINST RACISM.” The sign sits underneath a larger metal one that reads, “RESPECT LIFE,” in a white sans serif font bordered by graphics of roses. Despite its placement alongside the smaller of the two, the larger sign doesn’t appear to address or have any connection to anti-racism. It presumably is an ambiguous reference to similar pro-life postings readily apparent on churches signs across St. Louis County.

Both signs use lighter fonts on a darker support. The larger display is arguably referential to pro-life sentiments, while the smaller provokes anti-racist and broadly inclusionary policies.

All photos by Mik McDonnell © 2021

This kind of display is a bandage-over-the-bullet-hole. Although textually didactic, the sign’s undeniable reference to the BLM movement, without direct, textual support is skeptically ambiguous. I question whether the words “Black Lives Matter” were too politically divisive and what powers were at play in the creation of a sign that broadly dispels racism. Overshadowed by a sign that directs us to “RESPECT LIFE,” the yard sign is an ineffective appeal for anti-racist sentiments. Situated underneath another incredibly didactic and to-the-point sign makes clear the lack of lasting intention or conviction in their statement. The anti-racist sign is blown over and neglected, unlike the official metal sign whose posture literally dominates the yard sign, leading viewers to visualize a conceptual hierarchy where racism is a secondary problem.

Thompson notes the effect of ambiguity is often achieved through the veiling of intentionality, saying, “In an ambiguous cultural intervention, the inability for a viewer to pindown a work’s intentions is the very thing that makes the dynamic significant.”23 SPCC’s sign’s textual didacticism undermines ambiguity by presenting a notion of pinned-down intentionally. In this way we understand the work not as an ambiguous reference to anti-racist activism but as an intentional ommitance of support for the BLM movement as a whole.

Throughout these St. Louis churches’ displays we can see a variety of didactic and ambiguous intentions reflective of the communities they reside within. However effective and/or ineffective as socio-political interventions, they are only a small sample of the St. Louis church community. Presumably erected in good faith, the intent to socialize anti-racism is a step in the right direction. Signage is also a necessary form of counter-speech to sentiments both opposing and supporting the BLM movement that have appeared on church signs across the nation. Yet again, maybe a lack of signage is more ambiguously effective than the preformative intentions assumed and exemplified by a poorly maintained and worded display. St. Louis’ history of geopolitical segregation, exemplified in the existence of the Delmar Divide,24 and as the birthplace of the BLM movement gives the church sites around the city a particularly important role in preserving our city’s history. At the end of the day, there will always be a lot to unpack within these signs, but I hope to see ambiguity used more effectively in support of the movement. Perhaps personally motivated works will yield more effective results that a public institution isn’t capable of sanctioning. It’s certainly possible in poetry and protest, we just need to continue to create differently, find new ways to tell our stories, and hopefully we will be ready to rally when these stories need to be heard.

Photo Gallery

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.2

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.2

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.2

Outside Oakville Community Church in Oakville, ON, and recorded on Twitter by user Hassan Naffaa

(@CodyComplex, July 13, 2020), sits a large display sign with interchangeable letters. The display reads, “WHITE PRIDE” in a bold, sans serif font. The sign also beckons visitors in with a smaller message underneath the first, noting, “Everyone Welcome.” The secondary message is ironically undermined by the exclusionary language of the first. Amidst national rioting in response to the continual killing of black folx at the hands of the police, this sign is an act of counter-speech by a white community who feels decentralized by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Figure 2

Signage outside the First Baptist Church of Bronston in Bronston, KY, has become a space site of political dialogue among the congregation and the community at large. Recorded on Twitter by user TexasNeanderthal.357 (@ASimplePatriot, Sep. 7, 2020) the sign has been visibly altered by an unauthored source. Over what once read, “UNBORN LIVES MATTER,” the word, “BLACK,” and “fixd ur sign” have been added in a revisionary, tongue-in-cheek fashion. The informal edit visualizes the community tensions surrounding the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement throughout summer 2020. The choice to appropriate the slogan and change it to a pro-life one, erases and subverts anti-racist rhetoric. Spray paint as medium also brings into question the role of ‘vandalism’ and materially antagonistic street art practices as measures of counterspeech for those without institutional supports or platforms.

Figure 3

Signage outside St.Mary’s Episcopal Church in Ardmore, PA, has been a site of contestation that has sparked congregational protests. Posted by user Vote them ALL out! (@roywlewis, Sept. 3, 2020), the tweet notes the sign has been “repeatedly vandalized” and is deteriorating, with duct-tape making up for lost sign. They also note the sign’s controversy spurred the congregation to arrive en-masse the day prior, Sept. 2, in support of the sign’s reconstruction. The sign itself sports the iconic message in bold, black and white lettering, “BLACK LIVES MATTER.” The sign, scarred by rips and tears yet standing strong, evidences sentiments of blackness historically represented by black protestors, embodying both societal vulnerability and unyielding endurance. The site’s visual accessibility and community backing have transformed the sign into a piece of their community’s history.

Figure 4

A sign in the lot outside Bradford Community Church Unitarian Universalist in Kenosha, WI, is consumed in flames, post-rioting, at the car lot next to the church property. Much like the posting user Jerry Oakley (@JERRYO1029, Aug. 26, 2020), many online critiques of the image targeted rioters as bringers of their own destruction. The sign itself, supported above flaming cars, reads in bold, interchangeable lettering, “BLACK LIVES MATTER.” The image of the sign, beginning to catch flame is certainly ominous and encourages viewers to weigh with gravity the environmental circumstances responsible for such devastation. While Twitter users like Oakley condemn the image as evidence of deviant behavior resulting in destruction of property, what is to be taken more into consideration: the unjust destruction of property or the unjust decimation of black lives, black bodies and black futures?

Figure 5

Digitally rendered signage, posted on Twitter by Little River UCC (@LRUCC, June 18, 2020) commemorates Juneteenth (June 19th) celebrations across the country with a digital banner reading, “BLACK LIVES MATTER,” in a white text, and “to GOD and to us,” in yellow text underneath. The sign is both celebratory, in-context, and socially relevant to the 2020 resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, taking advantage of their digital platforms to raise awareness. The addition of a theological argument to the slogan encourages viewers to question their spiritual connection to the movement. Although the digital formatting lacks personality, reminiscent of clean, corporate graphics, the speech act now occupies digital space to facilitate circulation.

Figure 6

Outside St.John’s Church across from the White House in D.C., the reverend, mayor, and his interfaith council gathered in support of the naming of Black Lives Matter Pl. Posted on Twitter by user MCCDC (@MCC_DC, June 5, 2020), photographs presented as a diptych situate a formally-dressed crowd in front of the church building as well as images of the updated street sign on a nearby lamppost/traffic signal. The crowd uses raised fists in a performance of solidarity for the Black Lives Matter movement as subsequent protesting occurred across the nation. The raised, black fist, iconically a symbol of the Black Panthers, has become synonymous with the BLM movement in 2020. The physical presence of protests is being enacted by both church and state officials to signal their support for the renaming. The renaming has been seen by some to be an extravagant example of virtue-signaling, that is, a preformative act that feigns representational betterment without materially benefiting the communities they supposedly aim to aid.

Sources

[1] “Black Lives Matter Yard Sign Project.” Black Lives Matter Yard Sign Project. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://blmyardsignsstl.org/.

“Crossing a St Louis Street That Divides Communities.” BBC News. Published March 14, 2012., https://www.bbc.com/news/av/magazine-17361995.

“City Of Kirkwood, MO.” Economic Development | City Of Kirkwood, MO. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.kirkwoodmo.org/business/economic-development.

“Delmar Divide.” St. Louis Public Radio. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://news.stlpublicradio.org/tags/delmar-divide.

“Herstory.” Black Lives Matter. September 07, 2019, https://blacklivesmatter.com/herstory/. River, Brick.

“United Methodist Bishops: Act Now to End Racism and White Supremacy.” Council of Bishops. June 08, 2020. https://www.unitedmethodistbishops.org/newsdetail/united-methodist-bishops-act-now-t end-racism-and-white-supremacy-14018643.

Schoenherr, Neil. “Environmental Racism in St. Louis: The Source: Washington University in St. Louis.” The Source. November 10, 2020, https://source.wustl.edu/2019/09/environmental-racism-in-st-louis/.

Thompson, Nato. Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the Age of Culture Production. New York: Melville House, 2015.

“United Methodists Stand Against Racism.” The United Methodist Church. Accessed April 21, 2021.https://www.umc.org/en/how-we-serve/advocating-for-justice/racial-justice/united-a gainst-racism.